Compromise is best course for Russia, EU in Protocol negotiations

RUSSIAN GAS TO EU MARKETS—Conclusion

When the energy ministers of European Union countries met in Thesaloniki, Greece, in February 2003, Turkey and Greece signed an agreement to build a 350-km gas pipeline to link the two countries.

Once completed, the mainline will provide yet another, southeastern route for gas supplies to Europe. More importantly, it would be an alternative to northeastern itineraries from Russia and Central Asian CIS nations. Two pipelines are already in place via Ukraine and Belarus and another one is planned to cross the Baltic Sea.

Supplies of both network gas and LNG to the European market from Norway, Algeria, and Nigeria are set to grow, and those from Britain and the Netherlands will likewise continue. The southeastern opening for imported gas to Europe is, therefore, going to make the already fairly stiff competition among its suppliers only more rigorous. Since each of these routes will have an extensive transit arm, only those suppliers who receive incremental competitive advantages will benefit in this further liberalized market. Those transit routes with existing available capacities for transit will be in demand under a "multiple-pipelines" concept of supplies, which will provide both producers, shippers, and consumers with fewer risks related to transit than other transit routes under consideration.

Under these conditions, Russia has two possibilities for increasing or preserving its presence on the European market:

1. Removing rivals "administratively," that is, by taking supplies of potential competitors, where possible, under its own control.

2. Providing additional competitive advantages for Russian gas by blunting or eliminating the existing competitive edge of other gas suppliers in Europe through various legal and economic means.

The Energy.Charter Transit Protocol aims to diminish tohose transit-related risks with the help of multilateral legally-binding agreement among the countries involved,i.e., by means of instruments of international law.

CIS gas via Russia to Europe

Russia's entering into a 25-year agreement with Turkmenistan last April on Turkmen gas supplies can be seen, inter alia, as the Russian answer to the decision by Greece and Turkey to establish the southeastern corridor for gas transportation from the east to Europe. This response was designed primarily to prevent Turkmen gas exports to Western Europe from escaping direct Russian control.

The response called for ensuring that export flows of Turkmen gas be directed into Russia to be put through Gazprom's system and thus ensure the latter of the possibility of exercising full-scale legal control over such deliveries. It was essential to make certain that once on Russian territory, they should be owned not by Turkmenistan but by Russia, represented by Gazprom.

This required that rather than coming to Russia in transit (in which case Russia would own title only to the pipelines, while Turkmenistan would itself continue to own such supplies), Turkmen gas should be purchased by Gazprom at least on the Russian border (under the two countries' agreement, it is actually bought on the Turkmen border).

Making this happen required offering adequate incentives (most notably, attractive purchasing prices from Gazprom and long-term guarantees of continued purchases of Turkmen gas in agreed amounts) to send supplies being pumped into Russian transportation systems over as many years as possible and thus remove the temptation for Turkmenistan's leadership to enter into similar agreements on alternative routes to deliver its gas to European and Asian markets.

Therefore, unlike those who argue that it is very difficult to answer the question of how the new agreement will benefit Russia economically, I believe that the answer is obvious: The benefits lie in precluding Turkmen gas transit (in the legal and economic meanings of the term) through Russia's territory.

Russia's leadership, including the captains of its gas industry, today view gas transit across Russian territory as a potential threat or an unavoidable evil but not as a potentially profitable line of gas business, which may be subject to transparent regulation for the mutual advantage of all participants. And it is the rules for such regulation that the negotiations on the Energy Charter Protocol on Transit are designed and seeking to produce. (For background on the Transit Protocol, see Oct. 20, 2003, p. 60.)

Implementing this scenario for getting rid of a competitor compelled the current Gazprom management and Russian leadership to substantially modify their policy vis-à-vis Turkmenistan when it comes to gas. Russia's newly won right to buy Turkmen gas appears, however, to be relative rather than absolute: The accord entitles both sides to review the terms and conditions of implementing contracts and abolish them 5 years after the agreement's execution.

This means that the Russian-Turkmen agreement is based on the so-called "right of first refusal," which provides for the possibility for both parties to review the material terms and conditions contracted (including prices and the volume of supplies), while granting Gazprom the preemptive right to purchase gas on new terms and conditions negotiated for the following 5-year period.

The threat of Kazakhstan searching for alternative paths (outside Russia's control) to bring its gas, primarily that from the Karachaganak gas condensate field, to the European market has been similarly deflected. The launch of the Russian-Kazakh KazRosGaz joint venture means that Karachaganak gas will be marketed in Europe after being processed at a factory in Orenburg, Russia, with Gazprom buying raw gas condensate from the joint venture on the Russian-Kazakh border to be able to control it as its owner along the entire subsequent chain of production and distribution operations.

Therefore, dry gas obtained at Orenburg from condensate derived in Kazakhstan is transported across Russia by means of its own pipelines (which belong to Gazprom) and exported to Europe as Russian gas (in the ownership of Gazprom).

Turkish syndrome

Having fended off, at least for the time being, the hazard of Turkmen and Kazakh gas supplies independently making their way to the European market, Russia and Gazprom, however, cannot in principle hope for any similar solution to similar threats from Azerbaijan and, even more importantly, from Iran and other Middle Eastern countries' gas, which will stream to Europe by the southeastern route.

All indications are that some of the gas produced in Russia itself, more precisely, a portion of Russian supplies to Turkey, may likewise go to Europe by the same route.

The algorithm of such (possible) re-exports appears to be as follows: The deceleration of projected economic growth in Turkey lately has made some of the previously contracted gas supplies to that country redundant and unnecessary for domestic consumption. Since export contracts are concluded on a "take-or-pay" basis, the country confronts the following dilemmas:

- Pressing for a review of the contracts already made to scale down supplies on a variety of pretexts (such as recent grievances over the quality of gas supplies from Iran); or,

- Reexporting an increasing surplus of contracted imported gas further on to Europe, which will require amending existing contracts to drop provisions on final designations (so called "destination clauses" in the existing long-term gas supply contracts), if any, and optimizing physical import flows by taking advantage of the country's latitudinal positioning.

A buildup of supplies from the southeast and northeast of Turkey (Iranian and Azerbaijani gas) may led to the need to reexport a portion of Russian gas coming in from the northwest (after crossing Romania and Bulgaria) "back" to Europe by the southeastern itinerary outside Russia's control (if the relevant Russian export contracts fail to include or have been reviewed to lift antireexport restrictions).

Turkey, it seems, has chosen the second option and has been fully entitled to do so as a sovereign nation. Significantly, with overflowing potential external sources of gas supplies, it also enjoys more room for maneuver than Russia, which must carry on full-scale gas supplies to Turkey, for example, by the Blue Stream gas pipeline for the investments in the project to pay off more quickly.

This means that Russia has only one possibility left to effectively augment its presence on the increasingly liberal European gas market keynoted by ever more aggressive competition: making Russian-produced gas supplies there more competitive.

International legal instruments have assumed ever-greater importance in this connection. These include the ECT and the Energy Charter Protocol on Transit (OGJ, Mar. 4, 2002, p. 20; OGJ, Oct. 20, 2003, p. 60), which is nearing completion and is especially important to non-EU gas suppliers to Europe.

At first glance, a mutually satisfactory outcome of the Transit Protocol negotiations now calls only for an answer to what is effectively the sole outstanding issue, that regarding the exercise of the right of first refusal on EU territory.

Two essential reservations should be made in discussing this problem:

1. When speaking about Gazprom in respect of current and (or) future gas exports from Russia, we will proceed on the assumption that for some time, the country will export gas through a single operator, say, Gazexport, regardless of whether the latter will continue to be a wholly owned subsidiary of Gazprom.

2. We will avoid indiscriminately using the term "Russian gas," which is usually understood to mean gas produced on Russian territory, because what is crucial for the purposes of this article and the Energy Charter Protocol on Transit (as will be demonstrated presently) is not the country of gas origin but the owner of title to gas produced in Russia on the territory of this or another country en route to its final user.

Russian gas in EU

The first in a series of consultations between Russian and EU delegations took place in Brussels Mar. 10-11, 2003. The consultations had been planned during the December 2002 session of the Energy Charter Conference as part of multilateral Energy Charter Transit Protocol negotiations in order to find mutually acceptable solutions to the remaining related outstanding issues.

During those discussions, the Russian delegation agreed—for the first time in the more than 3 years of talks— to the Transit Protocol including a Regional Economic Integration Organization (REIO) clause.

Under the REIO clause within the framework of obligations under the Transit Protocol, the term "transit" in respect of the REIO applies to energy flows crossing its entire territory.

The only REIO in the ECT context is the EU. This means that transit energy flows beyond the EU but within the expanding geographical space of the Energy Charter will be subject to the Transit Protocol's rules.

Today's energy flows within the expanding EU space are regarded as transit flows (when they pass through one or several EU countries but have another EU country as their final destination). These flows will no longer be treated as transit flows upon the approval of the REIO clause. The reason for this is that EU laws use the standard term "free movement of goods within the Community" and lay down uniform nondiscriminatory rules governing transportation, imports, exports, and transit.

Those energy flows will be subject to such rules as are spelled out by internal EU legislation.

The EU delegation during the March 2003 consultations took a serious step towards Russia. In response to the latter's basic consent to the addition of the REIO clause, the EU delegation suggested that Article 20 of the Transit Protocol (defining the term "transit" in respect of the REIO) be supplemented to include Clause 2, whereby the EU will undertake to grant national treatment to hydrocarbon flows originating outside the EU

This means that conditions for the transportation of foreign (read: "Russian") gas through the expanding territory of the EU may not be worse than the best of conditions for the transportation of gas from any EU country across the EU (say, the "transit" of Norwegian gas to Spain through France, or Dutch gas "imports" to Belgium, or "internal gas transportation" in Germany).

The EU, therefore, will agree to establish uniform conditions for the movement of any hydrocarbons (in terms of origins and title) within the expanding EU space.

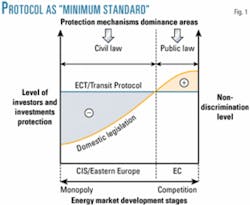

While in principle agreeing to this approach, the Russian delegation required that the Transit Protocol include a "minimum standard" provision to protect foreign gas suppliers on EU territory against extra institutional risks. Such risks and resulting additional transaction costs may be due to transition, upon entry onto EU territory, from a zone where shippers are protected by a range of civil-law remedies (as provided for by the Transit Protocol) to a zone where they are protected by public-law mechanisms (under EU legislation; Fig. 1).

In this zone, the EU legislation has been providing a higher level of non-discrimination for the shippers than domestic legislation in any other ECT state. Compared to Transit Protocol, however, that is done not by multilateral civil-law mechanisms, but by unilateral public-law instruments.

The latter, from the Russian delegation point of view, establish some incremental risks that can diminish the above-mentioned benefits. Or, in another words, they can or might push downward the yellow line in Fig. 1 (non-discrimination level provided by EU legislation) in the right zone of this figure towards or even below the blue line (non-discrimination level provided by the Transit Protocol).

For its part, the EU delegation accepted, in principle, the possibility of adding this kind of provision to the Transit Protocol, as the "minimum standard" concept underlies work on any international agreements, which at all times set a "minimum standard" for the parties' conduct in conditions reflecting the development stage of these or other markets in evidence at the time of the relevant negotiations.

The Transit Protocol is no exception and institutionalizes a set of arrangements and mechanisms for protecting shippers' interests, which is the same for all ECT countries, as a "minimum standard." This is the usual practice in enforcing the "balance of interests" principle in respect of nations finding themselves at different development stages: leveling is always based on some interim option.

'Minimum standard'; RFR

The possibility of including the "minimum standard" provision in the Transit Protocol and thus resolving the issue of the REIO clause's applicability, however, has run into a seemingly insurmountable obstacle: differences between the Russian and EU delegations on the exercise of the right of first refusal (RFR) on EU territory

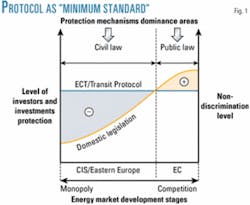

Here's how the two issues are related (Fig. 2).

The acceptance of the "minimum standard" requirement means that as far as each relevant Transit Protocol clause is concerned, the level of nondiscrimination and protection with respect to carriers, as ensured by EU laws, will be at least as high as provided for by the Transit Protocol itself.

Therefore, the "minimum standard" problem actually falls into the following two problems: the levels of protection and coverage zones under the Transit Protocol and those under EU legislation when it comes to issues with which the Transit Protocol deals.

Levels of protection. Reviews performed by both the EU and the Energy Charter Secretariat in 2002 demonstrated that safeguards for shippers, represented on EU territory by a triple-tier legal structure consisting of EU legislation proper, WTO rules, and the ECT, are at minimum the same as that protection accorded by the Transit Protocol (axis direction on Fig. 2).

Coverage zone. On the one hand, the coverage zone of EU laws on the transportation of energy materials and products is much wider than that of the Transit Protocol, because the former encompasses such operations left uncovered by the latter as internal transportation and imports and exports (abscissa direction on Fig. 2).

On the other hand, the range of issues covered by the Transit Protocol is broader than the scope of that EU legislation which is related to transit, as the latter does not provide for any right of first refusal.

The EU delegation to the negotiations has flatly refused to admit the applicability of RFR arrangements (see accompanying box) on EU territory, i.e., to introduce the RFR notion into internal EU legislation, arguing that this will contradict EU competition laws.

Therefore, the possibility of a denouement to the REIO clause problem hinges on a solution to that of RFR applicability on EU territory.

The need for the RFR surfaced following the break-up of the USSR, when internal transportation within the former Soviet Union and transit through the territories of friendly COMECON nations, then all but completely dependent on the USSR, were reduced almost overnight to what are now seen as transit flows of Russian energy resources across independent CIS and East European countries.

As a result, Russia, as represented by Gazprom, is interested in securing that the RFR applies in those countries through which Russian gas currently transits.

As already noted, "Russian" here represents the legal rather than the geographical meaning of the word. In other words, it points not to the origin of gas passing across the territory of this or another country (i.e., not to answer to the question of whence the gas comes) but to ownership rights in such gas originating and flowing in transit from Russia (i.e., to answer the question of who owns the gas).

Consequently, it is necessary to consider the ownership of title to gas produced in Russia during its supplies to EU territory, to determine in other words cases in which Gazprom is an incumbent transit carrier and, in particular, whether it has this status on EU territory today.

RFR on EU territory

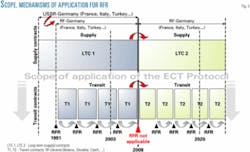

Fig. 4 shows principal (Ukrainian and Belarusian) routes used to export Russian-produced gas to the EU, highlighting several key points on these itineraries:

- "A" points on Russia's borders with CIS countries. There, title to the corresponding pipelines passes from Gazprom to companies in the respective CIS countries, but Gazprom retains ownership rights to the gas. It is also there that transit across such CIS countries commences.

- "B" points on the borders between CIS countries (the former Soviet frontier) and Eastern European nations (former COMECON members). There, title to the corresponding pipelines passes to companies in the respective Eastern European countries, but Gazprom retains ownership rights to the gas.

Also at those points, the latter's transit through the territories of CIS countries is replaced by transit across the corresponding Eastern European countries.

- "C" points on the transit Eastern European countries' borders with EU nations. It is there, on the EU outer boundaries that the Russian gas is sold to its Western European customers' companies in EU nations. It also there that the transit of the Russian gas through European countries ends and title to both the corresponding pipelines and to the gas itself passes to the respective Western European businesses or companies in EU nations.

During sales of Russian gas to France, for example, Gazprom sells through its foreign trade division, Gazexport, to Gaz de France on the outer boundary of the EU at Waidhaus on the Czech-German border.

Title to the gas there passes to Gaz de France, which then carries it in transit to France across Germany by means of pipelines owned jointly with the German Ruhrgaz. It is Gaz de France, not Gazprom, that acts as the "existing transit carrier" (the incumbent) in this case.

As far as I am aware, this also happens in all other sales of Russian gas to EU countries where the buyers are none of the "Zone IV" EU countries on the outer boundaries of the Community but "Zone V" countries within the EU, access to the territories of which requires that Russian gas supplies transit through "Zones II, III, and IV" (Fig. 5).

This means that there is no transit of Russian gas within the EU today, a conclusion that is key to the subsequent discussion.

If that is true (and the opposite has yet to be proven), the applicability of the RFR on EU territory will prevent Gazprom from penetrating more deeply into Europe—to "Zone V" countries such as France and Italy—and, in particular, to scale up supplies to consumers in the countries concerned, which have historically been (along with Germany) principal Western European markets for Russian-produced gas.

I have heard this conclusion dismissed as flawed on the grounds, for example, that there are some Russian gas supplies to Germany, including the former German Democratic Republic, whereby the gas goes further to other destinations in Europe and (or) that there are plans to supply Russian gas to Britain (as a result of Gazprom involvement in the Interconnector project).

Both these objections (and I have yet to hear any other) appear inadequate in reflecting the substance of an issue of fundamental importance in the context of the Transit Protocol. They are related either to supplies of gas deeply inside the EU that do not fall under the transit category (as they do not fit the definition of "Transit") or to suppliers owned by entities other than Gazprom.

In the event of gas supplies from Russia to the German domestic market (under agreements either between Gazprom and its shareholder, Ruhrgaz, or between Gazprom and its subsidiary, Wingaz), such gas on German territory is neither transit gas (Germany in this instance being the final destination) nor Russian gas.

Under agreements with Ruhrgaz, Gazprom sells gas on the German border terms, which is why the gas on German territory is owned not by Gazprom but by Ruhrgaz. Under agreements with Wingaz, ownership rights on the German border pass from Gazprom to the latter joint venture, the founders of which include the German Wintershall and the Russian gas monopoly (owner of a 35% equity in the joint venture).

Should the alliance of Wintershall and Gazprom buy a 26.6% shareholding in VNG, which controls gas sales in the former German Democratic Republic and is owned by Ruhrgaz and by E.On AG that has merged the latter, such gas on German territory will not be Russian either, even considering that a 15% stake in VNG today already belongs to Wintershall (the sale by July 31, 2003, of the shareholdings owned in VNG by Ruhrgaz (36.6%) and E.On (5.26%) being among the conditions on which the German government approved the two companies' merger).

Therefore, none of the three examples considered is that of Russian gas in transit (in legal terms) through Germany. Gazprom's efforts to get more deeply into Germany and gain access to German end users are not related to any transit of gas across German territory.

In the case with Gazprom's 10% equity participation in the Interconnector project (for gas supplies to and from Britain), gas transit in legal terms, presupposing the existence of physical flows through this or another country, is not at issue either. This is so because what is meant there, as far as I am aware, refers to swap transactions rather than any physical deliveries of Russian-produced gas to the UK, title to which will be retained by Gazprom throughout the entire route leading to the buyer.

Therefore, unless and until otherwise proven, the author will proceed on the assumption that the existing practice of Gazprom's exports of Russian-produced gas to the EU does not presuppose any transit of what is legally Russian gas within the community.

Consequently, insistence that the Transit Protocol include a requirement that the RFR be applicable to all ECT member countries will run counter to the interests of Russia and Gazprom itself if the RFR is applicable on the territories of EU countries as well.

Gazprom representatives to the negotiations have claimed, more than once, that their position on the need for the RFR to be invoked everywhere, including the EU, is strongly supported by all major Western companies, including Ruhrgaz, Gaz de France, ENI, and others.

Those companies' interests, however, and the interests of Gazprom regarding supplies of gas originating from Russia to the EU are diametrically opposed. They are opposed just as those of buyers and sellers ordinarily are, owing to wholesale prices on the border being twice as low as retail prices for end consumers within EU countries (with such prices, say, in Germany in 2002 standing, respectively, at $120 and $220/1,000 cu m).

Those Western companies have vested interests in continuing to buy gas from Gazprom on French-EU border terms so as to be able to resell it to end users themselves. Gazprom, for its part, should actually be interested in changing over from sales of its gas to these companies (acting as wholesale resellers) on the EU border to independently selling its gas directly to end European users.

The liberalization of the European gas market (and the EU Gas Directive) entitles gas end users in the EU themselves to choose their suppliers.

Its equity participation in Wingaz and (if it succeeds in efforts towards this end) in VNG means access for Gazprom to consumers in Germany, a "Zone IV" country (Fig. 5). This may be precluded, however, by the RFR being enforceable on EU territory, which will protect, for example, Gaz de France from Gazprom's penetration deep into the EU with independent gas supplies, while preventing Gazprom, as a new carrier, from accessing Available Capacity for the transportation of gas in transit on EU territory.

Therefore, claims of "unanimous support" in this case appear dubious, considering the opposite interests of the parties involved.

RFR, EU expansion

Fig. 5 demonstrates, however, that after May 1, 2004, when EU-15 turns into EU-25, the issue of RFR enforceability in the EU, or more precisely on the territories of the newly admitted EU members, will assume an entirely different tinge.

As an historically "existing transit carrier" on the territories of former COMECON countries, Gazprom will be interested in the RFR being applicable in the expanded EU.

This will mark a seemingly irresolvable contradiction, with Gazprom becoming simultaneously interested in the RFR being applicable and inapplicable on EU territory.

In fact, however, this contradiction is perfectly solvable, at least for as long as the existing long-term contracts on gas supplies to Europe continue in effect. There exist generally enforceable international-law provisions according to which, where EU laws applicable to newly admitted EU members after May 1, 2004, come into conflict with the provisions of earlier transit contracts, the latter are to prevail and to remain in full force and effect until expiry.

Article 5 of the Transit Protocol imposes the obligation to observe Transit Agreements and to refrain from their unilateral review. Therefore, following May 1, 2004, until the expiry of existing long-term gas supply contracts providing for the RFR, the provisions of such contracts will govern.

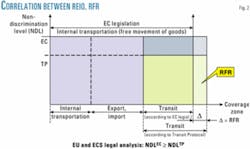

As the contracts are re-executed, they will no longer provide for any RFR (Fig. 3). By that time, gas markets both in Europe and in Russia will be differently configured, market liberalization processes will transcend the boundaries of today's EU, and it may well be that Gazprom's place, role, and interests on such markets will also be different.

It follows from this discussion that the mutually exclusive negotiating positions of the Russian and EU delegations on RFR applicability on EU territory may in fact be reduced to a mutually acceptable compromise.

If so, then it is in the interest of Gazprom and Russia overall to accept the EU proposal on the zone of RFR (nonenforceability).

In contrast, the possibility of invoking the RFR outside the EU—on the Asian segment of the gas market (for example, when purchasing Turkmen gas), obviously favors Gazprom, since by buying gas on the Turkmen border, it then becomes an "existing transit carrier" on the territories of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

The bottom line, therefore, is that outstanding issues relating to the ECT Protocol on Transit (in particular, to transit tariffs, the REIO clause, and the RFR) do have solutions mutually satisfactory to Russia and the EU and, consequently, the relevant negotiations may be completed successfully before long.

One question remaining is whether Russia and the EU are willing (and able) to conclude the Transit Protocol negotiations shortly in accordance with the corresponding decision of the December 2002 Energy Charter Conference or whether such a conclusion is prevented by reasons other than the problems related solely to the Transit Protocol.

During the most recent round of bilateral consultations between Russia and the EU on June 10, 2003, the delegations finally agreed on the compromise text of Transit Protocol. Now is the time to approve this preliminary agreement both in Moscow and in all the capitals of the EU member-states (both contracting parties did not manage to seek this approval before the Energy Charter Conference on June 26, 2003).

The time left until the next semi-annual Energy Charter Conference (Dec. 10, 2003) is limited.

Understandably enough, the Russian side is and will be seeking solutions to its existing differences with the EU in the ECT-related negotiating process as part of a systemic compromise regarding the full range of Moscow's relations with the European Communities and the simultaneous processes (unfolding at different paces and with differing measures of success) of accession to the WTO, the formation of a common European economic space, and Russia-EU energy dialogue.

Recent developments have demonstrated, at the same time, that Russia has been busy seeking with CIS countries, on bilateral and multilateral bases, mutually acceptable alternative solutions to problems associated with the transit of their energy resources across Russian territory.

But issues of internal reform required on the domestic gas market have as yet to be incarnated in specific government documents.

The mutually (for Russia and the EU) and multilaterally (for all 51 ECT member states) beneficial compromise text of the Transit Protocol is on the table. It appears that the issue of successfully completing the negotiations on the EC Energy Charter Protocol on Transit is now in the political court and waiting for a political decision of the two contracting parties.

About this series...

This is the second of two articles that address final issues to be resolved between the European Union and Russia en route to final agreement, scheduled for signing in a few weeks, on the Energy Charter Transit Protocol.

Under negotiation since early 2000 among 51 European and Asian governments, the Protocol aims to establish a clear set of inter-governmental "rules of the game," governing cross-border flows of energy in transit via pipelines and grids, and building on the existing transit-related provisions of the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty (OGJ, Mar. 4, 2002, p. 20).

Transit Protocol highlights

Under the draft Transit Protocol, "where the duration of Transit Agreements does not matchU the duration of supply contracts, a Contracting Party through whose territory Energy Materials and Products transitU shall ensure that the owners or operators of Energy Transport Facilities under their jurisdiction who are in negotiations on access to Available Capacity consider in good faith and under competitive conditions the renewal of such Transit AgreementsU. For the avoidance of doubt, it is understood that concerning conditions for access to Available Capacity the incumbent is treated no better and no worse than other potential users, and that such incumbent is first to be given an opportunity to accept the proposed renewal terms."

In other words, any new user of available capacity may only gain access to such facilities after an incumbent user decides against extending its existing transit agreement on the proposed renewal terms.

It follows that the RFR should only be invoked within the frameworks of existing supply agreements (in the event of supplies from Russia today, these include, as a rule, long-term export contracts on "take and/or pay" terms). The supply contracts themselves are not subject to legislative regulation by the Transit Protocol.

Therefore, the RFR does not extend to the re-execution of long-term supply contracts. But once this kind of contract is renewed, the RFR will under the new long-term export supply contract be applicable to access to available capacity for transit (Fig. 3 of the accompanying article).

Another important conclusion concerning the RFR is that Russia and its foreign trade gas monopoly, Gazprom, will be interested in the RFR being applicable on the territories of those countries where Gazprom is an "incumbent user of Available Capacity for Transit." Where Gazprom does not have this status, the applicability of the RFR will prevent Gazprom from obtaining access to available capacity for transit.