COMMENT: More evidence mounts for banning, not expanding, use of ethanol in US gasoline

Year-to-date ozone data from California are confirming the analysis put forth in this space last year.1

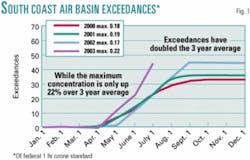

California's switch to ethanol from methyl tertiary butyl ether is a test of the relative merits of oxygenates used in reformulated gasoline (RFG). Through July 31, the ozone exceedances in California's South Coast Air Basini2 are twice the level of the prior 3 years' levels, as shown in Fig. 1. The maximum ozone concentration is up 22%. Exceedances of the 8 hr standard are also up, with the maximum concentration up 40%.

If this were a drug test, it would be terminated after two patient fatalities.

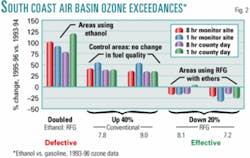

The first fatality occurred in 1995 when America's major cities began using simple-model RFG. To make simple-model RFG, refiners simply reduced the vapor pressure and benzene content of conventional gasoline and added an oxygenate. The vapor pressure and benzene reductions were relatively minor. The biggest change was the addition of either 11 vol % MTBE or 10 vol % ethanol. This provided a rare opportunity to compare the effectiveness of the oxygenates.

Fig. 2 shows that ethanol is defective while MTBE is effective. Ozone exceedances doubled in areas using ethanol-based RFG and decreased 20% in areas using MTBE-based RFG.

Correcting for defects

Ethanol's defects easily explain the observed ozone increases. These defects include its tendencies:

To produce more nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions.

To permeate through the seals in automotive fuel systems.

To degrade driveability and increase exhaust emissions.

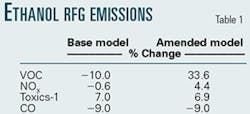

When the US Environmental Protection Agency's Complex Model is corrected to reflect these defects, it shows that ethanol-based, simple-model RFG increased the emissions of ozone precursors (NOx and volatile organic compounds) and carcinogens. Table 1 compares the emissions projected by EPA's base model and the more-complete model that reflects ethanol's defects.

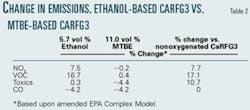

The emissions relative to nonoxygenated California Phase 3 RFG (CaRFG3) when compared with ethanol-based CaRFG3 and MTBE-based Ca RFG3 are shown in Table 2. The model shows that both ozone precursors and carcinogenic emissions increase with the ethanol-based fuel. The doubling of ozone exceedances in Fig. 1 confirm that ethanol's defects are real.

The experiment will not be complete until the end of the 2004 ozone season, when all CaRFG3 is ethanol-based. But with only 70% of the southern California RFG3 being made with ethanol and resulting in the observed adverse ozone impact, the experiment should be stopped.

RFS delay needed

If Congress is not ready to end the ethanol experiment, it should definitely wait until the end of 2004 to enact a Renewable Fuel (ethanol) Standard (RFS). By then it will have data from California, Connecticut, and New York.

The ozone increase in California is predictable because the refiners cannot change other parameters to offset the ethanol defects. Ethanol's adverse ozone impact may be obscured in Connecticut and New York as refiners lower the sulfur content of their gasoline.

If Congress refuses to wait for the data, it must insert an environmental escape clause in the RFS legislation. The clause must allow the governor of any state that experiences increases in ozone exceedances following an increased use of ethanol in all or part of the gasoline in his state to opt out of the RFS program and ban the use of ethanol in his state's gasoline. To prevent harming other states, the volume requirements of the RFS should also be decreased, based on the state's market share of ethanol demand.

Political science

The political science backing ethanol is understandable; support of ethanol-from-corn has become a litmus test for presidential candidates. But they cannot continue to buy votes by sacrificing air quality and people's health.

The political science is fueled by the ethanol producers' oligopoly that has created the illusion that ethanol-from-corn benefits the nation's family farmers and energy balance.

We all know that stories need a sponsor to stay alive. If we ask who wins and who loses if MTBE is banned and ethanol is mandated, we quickly conclude that the ethanol industry is the only clear winner.

The volume loss associated with switching from MTBE to ethanol will improve refiner's margins. But the punitive-liability lawsuits that grow out of that transition can erase those profits. Also, ethanol's negative impact on air quality will force more fuel changes and fixed-source controls in the long term. Therefore, while the campaign to discredit MTBE has caused refiners to want to get rid of MTBE, they are unlikely to be the source of the anti-MTBE public relations campaign. Obviously, MTBE producers did not undertake this campaign.

A recent survey of Californians shows the people did not do it. A solid majority of Californians (58%) believe that air pollution is a serious health threat to themselves and their immediate families. Accordingly, state residents rate air pollution (30%) as the most important environmental issue, followed distantly by water pollution (10%).3 Also, people just do not like higher gasoline prices.

The energy balance of ethanol, discussed in the article on p. 20, is breakeven at best, with the current economically obsolete dry-mill ethanol technology that requires a subsidy to be economic.

(Note that a 2002 US Department of Agriculture study reported a positive energy contribution.4 But that study also assigned a large piece of energy to the animal feed by-product. If that energy is allocated to ethanol, as it should be, USDA's numbers also show a breakeven energy balance.)

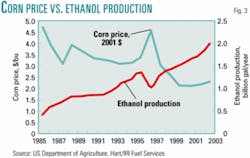

Plotting corn price vs. ethanol production casts doubt on the benefit of the ethanol-from-corn program to farmers (Fig. 3). The data show corn prices decrease as ethanol production increases.

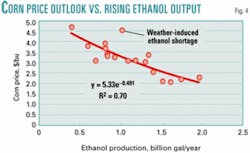

A simple correlation shows that by the time the RFS hits its 5 billion gal/year target, the corn price should be 50¢/bushel (Fig. 4).

Unanswered questions

As a nation, we must ask our leaders and ourselves:

- If corn prices did not increase with ethanol production, where did billions of dollars go?

- How do the observed lower corn prices help our farmers?

- How does transforming fossil fuel to "renewable" fuel help our energy balance?

- How can we justify degrading air quality in our major cities to "subsidize" a farmer by giving him a lower price for his corn?

- How can we justify the government sponsoring any program that harms public health? With the tobacco subsidy, we each get to choose if we smoke, chew, or dip. But we all must breathe.

Why not end an experiment that has failed to improve corn prices, has failed to improve our energy balance, and has degraded air quality?

References

1. Hodge, Cal. "Ethanol use in US gasoline should be banned, not expanded," OGJ, Sept. 9, 2002, p. 20.

2. http://www.arb.gov/adam/cgi-bib/db2www/ozonereport_annual.d2w/start and hot links at that site.

3. Public Policy Institute of California, Statewide July 2003 PPIC Survey, Special Survey on Californians and the Environment in collaboration with the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, the James Irvine Foundation, the David & Lucile Packard Foundation, Mark Baldassare, Research Director and Survey Director.

4. Duffield, James and Wang, Michael Wang. "The Energy Balance of Corn Ethanol: An Update," Hosein Shapouri, US Department of Agriculture, Office of Chief Economist, Office of Energy Policy and New Uses, Agricultural Report No. 813.

The author

Cal Hodge is president of A 2nd Opinion Inc. (A2O). His firm advises on regulatory, clean fuels, and economic issues. He has 35 years of experience in refining and petrochemicals economics, strategic planning, fuel formulations, governmental affairs, litigation, product distribution, industry analysis, and regulatory compliance. Prior to founding A2O in 1998, Hodge held positions with Amoco Corp., Pace Consultants & Engineers, and Valero Energy Corp. His early focus included a specialization in unleaded premium gasoline blending prior to the introduction of unleaded regular. Hodge developed an expertise on refinery economics in the late 1960s and has taught other engineers and clients basic refining economics principles and applications. He gained further expertise in gasoline regulations, clean fuels, and air quality by participating in the regulatory negotiation that resulted in US federal reformulated gasoline regulations. Hodge graduated from the University of Kansas in 1968 with a BS in chemical engineering. His e-mail is [email protected].