Thorny issues impede progress toward final Transit Protocol

The last session of the Energy Charter Conference in December 2002 marked progress towards completing negotiations, in their third year, among 51 European and Asian nations trying to hammer out a legally binding Transit Protocol to the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT).

All delegations to that round of the talks decided that the draft Transit Protocol had been agreed upon to an extent requiring no further negotiating, except for the following three related issues:

- The right of first refusal.

- The clause on a Regional Economic Integration Organization (REIO).

- The transit tariff-setting procedures.

Remaining snags

The purpose of the Transit Protocol is to provide a clear-cut set of multilateral international rules for the transit of energy resources and thereby to lower the level of political and financial risks associated with, among others, those oil and gas projects that require transit flows across Eurasia.

This will, for its part, make trans-border energy supplies on the emergent Eurasian energy market more secure and stable, diminish the cost of raising capital (equity and debt financing), increase the investment appeal of projects for the production and transportation of energy resources, and make them into more competitive options for consumers.

Therefore, the Transit Protocol, just as other legally binding documents relevant to the Energy Charter Treaty, is geared to ensuring not only the security and reliability of energy supplies, but also the consistency of demand by means of economic leverage. In other words, it is designed to benefit not only those consuming, but also those producing and supplying, energy resources.

The Transit Protocol will provide that minimum level of non-discrimination in the course of transit supplies that has been recognized as such by ECT nations.

Among other things, the Transit Protocol defines the term "available capacity" and includes provisions on methods to fix transit tariffs, on the granting of access for third parties to existing pipelines, and on the inadmissibility of any unauthorized "taking" of energy resources during their transit.

Following the attainment of final agreement on the remaining issues, the legal fine-tuning of its provisions, and its translation into all official ECT languages, the Energy Charter Conference will complete the Transit Protocol approval.

Before this happens, consultations have been conducted regarding those issues on which some delegations as yet have reservations. Final agreement remains elusive on ways to implement the REIO clause, included in the document on EU initiative, whereby the provisions of the Transit Protocol will not extend to the movement of energy resources within the EU, which will be subject to its own laws.

Conferring will also continue on the right of first refusal, wanted by Russia for transit energy suppliers, under which those having long-term supply contracts as well as short-term agreements on transit through third countries that are about to expire, will enjoy the priority right to be approached by the pipeline owner with a proposition to renew such agreements before the corresponding transit capacity is offered to other parties. The tentative consensus achieved on transit tariffs should be approved in the capitals of the respective countries.

In the course of multilateral negotiations and in the following December 2002 first round of bilateral consultations between the two, the EU delegation has continued to insist that the REIO clause remain in the Transit Protocol, which the Russian side has long viewed as undesirable. The Russian delegation, for its part, has persevered in its efforts for the Transit Protocol to provide for the right of first refusal, which in turn the EU, especially the European Commission Competition Directorate, has opposed.

In the course of latest consultations between the two, in June 2003, both contracting parties agreed in principle on what can be called (to borrow from chess) an "exchange of positions" in reaching a compromise. Their preliminary compromise must now be agreed within both capitals.

.The most difficult thing was to find additional arguments for the Russian delegation regarding the REIO clause. This clause, which is sometimes also called the "EU integration amendment," has remained for Russian the thorniest of the three issues yet to be agreed to by Moscow and the capitals of EU states in a final compromise agreement.

REIO clause

The integration processes under way in Europe have influenced the EU negotiating positions, prompting modifications of an economic nature, following political changes, for example, on transit problems.

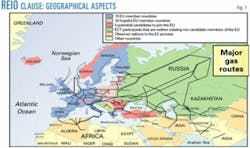

After the first 2 years of the negotiations, for instance, the EU proposed an article setting out an "integration amendment," which boiled down to requiring that for the purposes of transit, the territories of EU countries should be seen as together constituting an integral space, meaning that "transit" during supplies, say, from Russia to France should end on the outer boundary of the (expanding) European Community. That boundary is at present the eastern border of Germany and will later be the eastern border of Poland; Fig. 1 presents the "geographical aspect" of the problem.

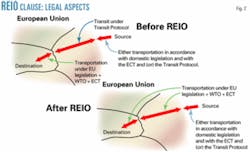

According to the EU's explanations and interpretation of its "integration amendment," the EU treatment of domestic operations to transport energy materials and products will be at least as favorable as, if not more advantageous than, that required under the Transit Protocol. This will be ensured by the internal legislation of the EU, which is based on the principles of non-discrimination and the free movement of goods within the Community, as well as by the legally binding obligations formalized by the WTO and ECT.

In accordance with a 1983 judgment of the EU High Court in Luxembourg, the treatment of freight movement across EU territory may not worsen with time.

The Energy Charter Secretariat, which also performed a legal review of the REIO clause, concluded that the triple-tier legal system—EU laws, WTO rules, and the ECT—will ensure that energy materials and products originating from one contracting country should enjoy treatment at least as favorable as that accorded to similar products from the EU (Fig. 2).

The EU confirmed that it goes along with the secretariat's conclusions. Furthermore, the Russian delegation also expressed its agreement with such views in the course of debates at the March 2002 round of Transit Protocol negotiations.

Russia, however, has since continued to insist (in, for example, its papers distributed in time for the June and October 2002 negotiating sessions) that "notwithstanding EU declarations on energy imports being treated at least as favorably as domestic energy materials and products and on existing and future EU legislation being consistent with the principles of non-discrimination and open, competitive markets,U Russia views the inclusion of the REIO clause in the Transit Protocol to be undesirable."

In the Russian side's opinion, the REIO clause "effectively excuses the EU of its obligations under the Transit Protocol,Uand agreeing to it would compel Russia to subordinate itself to existing EU legislation, as well as future EU legislation, as amended, of course, without Russia's participation, throughout the expanding territory of the Community, irrespective of whether this is to Russia's advantage or disadvantage" (June 2002).

In its comments prepared for the October 2002 round of the negotiations, the Russian delegation stated that "even today, EU legislative acts contain provisions which we see as unacceptable. These include, but are not limited to, the denial of a right of first refusal during the allocation of transit capacity and the establishment of transit tariffs by means of a mechanism for the distribution of resources in short supply, in other words, through auctions."

Considering that the parties in principle agreed on transit tariffs in December 2002, it was safe to assume that, should the EU accept the Russian side's persistent request that the Transit Protocol retain the provision on the right of first refusal, Moscow's objections to the REIO clause would, effectively and for the most part, be removed.

In its arguments against the "EU integration amendment" being included in the Transit Protocol, the Russian delegation stressed, as a rule, the geographical aspects of the problem, reasoning that the REIO clause ostensibly leaves 95% of Russian transit outside the frameworks of the Transit Protocol.

Such claims, I believe, were not quite correct, the more so as the most daunting problems faced by Russia in connection with transit operations are encountered en route to rather than in EU markets.

Under the REIO clause, no EU country signing the ECT as an REIO member treats supplies across any other EU country as transit, with transit only constituted by the movement of energy resources through the entire REIO territory.

Within ECT frameworks, the EU is the only REIO. Therefore, only the movement of energy materials and products across the entire EU is regarded as transit.

The Russian delegation routinely responds with the following example: Should the REIO clause be included, the only case of transit through EU territory will be Russian gas supplies to Switzerland (which today account for 0.4% of total Russian gas exports). Those supplies that will end within the EU will not be considered transit, even if crossing one or more countries grouped in the REIO, i.e., the EU.

If Russia supplies gas to, say, the Pyrenees, transit will be constituted by supplies from the Russian border to the outer boundary of the EU. With the EU being in the process of expansion (Fig. 1) and getting ever closer to the Russian frontiers, Russian negotiators argued, the result is that there is effectively no transit on EU territory and, hence, no need for the Transit Protocol, they have been saying.

Moscow does need the Transit Protocol, however, considering that, firstly, Russia experiences recurrent export problems with Ukraine and Belarus.

Secondly, the number of ECT observers is currently growing, primarily with the accession of Asian nations. The ECT member and observer-states "famiily" thus expanding to the south and southeast reflects natural development of energy markets in general and the Eurasian market in particular. So new problems with new transit operations are simply bound to occur there.

Therefore, the Transit Protocol retains its significance, although geographically, transit within an individual group of countries, as represented by the EU, is ceasing to exist as a legal notion, having been absorbed by the more general "free movement of goods."

The issue of possible additional transaction costs resulting from the changeover from "transit" (as regulated by the Transit Protocol) to "internal transportation" (as unilaterally regulated by EU countries), which was raised by the Russian delegation in June 2002 (but has never been suggested for further discussion at subsequent negotiations), is more important than the geographical aspects of the "EU integration amendment," which have been regularly pointed out as an example and are more obvious.

As a result, in the opinion of the Russian delegation, the approval of the REIO clause would entail extra export risks owing to transition from a sphere governed by civil law to that subject to public law (similar to switchovers from concessions or production-sharing agreements to licenses in the mineral extraction industry), and spell high export transaction costs.

It is not necessarily that transaction costs will increase should the REIO clause be approved. All contracting countries should satisfy themselves, however, whether this is indeed the case. Furthermore, negotiators during the October 2002 session of the Transit Working Group voiced a number of considerations that, I believe, make it possible for Russia to expect a number of positive effects from the approval of the "EU integration amendment."

EU integration

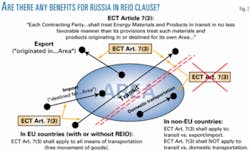

The possible advantage of the REIO clause for Moscow, it seems, may derive from Russia's not being obliged under Article 7(3) of the ECT, "Transit," to treat gas transiting through its territory on a par with that in domestic transportation because, unlike the EU, these operations are not legislatively subject to the same treatment.

This means, on the one hand, that one of Gazprom's objections to ratification of the ECT (namely, that the ECT amounts to an obligation to agree to the transit of Central Asian gas across Russian territory at the low or subsidized domestic transportation rates) is irrelevant.

This also means, on the other hand and perhaps more importantly, that Article 7(3) of the ECT will be applicable in EU countries, both following the approval of the REIO clause and (or) without it—to all types of transportation on EU territory, as EU laws use the term "free movement of goods."

At the same time, so as to determine that transit deliveries are not subject to discrimination, the self-same Article 7(3) of the ECT in non-EU countries will apply to the "transit-import/export" combination, while being inapplicable to the "transit-internal transportation" combination (Fig. 3).

In other words, according to the Transit Protocol, in countries outside the EU, the notion "internal transportation" is divided by a kind of "Chinese Wall" (double red dashed line on Fig. 3) from the notions "import," "export," and "transit."

How can the REIO clause benefit Russia in these conditions?

It will help in that Russian transit gas supplies across EU territory will be subject to treatment at least as favorable as the best of the three arrangements known, in Russian terminology, as "transit," "import/export," and "internal transportation," as all of them pursuant to EU laws are treated as "free movement of goods."

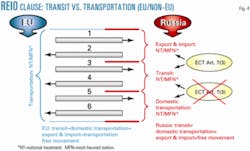

The "model" (benchmark) regime for transit will be the best of that applying to all types of transportation on the expanding territory of the EU. In contrast, transit deliveries of any foreign gas across Russian territory will not be subject to a similar requirement, as such transit supplies should be accorded such treatment as may not be worse than that offered for Russian imports or exports (Fig. 4).

This follows from a key provision of the 1958 Treaty of Rome which established the EU, on the free movement of goods in the territories of EU countries, whereby a sole (uniform) regime is applicable to all types of transportation of energy materials and products within the EU, including:

- Those originating from/heading for destinations outside the EU (exports).

- Originating outside/heading for destinations within the EU (imports).

- Originating and heading for destinations within the EU (internal transportation).

- Originating and heading for destinations within different EU countries (transit, prior to the implementation of the REIO clause).

Finally, the EU delegation has inserted this "national treatment" clause into its obligation into the draft article on REIO.

At the same time, outside the EU (Russia, for example), "transit," "internal transportation," "exports," and "imports" are operations that are not at all equivalent and do not all fall under "the free movement of goods" category, as each is subject to its own regulation (Fig. 4).

Therefore, the zone of non-discrimination against Russian gas on EU territory will be much larger than that of non-discrimination against any foreign gas on Russian territory. This is especially important considering that transit supplies through Russia should become, commercially, ever more significant for Gazprom and other (future) owners of gas transport systems, turning into an important independent line of gas business.

About this series...

This is the first of two articles that address final issues to be resolved between the European Union and Russia en route to final agreement, expected to be signed in a few weeks, on the Energy Charter Transit Protocol.

Under negotiation since early 2000 among 51 European and Asian governments, the Protocol aims to establish a clear set of inter-governmental "rules of the game," governing cross-border flows of energy in transit via pipelines and grids and building on the existing transit-related provisions of the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty (OGJ, Mar. 4, 2002, p. 20).

Energy Charter Transit Protocol

A legally binding agreement under international law, the Energy Charter Transit Protocol has been under negotiation since early 2000 among 51 European and Asian governments.

The decision to develop this agreement was made in recognition of the growing strategic importance of grid-bound energy transit in the Eurasian continent and the consequent need for governments collectively to reduce the economic and political risks associated with energy projects involving cross-border transit, particularly in the area of the former Soviet Union and countries that made up the former Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON).

The aim of the Protocol is to establish a clear set of inter-governmental "rules of the game" governing cross-border flows of energy in transit via pipelines and grids, building on the existing transit-related provisions of the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty (ECT).

Following are some of the Protocol's key features:

- Its definition of the concept of "available capacity for transit" in national pipeline and grid systems.

- The obligation it contains for signatory states to negotiate access to such "available capacity" in good faith and on a non-discriminatory basis with interested third parties

- Its establishment of the rule that transit tariffs must be non-discriminatory, cost-based, and free of distortions resulting from any abuse of a dominant market position by pipeline or grid owners.

The multilateral phase of negotiations on the Transit Protocol was completed in December 2002. Remaining differences in positions between contracting parties relate almost exclusively to Russia and the European Union. Negotiations on these positions have reached final stages, with only a few outstanding issues to be resolved befre its formal adoption, scheduled preliminarily for December 2003.

The issues—the European Union's proposal for a Regional Economic Integration (REIO) clause, the Russian proposal for a so-called "right of first refusal" for existing transit shippers, and the issue of methodology of transit tariffs calculations—comprise the subject of the accompanying article.

The Transit Protocol is key to achieving ratification of the ECT by Russia, which signed the treaty in 1994 but has yet to ratify it. Completion of this step (without which the ECT does not enjoy full legal force in Russia) is regarded by the European Union and other Energy Charter member-states as a major political priority.

The Russian Duma has declared completion of the Transit Protocol a condition for eventual Russian ratification of the treaty.

The author

Andrei A. Konoplyanik ([email protected]) is deputy secretary-general of the Energy Charter Secretariat, Brussels. In the late 1970s and through the 1980s, he researched international energy issues in the Institute of World Economy & Internatinal Relations, USSR Academy of Sciences (IMEMO), and in 1990-91 in the USSR State Planning Committee (Gosplan). He served as deputy minister of fuel and energy of Russia 1991-93 with particular responsibility for external economic relations and direct foreign investments. In mid-1990s, he worked as an executive director of the Russian Bank for Reconstruction and Development. From 1999 to early 2002, he was president of the Moscow-based Energy and Investment Policy and Project Financing Development Foundation (ENIP&PF). From 1993 to 2002, he also worked as a non-staff adviser ot several ministries in the Russian government and to the State Duma, where he headed the drafting group preparing legislation on production sharing agreements. Konoplyanik holds a PhD and a doctorate of science, both in international energy economics, from the Moscow-based State Academy of Management.