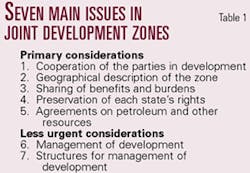

Seven fundamental issues frame JDA negotiations

JOINT DEVELOPMENT AGREEMENTS-2

At least five and as many as seven fundamentals should be in the forefront when negotiating an initial joint development agreement.

The first of the main issues is the cooperation of the parties in development. The agreement should include specific provisions that set out the actual goals of cooperation as well as the implications of such cooperation in terms of the behavior of the governments. In particular, it will need to make clear that the development of the zone may take place only in accordance with the terms of the joint development agreement, and therefore neither state will be entitled to act unilaterally in respect of such development.

Area of the zone

The second—and perhaps the most obvious—aspect of the joint development agreement is the geographical definition of the zone to which it will apply.

The actual area of the zone will normally be described in terms of geographical coordinates joined by appropriate lines. Of course, there will also be a depth element to the zone—the sea, seabed, and subsoil—and it will be necessary to take this into account.

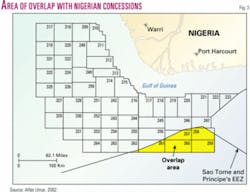

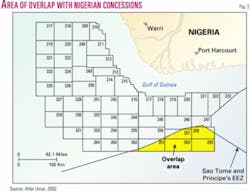

But how is agreement on the actual area of the zone arrived at? In the context of a boundary dispute, the area of the zone will often be determined—if not specifically defined by—what might be called the area of "overlapping claims" of the two parties (Fig. 3).

However, this should not give the impression that what will normally happen is that each party will have a well publicized claim, say, in relation to the extent of their rights in the continental shelf and-or exclusive economic zone, and that the agreed joint development zone will inevitably be identical with the area of overlap of such claims.

First of all, it is quite possible that one or both of the parties will not have made a specific public claim concerning the extent of their territory or rights. Secondly, even if they have, it is possible that during negotiations they will reach some level of compromise in relation to such claims, such that a party might abandon areas where its claim is not particularly strong.

In a sense, this is what happened in the case of the Nigeria-STP JDZ. In March 1998, São Tomé e Príncipe passed a law that established the limit of its maritime claim at the median line with its neighbors. Nigeria's public claims in relation to maritime areas were no more specific than a claim to a 200-mile exclusive economic zone, subject to agreement with neighboring states.

The finally agreed area of the joint development zone did have, as its northwestern boundary, the STP declared median line. But whereas Nigeria's 200-mile EEZ claim does appear to have been the basis of the southwestern boundary of the zone, it is clear that this 200-mile claim was not taken as the limit of the zone all the way up to the territorial waters of STP. Instead, a line giving limited effect to the presence of STP forms the southeastern boundary of the zone.

Nevertheless, it is still true to say that the area of the zone will normally consist of at least part of the area claimed by both parties, in diplomatic negotiations if not actually publicly. This leads to the question of what happens in a situation where it is not only two parties claiming the relevant area, but three or even more?

In some ways the best solution might be to attempt to involve such other countries in the joint development zone and structure a joint development agreement on a multilateral basis.

Although certainly more complicated, there is no conceptual reason why this cannot be done, and although this article assumes throughout that there are only two parties to the agreement, this does not need to be the case.

If, however, it proves impossible to involve other countries with their own claims in the joint development scheme, this may indeed cause real problems for the setting up of the zone, since, depending on the strength of these claims, the uncertainty which the establishment of the zone sought to remove will still be present in some degree. However, if the two parties decide to proceed, despite this element of uncertainty, it might be useful for them to stipulate in their agreement that any dealings or negotiations with such third parties in relation to their claims will be coordinated by the parties to the agreement, to ensure a consistent approach.

Sharing benefits, burdens

The third issue that will almost certainly have to be dealt with at the outset is the sharing of benefits and burdens.

The burdens may well be a secondary issue in the mind of a government that is in the process of agreeing to put aside a dispute and set up a joint development zone. The main concern of the negotiators will almost certainly be, "What's in this for us?" Yet, as a matter of practicality, the agreement that is eventually negotiated will probably require both parties to contribute to the costs of the zone—both in terms of finance and responsibility.

But it is the benefits of the zone that the parties will most likely have on their minds, and the question arises as to the proportions in which such benefits should be shared. In principle, on the basis of attributing equality to each party's claim, there is a good prima facie argument for the benefits being shared equally. However, other factors might need be considered.

The allocation of shares might end up reflecting the fact that whereas governments are usually extremely reluctant to abandon claims to territory or maritime areas, there may be less of a political problem in relation to the sharing of the benefits that accrue.

It is therefore possible that in the course of negotiations, concessions concerning respective shares will be made by the parties, perhaps in recognition of the weakness of their claim, or possibly as a result of other political considerations. Whatever the reasons, this has actually happened on occasion: in the case of Nigeria-STP, Nigeria takes a 60% share against STP's 40%.

An issue often raised, although not necessarily in the context of structuring a joint development agreement, is the basis on which states are able to reallocate their rights, for example their right under the Law of the Sea to exploit the resources of the continental shelf. Even if a joint development zone is being set up, are the states actually able to "pool their rights" for the purposes of cooperation?

This question naturally has a bearing in relation to the chain of title to petroleum, a matter which will be of some concern to oil companies. However, in practice the problem is largely academic.

Provided the governments have agreed to pool their rights and allow resources to be dealt with in the way agreed under the treaty, it is difficult to envisage how title to such resources could seriously be questioned somewhere down the line on the basis of this issue.

The one rider to that conclusion is that it might be necessary to ensure that appropriate legislation concerning property rights has been enacted in both countries, if required, to prevent any dispute arising.

Preservation of rights

The fourth, essential ingredient of the joint development agreement is a provision that preserves the two states' claims in relation to territory or maritime areas.

The parties will almost certainly want to make it clear that their agreement to set up a joint development zone is not intended to nullify their long-term claims to the area of the zone, and that whatever provisions have been agreed in respect of the zone may not be taken as an indication of either party's position in relation to the extent of its residual rights in the zone.

A "without prejudice" clause should in principle serve this purpose and in most cases will provide sufficient comfort to both governments. Having said that, in the case of the initial Timor Gap agreement between Australia and Indonesia, under which the resources in the subzones nearest each country were initially split 90/10 in favor of that country, it would have been hard to imagine the party that had settled for only 10% of the benefit from such a subzone seriously being able to maintain a long-term claim to the subzone. But that was an extreme case.

Resources to be developed

The fifth main issue is agreement on the resources that will be the subject of the joint development agreement.

In many cases, the JDZ will have been set up specifically for the purpose of exploiting petroleum resources, which purpose would have been the catalyst for putting the dispute aside temporarily. However, the parties may wish to agree on joint development in relation to other resources, both living and nonliving. The precise resources to be covered will need to be specified in the agreement.

Types of structures

The next two issues are matters which, although very important, could just about be left out of an initial agreement and agreed upon at a later date.

The first is the management of development. This concerns the question of who precisely will be authorized to undertake development activity, and who will authorize such activity.

In the discussion of this subject, this article will concentrate on the exploration and exploitation of petroleum. In practice, the main issue that the parties will wish to consider is the manner in which exploration and exploitation will take place and—where necessary—how it will be decided which concessionaire will be granted the right to conduct such activities and on what terms.

Having earlier noted the limited benefits of adhering too closely to the structure of precedents, it must be noted that, among the precedents, the structures for management of development tend to fall into three separate broad categories. While it would probably be best for the parties to consider their approach to this issue on the basis of their own circumstances, it seems likely that whichever solution they arrive at will more or less fit into one of these categories of structure.

Single state structure

The first of the categories of structure involves what might be called single state management.

This is a situation where the states agree that one of them will be responsible for managing the development of the zone on behalf of both states. It will probably involve that single state managing the zone as if it were an undisputed part of its territory or maritime areas, and as a result applying its own legislation and regulations, in particular in relation to the collection of revenue.

Any revenue collected would then—presumably after deduction of appropriate expenses—be shared with the nonmanaging state in the agreed proportions. And that is really it. It sounds simple, and conceptually it is. Provided that the nonmanaging state is happy to trust the managing state to pass on its agreed share of the benefit, such a system is highly commendable because of its simplicity.

Two-state structure

The second structure found in the precedents is what might be called the two-state/joint venture model.

The attractive aspect of this model for governments is that each government will be entitled to nominate its own concessionaires to undertake development activity. Having each nominated one or more concessionaires to develop a specified part of the zone, the governments will then be required to ensure that their concessionaires enter into a joint operating agreement with each other.

The concessionaires will have to divide the petroleum recovered by the joint venture in the shares that have been agreed by the states. Each concessionaire's share will then be subject—for fiscal and revenue purposes—to the terms of its concession agreement, in accordance with the normal fiscal arrangements of the state that awards the concession.

So far, the arrangement sounds quite simple. However the question arises as to which laws and regulations—both in relation to petroleum activities and otherwise—will apply in relation to the zone. In the case of the 1974 Japan-South Korea JDZ Agreement, this problem was solved by stipulating that whichever of the concessionaires was chosen to act as operator in a particular block, the identity of the government that awarded the operator's concession would determine which country's laws applied in the block. This naturally made the choice of operator a matter of even greater concern for governments than it normally would be.

Other alternatives would be either to choose one nation's law for the whole zone—a politically difficult choice—or to create a new body of law and regulations that applies to the zone. To do this would be rather complicated and would negate much of the simplicity otherwise present in this structure.

Joint authority structure

The third and final structure apparent in the precedents is the joint authority structure, which might also be called an interstate joint venture structure.

In this scenario, neither state is directly responsible for the management of development and neither is able to directly choose its own concessionaires. Instead, both states delegate the power they have in respect of such management—or even their actual right to the resources—to a single body, which could be called a joint authority. It happens that the Nigeria-STP arrangements fall into this category of structure.

If a joint authority is to be set up, it will be necessary to agree on the way the authority should function, and to ensure that it has the appropriate power for these purposes. The parties might wish to agree to attribute legal personality to the joint authority under the laws of each nation, if only so that it will be able to take legal action—and where necessary, have action taken against it.

The joint authority will, in some way or another, act as a representative of both state parties. But there is some room for flexibility in relation to the functions of the authority. At one extreme, it is possible for both states to delegate all or nearly all their powers in relation to development to the joint authority and leave it to run the zone as if it were a separate government.

Although in many ways this is a very simple solution in terms of management, there might be real reluctance, from a political point of view, for states to delegate so much power. At the other extreme it is possible to leave the role of the joint authority as purely administrative, with the authority carrying out duties on the basis of policies that have been agreed and set by the two participating governments. Positions in between these two extreme positions are also possible.

Nigeria-STP Joint Authority

As far as the Nigeria/STP Treaty was concerned, the system set up for the joint authority was somewhat closer to the second extreme.

Under the treaty, a council of ministers was also set up. The idea behind the council of ministers is that ministers of both governments should have overall responsibility for all matters relating to the exploitation of resources in the zone. Such "overall responsibility" involves the ultimate power to approve the authority's rules and regulations, its accounts, and the award of and terms of any concessions.

The council also has the power to give directions to the authority on how to discharge its functions. The treaty stipulates that the council is to adopt its decisions by consensus.

While this structure undoubtedly leaves the two governments in a supreme position vis-à-vis the authority and allows them the final word on all matters of importance, for most purposes that is all it is—the final word. It is the authority itself that, as well as performing all necessary administrative tasks, makes all those decisions that require final approval by the council of ministers.

Indeed, the treaty sets out in great detail the functions of the authority, which include the negotiation, issue, and supervision of concessions, the preparation of budgets and accounts, the supervision of various issues, including those relating to safety and the environment, and—perhaps most importantly—collecting and distributing the proceeds from concessions awarded.

Choosing the appropriate structure

So how do the parties choose which of these structures is the most appropriate?

In truth, it will be a question of considering all the circumstances in each case: political, economic, and practical. In terms of simplicity and practicality, it has already been noted how simple the single state model is. As against this, the establishment of a joint authority—involving the creation and maintenance of an additional bureaucracy at the very least—will inevitably be more complicated.

Some single state structures seem to have been adopted in the past, owing to the fact that one state had a more advanced petroleum infrastructure than the other and the fact that the nonmanaging state, for whatever reason, felt it was able to trust the other state to manage the zone and pass on its share of the benefits.

In the case of Nigeria-São Tomé e Príncipe, both states could have benefited from reverting to the simplicity of single state management, in this case by Nigeria, which had a relatively advanced petroleum infrastructure. Instead, however, the joint authority structure was adopted. This indicated that in the case of STP at least, there was one other factor that overrode the rest, and that was STP's desire for a measure of equality.

This desire may have had two underlying bases.

Firstly, STP may have been interested in developing its own independent petroleum infrastructure, and if it left Nigeria to manage the zone by itself, STP would have lost the opportunity to build up valuable experience. But as well as that, and this applies to all states and not just STP, it is difficult to overestimate the desire of states to be treated equally.

In situations where states truly desire political equality, one of the two joint structures is more likely to result. Moreover, there might even be a factor beyond the pure desire for political equality. It is quite possible that a government might feel that it is somehow compromising its claim to the area of the zone if it allows the other state to be fully responsible for its development. It may thus insist upon a joint structure, despite the headaches that might be involved in setting it up.

Duration

The seventh and last main issue, which almost certainly will be dealt with in the initial agreement, is the duration of the joint development arrangement.

Although the duration can be agreed later, it is hard to imagine such a simple yet important aspect not being agreed at the outset. However, it is technically possible, and indeed might even be appropriate if the parties' intentions—whether spoken or unspoken—are that the joint development arrangements should continue indefinitely, it being difficult to see at the time of the agreement why the underlying dispute should ever disappear.

Either way, duration will have to be agreed at some point, and the issue will be considered further below.

The next, concluding part of the article will treat other topics that are either not always applicable or that may be left for a later date before receiving proper consideration, including some that are extremely important and must be dealt with carefully.

Next: Other important issues loom in JDA negotiations.