COMMENT: How to fix oil industry 'brain drain': Change the industry, not the image

A number of recent articles in industry publications have highlighted the maturing of the oil and gas workforce, quoting any number of statistics that highlight the impending retirement of the majority of those with experience in the oil field.

Frequently, these articles blame the lack of young people on the industry's image, inspiring the authors to close by calling for some sort of industry-wide public relations campaign to improve the image of the industry.

Unfortunately, this is a solution to the wrong problem.

Young professionals avoid the industry not because of its "image," but because of its "reality." The reality of the industry for young professionals is that it tells them:

- The majority of the workforce is twice your age; they're also almost all white males.

- You won't get to work on any really exciting technical challenges early in your career—those go to the "experienced" hands.

- You'll need at least 10 years of experience to be considered for any midlevel technical or managerial position.

- No one is going to go out of their way to share his knowledge with you. You're expected to learn by "putting in your time."

- You will be laid off—probably more than once.

Ignoring the demographics of the industry (which simply must change over time), these challenges may be broadly defined as "fascination with experience" and "lack of commitment to hands-on employee development."

Fascination with experience

Over the last 20 years, the oil and gas industry has eliminated an astounding number of jobs and has reduced new-graduate recruiting significantly.

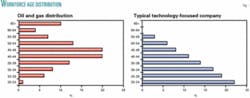

The results of these actions are demonstrated in Fig. 1. The graph on the left is the age distribution of the Society of Petroleum Engineers, here used as a proxy for the age distribution within an oil and gas firm.

On the right is a pyramidal age distribution representing other firms that recruit technical professionals such as conglomerates, high-technology firms, and consultancies.

Oil and gas companies have maintained a large bubble of personnel with 25 or more years of experience that hold not only senior managerial and technical jobs but also midlevel and even low-level positions. This glut has led to a culture that values experience over all else, that considers 10 years of experience a minimum, and that rewards staying in the same position for decades.

This focus on experience and the attendant lack of career velocity is both obvious and disappointing to young professionals.

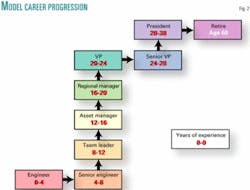

Like their peers in other industries, young oil and gas professionals expect significant technical challenges early in their careers. Furthermore, they expect their careers to progress every couple of years, allowing them early access to management or senior technical positions.

Young people expect to manage projects in their 20s, people in their 30s, and companies in their 40s. This is not arrogance; this is the reality of other industries.

Lack of employee development

The oil and gas industry's fascination with experience leads to another key challenge: Firms show little interest in employees until they have "put in their time." While many companies have rotational programs for new graduates, little effort is placed on career development once the rotational period is complete.

Some firms have experimented with formal mentorship programs, but these have quickly devolved into little more than lip service.

Instead, young professionals are expected to stay in a given position performing low-level tasks for 3-5 years. Then they are expected to move to a new group and repeat the process. There is no concerted effort to transfer knowledge from the veterans to the young professionals; they are expected to pick up knowledge experientially over time.

Furthermore, there is no effort to listen to the young professionals, to take advantage of their state-of-the-art education, their willingness to try new methods, and their fresh outlook. Not only is this inefficient, it is highly demotivating.

Young professionals interpret this disinterest in their development and their ideas as a lack of commitment on the part of the firm ("the company doesn't care about me").

This interpretation is reinforced by the industry's slow adoption of work vs. life balance initiatives and is driven home by the hire-and-fire mentality that pervades every public oil and gas company.

Three solutions from antiquity

While the problems the industry faces are real, they are not insurmountable.

Frankly, they are relatively easy to solve, assuming companies have the fortitude to try three solutions from the past: writing, apprenticeships, and contracts.

In combination, these solutions seek to transfer the knowledge of the veterans to the next generation, allowing oil and gas firms to give young professionals a rewarding and fast-paced career.

If firms are committed to creating the next generation of leaders, these efforts need to start today, as evidenced by a model career progression (Fig. 2).

Writing

Knowledge management often leads to images of enormous software installations and seven-figure bills from consultancies.

This need not be the case. Writing down what one knows, for the use of others, is an elegant way to help firms maintain the knowledge their employees have gained over multiple decades.

Many firms claim to do this already—through end-of-well reports, basin studies, or a number of other efforts. However, these efforts appear to be sporadic. True knowledge capture will require a more dedicated approach.

Firms should commit to a significant knowledge-capture effort, based on writing. Firms could select a portion of their veteran professionals to dedicate a significant amount of time to writing.

Their participation in the program should last for a year and should be considered an honor. The program would include additional pay and perks. Such a program might entail:

- "Knowledge days." Every Friday, these professionals would gather in a room to spend the day working on their reports. The work room must eliminate outside distractions—no cellular phones, pagers, or e-mail. The room should also encourage networking by including frequent breaks and catered meals.

- After a year of knowledge days, the veterans would attend a week-long "knowledge conference" to publicize the reports they have completed. Selected high-potential young professionals would be included in the conference.

- At the end of 1 year, the program participants would return to their standard duties, and a new class of veterans would be selected.

The details of report format, method of storage, and method of access would vary from company to company but need not be any more complicated than the establishment of a central library in paper or electronic form.

Apprenticeships

Once firms have begun to capture the knowledge of their veterans, they must transfer this knowledge to the next-generation workforce.

Again, an ancient method, the apprenticeship, is well-suited to the oil and gas industry.

An apprenticeship is a very simple process. A company pairs a junior employee with a senior veteran employee and makes it clear to the pair that the junior employee must be prepared for a midlevel position within a relatively short time frame, perhaps 3 years.

Naturally, successful completion of this training must be a key part of both individuals' performance evaluations.

Once the apprenticeship is complete, the junior employee must be placed in a midlevel position appropriate to his or her new level of knowledge.

There are several critical components of a successful apprenticeship:

- Both parties must be motivated and committed to the process.

- The junior employee must be placed in a senior position after the apprenticeship.

- Note that the junior employee should be placed based or his or her skills, rather than on experience.

Apprenticeships can be successful not only at the entry level, but also at much more senior levels.

For example, high-potential employees with 5-10 years of experience could train through apprenticeships for positions as asset managers, regional managers, or even vice-presidents.

Contracts

Once firms have initiated "knowledge days" and apprenticeships, they will be well on their way to building the next generation of leaders.

However, a significant hurdle will remain: trust. Young professionals will not trust that oil and gas firms are committed to these programs, to genuine career development, and to enhanced career velocity.

They will continue to hesitate when selecting an industry in which to build their careers.

Firms will need to demonstrate an extraordinary level of commitment to the next generation to become attractive workplaces.

One way to demonstrate this commitment is through employment contracts.

Firms should offer new and junior employees significant contracts—3 years, 5 years, or even 10 years. These contracts serve two purposes.

First, it demonstrates a very high level of commitment to young professionals, beginning the trust-building process.

Second, because each young professional now represents a significant expense, firms will be highly motivated to offer these employees early opportunities to add value to the company.

Changing reality

The majority of the oil and gas workforce is rapidly approaching retirement age, and the "reality" of the industry is not attractive to young professionals.

However, with a solid commitment and a few simple initiatives, the industry can change its "reality" into one that promises exciting development opportunities and challenges for employees at all levels, thus becoming a target industry for the next generation of business leaders.

Oil and gas companies must begin to capture the knowledge of their veterans.

They need to find the young professionals already in their ranks and place them in rapid-development apprenticeships to prepare them quickly for roles as asset managers, regional managers, and vice-presidents.

Firms must commit not only to developing young people for leadership, but also to giving them the opportunity for senior positions early in their careers.

Finally, firms must work to establish trust with the next generation of industry leaders.

The challenge is real; the crisis is here. The solution is simple, but it must begin today.

The author

Michael Minyard is employed by an undisclosed integrated oil and gas company in Houston. He has a BS in mechanical engineering from Rice University and an MBA from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.