Russia's new pipelines will debottleneck exports, production

Last year, Russia became the world's No.1 producer of crude oil (7.7 million b/d) and the world's second largest oil exporter (3.8 million b/d), having left behind all major oil suppliers, except Saudi Arabia.

The events of Sept. 11, 2001, emphasized Russia's potential role as a new alternative source of massive oil supplies, which seem politically more acceptable than those from the terrorism-prone Middle East. Does this widespread perception reflect the reality?

Can Russia really press Mideast oil exporters off the market or is it just wishful thinking of ignorant politicians? Surprisingly, answers to those questions lie in the further development of Russia's oil pipelines.

Mysterious oil exports

Before assessing Russia's new global role in displacing (or supplementing) oil exports, it seems expedient to clarify what we really mean by "Russian exports." Some think about Russian crude leaving the country (regardless of its final destination), others debate about total (Russian plus non-Russian) oil flows outside the former Soviet Union, while others talk exclusively about exports of Russian crude oil to the enigmatic "far abroad."

Understandably, it makes some difference.

In the heyday of Soviet oil exports (late 1980s), the "unbreakable union of Soviet republics" used to export up to 2.9 million b/d of crude, mostly of a special blend known as "Urals" (as it was mixed in the Volga-Urals region) or as the "Soviet export blend" (with around 32º API and 1.8% wf sulfur).

Urals flowed through the Druzhba (Friendship) pipeline to Eastern Europe as well as via the Soviet oil ports on the Black Sea (Novorossiysk, Odessa, and Tuapse) and on the Baltic Sea (Ventspils). Some other minor crude oil streams ran to foreign destinations by rail, mainly to China and via seaports in the Russian Far East.

After the USSR breakup in late 1990, Russia lost sovereign control over pipeline outlets to Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary as well as over Ukraine's port of Odessa and Latvia's Ventspils. But the Russian oil pipeline monopoly Transneft continued to control crude oil flows through all those outlets as the export pipelines were fed chiefly by Urals (now dubbed "Rebco," Russian export blend crude oil).

After awhile, other ex-Soviet republics (like Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Belarus) started to use the Transneft-controlled pipelines for exporting their own crudes and to build new pipelines (the CPC line from Kazakhstan to the Black Sea, for example) and terminals (such as Butinge on Lithuania's coast of the Baltic Sea) to facilitate their own oil exports or to serve those from Russia.

As a result, the formerly indivisible Soviet exports of crude oil (all going outside the USSR) were broken into three main streams:

1. Russian crude export to outside the former Soviet Union (FSU).

2. Russian crude supplies inside the FSU (mostly to Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan).

3. Non-Russian crude flows (chiefly from Central Asia, Azerbaijan, and Belarus) through Transneft-controlled network to non-FSU destinations as well as to other ex-Soviet republics.

Although Transneft distinguishes its oil shipments to within and outside the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), with the Baltic ex-Soviet republics being regarded as "outside" or "far-abroad," a Western observer is accustomed to reckon how much crude is exported by Russia (and other post-Soviet countries) beyond the borders of the FSU.

Mirroring overseas demand

Initially, after the USSR breakup, Russia's crude exports to non-FSU destinations were severely impeded by the marketing terms of new, commercial contracts, which the former Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe had to accept. The much weaker and virtually insolvent ex-Soviet economies, however, were affected to a far greater extent and could now afford only a modest fraction of their former imports of Russian crude (Fig. 1).

Consequently, total exports of Russian crude oil shrank to less than 2.5 million b/d in 1995 from 3.5 million b/d in 1991, with Russia's supplies to other ex-Soviet republics nosediving to 0.6 million b/d from 2.4 million b/d and even farther later. The drops had nothing to do with the notorious depletion of Russia's oil reserves; the market-priced Russian oil had simply lost its formerly subsidized ex-Soviet buyers.

As for the better-off hard-currency buyers outside the FSU, the initially depressed demand for Russian crude has been steadily recovering and by now has exceeded its previous, 1988 record level of 2.9 million b/d. In the late 1980s, however, it was related entirely to Soviet exports, which now should be compared with non-FSU supplies from and through Russia, that is, with regard to crude oil transit by other ex-Soviet states, which is likely to top 0.7 million b/d this year (Table 1).

No doubt the exports could have been growing even faster as, since 1993, the Russian domestic oil market has been suffering from persistent over-production. Russian oil companies could have built up much-desired hard currency exports to much higher levels, had it not been for the existing export bottlenecks.

Stretching to the limit

It is worth noting that today Russia's annual oil balances, including oil production, stem from the nation's critical dependence upon oil export revenues. These oil exports constitute the only reliable source of the cash that is badly needed to pay Russian oil companies' wages, taxes, and bank loans.

Moreover, although not as important as in most OPEC countries, oil related hard-currency revenues serve as revitalizing "shots in the arm" of the still unstable national economy.

During the last years, together with oil product sales, exports of crude oil accounted for around a third of the country's export revenues. Even more important, the oil sector makes up about 15% of Russia's GDP, while oil-related taxes secure up to a quarter of the federal budget receipts.

In other words, Moscow cannot afford to sacrifice any part of those revenues for the sake of supporting world oil prices.

Hence, under any circumstances, Russia would export as much oil as it can. The country's ability to export its crude oil, however, is limited by available export facilities.

In particular, last year, major export capacities (of pipelines and sea ports) potentially available for Russian crude exceeded 4 million b/d. This technical potential was used in 2002 for only 2.5 million b/d, with some spare capacity conceded to Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Belarus under intergovernment agreements.

Still, with more and more export facilities being gradually commissioned in the years to come, Russia will enjoy greater export capacity for its crude oil.

Export projects

In Russia's oil sector today, one can hardly find any major infrastructure project that is not directly aimed at increasing oil exports. Despite officially declared export cuts, the country continues to boost its crude supplies by quickly debottlenecking existing and building up new export outlets—in the West, Far North, and Far East.

At Russia's western approaches, the Druzhba pipeline remains the main oil export artery for Russian crude, capable of handling up to 1.3 million b/d. Its northern branch, with capacity of about 0.9 million b/d, feeds Poland and Germany; its southern branch, with capacity of 0.4 million b/d, exports to Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and the former Yugoslavia.

Because of shrinking oil demand in Eastern Europe, however, the pipeline is now substantially underutilized. Last year, Druzhba's capacities were utilized at an average of 80%, with its southern leg loaded for only 75% of its nameplate capacity.

Use of this southern capacity should be enhanced when the 35-in. Adria pipeline, from the port of Omisalj (Croatia), has been reversed to ship Russian crude to the Adriatic (Fig. 2). The scheme, proposed by Yukos and backed by Tyumen Oil Co. (TNK), aims at 100,000 b/d in 2004 and up to 300,000 b/d by 2010.

The reversal phase of the project looks quite cheap ($20-30 million), while the earmarked extension to 300,000 b/d will require up to $320 million of estimated capital investment.

Originally, Croatian pipeline operator Jadranski Naftovod dd (Janaf), Zagreb, was supposed to complete reversing its section of the Adria pipeline by the end of this year. But the company cannot start the work before it has received approval from Croatia's environment ministry, which is worried about the effect of ballast water disposal on the Adriatic's marine life.

As a result, the 100,000-b/d phase of the Druzhba-Adria scheme is not now expected to become operational before mid-2004. Besides, implementing safety and environmental requirements is likely to add around $60 million to the project's estimated outlay.

In August 2001, the Druzhba's Ukrainian section was linked by the Odessa-Brody pipeline to a new oil terminal at Pivdenne (or Yuzhny), built some 25 miles northeast of Odessa (Fig. 3). The 420 mile, 40-in. line, with its current capacity of 180,000 b/d, can be expanded up to 500,000 b/d (and even 900,000 b/d) and extended by 190 miles to Polish refinery at Plock.

The Brody-Plotsk extension would require 2-3 years and between $300 million and $500 million to build—in addition to the more than $160 million already invested in Odessa-Brody. The plan is vigorously supported by Kiev as well as by Warsaw, Berlin, and the European Union, none of which, however, would provide the needed money.

Anyway, the extension can materialize only when (and if) UkrTransNafta, which runs the still idle Odessa-Brody line, finds desperately sought-for oil supplies from the Caspian to ship crude from the Black Sea to Plock and further via the Pomeranian pipeline to the Baltic port of Gdansk.

This July, 2 years after the ill-fated Odessa-Brody was built, the first signs of formal interest in using it have been shown by Kazakh state oil and gas holding KazMunaiGaz (KMG), which has pledged to conduct a feasibility study of extending the line to Plock with the aim of shipping up to 160,000 b/d of Kazakh crude via Pivdenne to the north.

In the meantime, Russian oil majors (including Lukoil, Yukos, and lately TNK) seek to persuade the Ukrainian government to save the unfortunate project by reversing the Odessa-Brody line to pump Russian crude through the Pivdenne terminal for seaborne exports.

The Russian oil companies, actively backed by Moscow officials, would like to use a part of the current 240,000- b/d excess capacity in the Druzhba pipeline system to ship their crude southward across Ukrainian territory. Their desire for additional oil exports seems to justify a relatively high tariff for the line of $4.30/ton ($0.60/bbl) plus an additional fee from the Belarus border to Brody of $2.30/ton ($0.30/bbl).

Since the start of 2003, a short (32 mile) southern fragment of the pipeline between Michurinsk and the 840,000-b/d (nameplate) Pivdenne terminal have been used in reverse by Russia's TNK and recently by a Gazprom-linked trader TransNafta and Bashneft (a large oil producer from the Russian republic of Bashkortostan).

In late August, under ever-increasing pressure from Moscow, which has manifestly curtailed its crude exports via Odessa, Kiev agreed to allow Russian companies to use the Pivdenne outlet for up to 80,000 b/d of their crude, starting from fourth quarter 2003. Most analysts believe this may signify the looming end of Kiev's desperate resistance to the reverse use of the Odessa-Brody pipeline.

This export route also attracts Kazakh exporters, which cloak their vital interest by talking the Plock extension (see previously). In late July, KazMunaiGaz succeeded in convincing UkrTransNafta of the need to lay a parallel 32-mile Michurinsk-Pivdenne line for shipping Kazakh and Russian crudes.

Kazakhstan has also offered to build a new berth at the terminal to handle its crudes. According to KMG, this would keep the Odessa-Brody line free for its original mission—to pump oil northwardUbut whose oil?

Polish pipeline operator Pern plans to invest around $200 million to increase the flow of Russian crude to the Naftoport oil export terminal in Gdansk.

Currently, the terminal is running at only a fraction of its capacity because of the Druzhba pipeline restraints. Most of the earmarked money will be spent on construction of a new line along the northern branch of the Druzhba pipeline from the Belarus border to Plock, which will connect with Gdansk by the Pomeranian pipeline. The 145-mile Adamowo-Plock line, which would boost capacity of the Druzhba's northern leg to nearly 1.3 million b/d from the current 880,000 b/d, can be completed by 2006 (Fig. 2).

Another opportunity for Russian exports is partial use of the IKL pipeline, which connects Germany's Ingolstadt refinery with Czech refineries at Kralupy and Litvinov. IKL's operator Mero CR AS proposed to use half of its 200,000-b/d capacity in reverse, to pump up to 100,000 b/d of Russian crude to western Germany, instead of using the line to feed the Czech refineries with Mediterranean crudes. Russia's Yukos is interested in the proposed scheme but must persuade Czech and German refiners to switch over.

After acquiring a 49% stake in Slovak pipeline operator Transpetrol in late 2001, Yukos expressed its interest in building the Bratislava-Schwechat link pipeline. The 37-mile line would connect the 115,000-b/d Bratislava refinery in Slovakia with OMV AG of Austria's 180,000-b/d Schwechat refinery near Vienna, currently being supplied via pipeline from Italy's port of Trieste.

This August, Yukos and OMV agreed to set up a joint firm, which would build the link pipeline with initial capacity of 72,000 b/d, potentially rising to 100,000 b/d. To keep the $30-million line busy, Yukos pledged to supply OMV's refinery with up to 100,000 b/d of Urals crude for an initial period of 10 years, starting at 40,000 b/d in January 2006.

The Austrian company was expected to own 24% of the new firm, with the remaining 76% going to Yukos. The latter's share is now likely to be lowered, however, to accommodate Transneft, which has been invited to join the venture.

The Russian pipeline monopoly was known to be interested in the Bratislava-Schwechat link and has been proposing to extend it further to Virye, Croatia, where it would join the Adria pipeline. Now that the Druzhba-Adria project has taken off, however, the proposed $200-million Schwechat-Virye extension looks redundant.

Western seaports

On the Baltic front (Fig. 4), the Latvian port of Ventspils remained the main outlet for Russian (and Soviet) crude destined for northern European markets until it was recently embargoed by Russia's oil pipeline monopoly Transneft, seeking to buy a controlling stake in the port. If Transneft succeeds (with a sell-or-die ultimatum expiring by May 2004), the current 320,000-b/d capacity of the now-idle outlet can be expanded to 360,000 b/d.

As an alternative to the independent Ventspils, Transneft in late 2001 built its own Baltic terminal at Primorsk, on the Gulf of Finland, northwest of St. Petersburg. Its fully used original capacity of 240,000 b/d was increased to 360,000 b/d in early July 2003 and is earmarked to rise to 600,000 b/d by the start of 2004 and 840,000 b/d by May 2004, at the latest.

Ultimately, capacity can reach 1.14 million b/d, although it depends on market conditions, in particular, on future oil exports from Iraq.

The first phase of this Baltic Pipeline System (BPS), which included a new 40 in., 240,000-b/d pipeline from the Kirishi refinery to Primorsk, cost Transneft some $600 million (or $140 million more than initially planned). The ongoing, second phase, which will boost BPS capacity to 840,000 b/d and envisions construction of a new but longer 40 in., 600,000-b/d line from Palkino (near Yaroslavl), is estimated to cost $1.2-1.4 billion.

Also, if fairly heavy ice conditions of Primorsk keep undermining economics of using this expanding export outlet, Transneft has a standby plan to build a160,000-b/d pipeline from Primorsk to Finland's more easily accessible port of Porvoo.

With a recent takeover of Lithuania's Mazeikiu Nafta by Yukos (OGJ Online, Apr. 28, 2003), the Lithuanian port of Butinge, which was built in mid-1999 to feed the starving Mazeikiu refinery, has also become available for Russian crude oil exports. Moreover, the Lithuanian government has recently proposed to expand the port's current capacity of 160,000 b/d to around 250,000 b/d. And Yukos has responded with a plan to finance its expansion to 280,000 b/d.

Finally, Russia's oil export capacities in the Baltic will be boosted by developing Lukoil's new terminal at Vysotsk. The first 50,000-b/d phase of the projected 220,000-b/d export terminal, which is being built 18 miles north of Primorsk, is to be completed by yearend, with about 140,000 b/d expected on stream by 2005.

Although the $300-million project is mostly designed to handle oil products, some 50,000 b/d of its template capacity are reserved for crude oil, with the initial 20,000 b/d of its crude export facilities to be in place by start of 2004. Crude and products produced by Lukoil will be delivered to the terminal by rail and river.

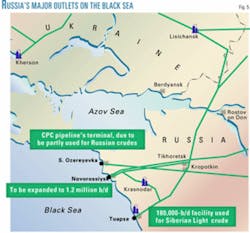

On the Black Sea (Fig. 5), Transneft is pushing ahead with plans to increase trans-shipment capacities of Novorossiysk, Russia's largest oil port capable of handling more than 900,000 b/d. Although no schedule has been disclosed, the projected boost to 1.2 million b/d is likely to materialize by around 2005. Capital requirements of this project, involving expansion of feeding pipelines, are estimated between $400 million and $1.2 billion.

Unlike Novorossiysk, a nearby oil terminal at South Ozereyevka suffers from a lack of Russian crude supplies. The offshore loading facility was built northwest of Novorossiysk in mid-2001 by the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) to facilitate seaborne exports through its pipeline from Kazakhstan's Tengiz oil field.

The 40 in., 940-mile line, which has already consumed more than $2.6 billion of initial investment, was originally projected to ship up to 1.4 million b/d, with about 350,000 b/d reserved for Russian crude that would be available through a planned interconnection with Transneft's pipeline feeding Novorossiysk.

The expected injection of Russian crude was essential for making the $4-billion project feasible even at today's shipping tariff of $26.30/ton (or about $3.50/bbl).

The connection line could be quite short (30-60 miles) and quickly built (within a month) for no more than $50 million. Potential suppliers of Russian crude, however, found the interlink option too expensive to use (with more than $1/bbl of additional tariff), and in September 2002, CPC had to scale down the originally planned capacity to 1.13 million b/d.

Still, the option is open for the future.

Meanwhile, the CPC capacities are to be increased to 1.06 million b/d in 2006 from the current 480,000 b/d. This will require additional investment of $1-1.3 billion, including $250-300 million due to be provided by Russia. And the Russian government, which has a 24% stake in CPC, is insisting on raising the line's tariff to $38/ton (or $5/bbl) to make the pipeline profitable, but hardly competitive.

Meanwhile, boosted by new deliveries from Karachaganak condensate field in northwest Kazakhstan, CPC plans to ship 350,000 b/d this year, rising to 410,000 b/d in 2004.

Until recently, the port of Tuapse, southeast of Novorossiysk, was reserved for exporting Siberian Light crude. Partly for this reason, last year its capacity of 180,000 b/d was used at only 55%. This year, Transneft plans to cease separate exports of this prime blend, which would substantially boost the port's utilization and uncork Russia's oil pipelines for additional exports of at least 120,000 b/d of the traditional Urals blend.

To complete the Black Sea picture, Moscow's recent interest in joining the projected Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) should be brought in.

In late July, the Kremlin administration asked the energy ministry to give its expertise on a plan prepared by Russian construction firm Rosneftegazstroy, which proposed to build a connecting line between the port of Novorossiysk and BTC's section in Georgia.

Despite the strong resentment towards the rival BTC in some Moscow circles, the plan is worth consideration, given the growing concern about the already restricted traffic through Turkey's Bosporus waterway.

Frontier outlets

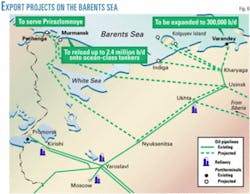

In the Far North (Fig. 6), all the proposed oil-export projects gravitate towards an ice-free passage to the Atlantic, heated up by the Gulf Stream. In particular, Gazprom's project envisions a 300,000-b/d oil terminal at Pechenga, northwest of Murmansk, to serve the Prirazlomnoye oil field in the Barents Sea.

The Northern Gateway scheme, with proposed capacity of up to 500,000 b/d, is designed to facilitate oil exports from the Kharyaga, Northern Territories, and other upstream projects in the Nenets Autonomous District.

Separately, Lukoil's oil terminal at Varandey (the first private oil-export facility in Russia) also aimed at reloading on to larger, ocean-class tankers at Murmansk, is to be expanded to 300,000 b/d from its current 120,000 b/d.

Still, all those northern projects have been recently overshadowed by an ambitious Murmansk project, proposed last November by Lukoil, Yukos, TNK, and Sibneft. The project, which was joined by Surgutneftegaz (SNG) and may be also backed by ConocoPhillips, Marathon Oil Corp., and Total SA, envisions constructing a major pipeline, which would bring West Siberian oil to Murmansk, and using a new oil port's facilities for loading VLCCs.

The pipeline would follow one of two proposed routes, running from Tyumen oil fields to the ice-free port either 1,600 or 2,200 miles. Originally, projected capacity of this oil transportation system was to reach 1.2-1.6 million b/d by 2008, with estimated capital needs varying between $5.1 billion and $5.7 billion and possibly up to 2.4 million b/d later.

In late June, however, the Russian oil majors involved in the project signed a memorandum of understanding with Transneft and the Ministry of Energy, which has boosted the 48-in. line's ultimate capacity to 3 million b/d. With only 200,000 b/d reserved for third parties, the MOU has distributed the line's remaining maximum throughput as follows: 1 million b/d to be filled by Yukos, 660,000 b/d by Lukoil, 500,000 b/d by TKN, 400,000 b/d by Sibneft, and 240,000 b/d by SNG.

Transneft will build and operate the line, provided that its feasibility study yields positive findings. Given that the study, which has been delegated to the energy ministry, is to be completed by the end of 2004, Russia's biggest oil pipeline is expected to be operational in 2007.

Although the grandiose project is persistently advertised (for obvious political reasons) as the best way for exporting Russian crude to the US, it is unclear why it should not facilitate less expensive oil exports to the closer European markets (Table 2).

Far East's oil export projects are less ambitious and call for serving oil developments in Sakhalin and East Siberia. The ExxonMobil Corp.-led Sakhalin-1 scheme envisions expansion of the oil port of De Kastri (on the mainland, across the Tatar Straits) to 240,000 b/d from its current capacity of 40,000 b/d. By 2006-07, the consortium plans to build a 140-mile pipeline connecting De Kastri with its oil fields offshore northeastern Sakhalin.

In turn, the Royal/Dutch Shell-led Sakhalin-2 project provides for an oil terminal at Prigorodnoye (at southern Sakhalin) with capacity of up to 200,000 b/d. Starting from 2006, crude oil and condensate will be delivered to the terminal through a 610 mile, 20-24 in. pipeline from the offshore Piltun-Astokhskoye and Lunskoye fields in the north (Fig. 7)

Until recently, future oil exports from Eastern Siberia have been moot in two different (and actually conflicting) ways (Fig. 8). Both the options were based on a pipeline starting from Angarsk (near the city of Irkutsk) but ending either in northeast China (Yukos' proposal) or near the Russian Pacific port of Nakhodka (Transneft's suggestion).

The former's project riskily locked Russia's eastern oil in the Chinese market but could be well supplied by the region's projected oil production (at some 600,000 b/d by 2010). The latter one, actively lobbied by the Japanese (offering Moscow some $5 billion in low-interest loans), enjoyed a geopolitical advantage of export diversification but had a serious weak point: the lack of the region's available supplies to support a larger oil pipeline with a minimum required capacity of 1 million b/d.

And not the least consideration: Yukos' 1,420 mile, 40-in. pipeline would cost the Russian major $2.2 billion (and $700 million to China's CNPC), while required investments in Transneft's 2,410 mile, 48-in. alternative (wholly paid by the Russians) are officially estimated at $5.8 billion.

It is noteworthy that, when (and if ever) built, the Angarsk-Nakhodka pipeline would be one of the longest in the world—nearly three times the length of Trans-Alaskan Pipeline—and would traverse terrain nearly as harsh. It makes many analysts mistrust official estimates and argue that $8 billion is a more realistic capital need for the state-run monopoly's project.

In May 2003, the Russian cabinet made a compromise (though "not yet final") decision to give the green light to Yukos' plan to build the Angarsk-Daqing pipeline that would be supplemented by the Angarsk-Nakhodka line when (and if) East Siberian (and Yakutian) oil supplies are sufficient to fill it.

Although it was presented as a Solomonic tradeoff, it seemed to have actually buried Transneft's project for any foreseeable future. Furthermore, the surviving scheme was cemented in late May by a 26-year supply deal between Yukos and China National Petroleum Corp., which provided for total pipeline deliveries of up to 700 million tons (more than 5.2 billion bbl) of Russian crude, starting from 20 million tons/year (400,000 b/d) in 2005-09 and increasing to 30 million tons/year (600,000 b/d) in 2010-30.

Still, the Russian government's reaction to the deal was very cool as Moscow started its preelection campaign against Yukos' politically ambitious master Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

The final decision on the pipeline's route, which was expected to be sealed during a visit by Russian premier Mikhail Kasyanov to Beijing in late September, has been indefinitely postponed. Whatever the decision, though, it is unlikely that Russian oil will start to be pumped to China (as earlier envisioned) in 2005; under the original plan, construction was to have begun before yearend 2003.

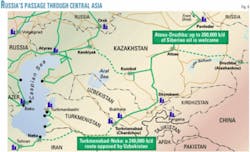

Passage through the south

Last but not least, Russia's oil exports can be also debottlenecked in the south by increasing supplies through the Caspian and Central Asian deserts to Iran.

Among several related projects, a pipeline connection between Turkmenabad (former Chardzhou) in Turkmenistan and Neka in northern Iran looks the most workable and cheapest option (Fig. 9). The project, favored by Transneft, would allow shipment southward to Iran of up 240,000 b/d of West Siberian crude, starting from 100,000 b/d in the near future.

Currently, the Russian pipeline monopoly uses only the northern portion of the Omsk-Pavlodar-Shymkent- Chardzhou pipeline built in 1983 to feed the three Central Asian refineries that were short-sightedly beaded onto it in the Soviet era. Last year, Kazakhstan's 160,000-b/d Pavlodar refinery received through the line a mere 55,000 b/d supplied by TNK, Lukoil, and other producers of West Siberian crude.

Yukos also uses the Omsk-Pavlodar section for further oil shipments to China by rail. Last May, Russia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan set up a working group to study reactivating the southern, Pavlodar-Chardzhou section. But Uzbekistan, which is currently supplying the Seidi refinery at Turkmenabad (Chardzhou) from the Kokdumalak field on the Turkmen-Uzbek border, strongly opposes (and actually blocks) reopening the line from Pavlodar for fear of losing its oil supply monopoly to Seidi.

Separately (and alternatively), Kazakh pipeline operator KazTransOil (KTO) talks with Transneft on shipping West Siberian crude through a recently proposed pipeline to China. The 640-mile line, with projected capacity between 600,000 b/d and 1 million b/d, would go eastward from Atasu (located halfway between Pavlodar and Shymkent on the Omsk-Chardzhou pipeline) to Druzhba (Alashan'kou) on the Kazakh border with China's Xinjiang province, targeting the Karamay refinery at the western end of the Chinese pipeline system.

The proposed connection is a part of the ongoing project aimed at bringing crude oil from western and central Kazakhstan (including the northern Caspian) to the country's underutilized eastern refineries (at Pavlodar and Shymkent) and further on to western China.

The already-started construction of the 1,740 mile Atyrau-Kenkiyak-Kumkol-Atasu-Druzhba pipeline is estimated to cost $2.7 billion, while its Atasu-Druzhba section, which can be built within 2 years, is expected to require around $850 million.

Export-driven output

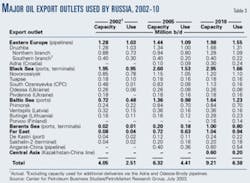

While some of these projects are still in blueprint, others (such as the Adria reversal and the Primorsk expansion) are set to bear fruit within a year. All in all, the ongoing and envisioned projects must boost the existing export capacity of major outlets, wholly or partly available for Russian crude, to more than 6.3 million b/d by 2005 and 9.2 million b/d by 2010 from some 4 million b/d last year (Table 3).

Understandably, not all the incremental capacity will be used by Russia, which will refrain from using foreign facilities and share its own ones with Kazakhstan and other Central Asia's exporters.

Still, Russia will be able to increase its current crude oil exports via major outlets to 4.4 million b/d by 2005 and nearly 6.4 million b/d by 2010 from 2.5 million b/d.

By adding minor export facilities (rail, river, and small sea terminals) estimated to provide 0.6-0.8 million b/d, one will get a fairly reliable rule-of-thumb forecast of Russia's total crude oil exports outside the FSU: 5-5.2 million b/d by 2005 and 7-7.2 million b/d by 2010.

Further on, adding inland demand for crude oil (i.e., refinery intake, direct use, and losses) at projected fairly stable 4 million b/d plus net exports inside the FSU (including transit via Ukraine) at probable 0.8-0.9 million b/d leads to the conclusion that Russia's crude oil output (including field condensate) is likely to reach 9.8-10 million b/d in 2005 and 11.8-12.1 million b/d in 2010.

This seemingly incredible finding has been implicitly supported by recent output projections by Russian oil majors (including Yukos, Lukoil, and TKN).

In particular, speaking at the 2nd International Pipeline Forum in Moscow in late May, TKN's then-Pres. Simon Kukes made public a comprehensive overview of Russian companies' production plans targeting a total of more than 10 million b/d in 2007 and nearly 11.6 million b/d in 2012, even without accounting for Russia's offshore production estimated to contribute in mid-term 0.6-0.8 million b/d (Table 4).

Admittedly, these projections look trustworthy only if world oil prices are fairly stable in real terms, with the OPEC basket price staying above $20/bbl.

If the reference oil price nosedives to $15-18/bbl, the poorer upstream and midstream economics will probably lower both Russia's oil output and its non-FSU exports by around 0.5 million b/d in 2005 and by some 1 million b/d in 2010.

Still, Kukes assured that all the reviewed plans were based on $16-18/bbl for Brent price and at least 15% internal rate of return for related oil projects.

Anyway, until the country's oil resources are actually depleted, Russia's oil production growth will surely be determined by available export capabilities.

Russian oil companies will export (and, hence, produce) as much crude as they can profitably sell. In turn, Moscow political elite—lobbied, corrupted, or objectively interested in promoting the national oil business—will do whatever is needed to keep the big oil show going.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude for useful insights, critical comments, and invaluable information provided by Yakov Ruderman, PetroMarket Research Group; Aleksey Aleksandrov, the RF Energy Ministry; Mikhail Tigashov, TransNafta; Sabr Yessimbekov, KazTransOil; and Tamara Varava, UkrTransNafta.

The authors

Eugene Khartukov is general director of the Center for Petroleum Business Studies, Moscow; vice-president (for Eurasia) of Petro-Logistics, Geneva; head of World Energy Analysis & Forecasting Group; director for international affairs of PetroMarket Research Group, Moscow; and professor of management and marketing at Moscow State University of International Relations (MGIMO). He graduated with honors diploma (1977) in international economics from MGIMO in 1977; obtained a PhD (1980) in international and petroleum economics and post-doctorate (professorship; 1990) in international and energy economics, both from MGIMO, and since 1994 holds the lifetime title of professor. He is a member of Council of Energy Advisors (US) and the Russian Association for Energy Economics.

Ellen Starostina is head of PetroFinance Consultancy (PFG) and director for finances for the Center for Petroleum Business Studies. She graduated from Moscow-based Plekhanov Academy of National Economy (Faculty of National Economy Planning) in 1981 and obtained a PhD (2002) in petroleum finances and taxation from the same institution. During 1978-2000, she worked as economist and director for finances and economics in various oil and trading companies (including Soyuzregion, Urals, Ukhtaneft, and Impex Oil). Since 2000, she consults to oil companies, legal firms, and commercial banks on oil finances, taxation, and trading. In 2003, she joined the Council of Energy Advisors (US).