North Sea oil reserves: half full or half empty?

The impending decline of North Sea crude oil production shows that yet another major oil province is entering its final production phase.

In addition to providing further evidence of accelerating global oil depletion, this trend points to Europe's increasing dependence on imported oil

While the steepness of the North Sea production decline slope can be ameliorated somewhat, the inevitable consequence will have important implications for supply-demand patterns worldwide.

History

Initial interest in the North Sea's hydrocarbon potential was triggered in 1959 by the discovery of giant Gronigen gas field in the Netherlands.

This find "caused geologists to revise their thinking on the petroleum potential of the North Sea."1

Consequently, during the 1960s, the North Sea witnessed febrile oil exploration activities.

In 1969-70, two major oil finds were made: Forties field on the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) and Ekofisk on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS).2

Then, during the 1970s, a myriad of further discoveries were made in this highly prolific region.

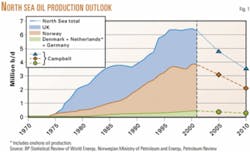

These finds led to an ever-increasing oil output that eventually resulted in North Sea production exceeding 6 million b/d by 1996. It was only after a quarter of a century of uninterrupted record-breaking that output began to stall and then plateau at 6.2-6.4 million b/d (Fig. 1): a clear sign that production limits were being reached. Total oil output even began to drop slightly after a record 6.43 million b/d in 2000,3 leading some experts to conclude that North Sea output had peaked.4

Although the North Sea is sometimes taken as a single petroleum region, it is in fact made up of five distinct sectors: the UKCS, the NCS, and the continental shelves of Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany—with each sector having its own background, petroleum reserves, and exploitation profile. It goes without saying that the UKCS and NCS dominate the group, as they jointly account for over 90% of North Sea petroleum reserves.

UKCS

The UKCS had initially attracted most of the attention in the North Sea. Major oil companies, led by BP PLC and Royal Dutch/Shell Group, were soon pouring billions of dollars into exploration before putting more money into the exploitation of discovered oil and gas fields.

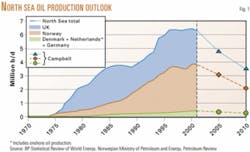

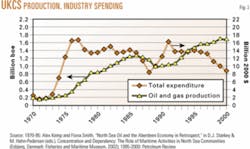

The high oil prices of the late 1970s and early 1980s underpinned this initial effort. In fact, capital investment in the UKCS came to parallel—with a 1-year lag—the ups and downs of oil prices (Fig. 2). For example, investment duly nosedived in 1987-88 after the oil price crash of 1986. Moreover, the two major investment waves (with respective maxima in 1977 and 1991) gave rise to two major production drives (with maxima in 1986 and 2000). Thus, between the investment and production peaks, there was a 9-year lag.

Altogether during 1970-2000, some $358 billion has been spent on the UKCS ($230 billion in capital expenditures, or capex, and $128 billion in operating expenditures, or opex) for a total oil and gas output of around 29.6 billion boe (19.5 billion boe for oil and 10.1 billion boe for gas). That works out to an average cost of $12/boe.

The lack of investment recovery on the UKCS during 1999-2001—notwithstanding the trebling of oil prices during 1999—was a sure sign that investors' interest has dwindled to an all-time low. And even EnCana Corp.'s discovery of Buzzard oil field in 20015 and its 400 MMboe of reserves—thus the largest UKCS find since Schiehallion field in October 19936—failed to revive interest in the northern UK waters. Rather, it seems that investors took Buzzard for the exception confirming the rule.

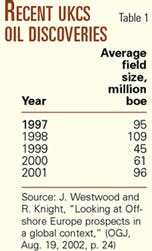

Notwithstanding Buzzard, the average size of oil fields discovered on the UKCS during 2001 amounted to only 96 million boe, roughly twice the 1999 average but in line with previous averages (Table 1).

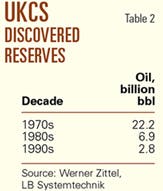

Moreover, decreasing reserves is yet another sign of a declining discovery rate. As shown in Table 2, after the record 22.2 billion bbl of oil discovered during the 1970s, every subsequent decade yielded only a third as much as the previous one. Taking this ratio as a rule of thumb, the next decade should yield 1 billion bbl of reserves.

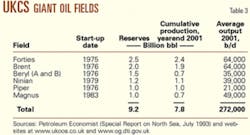

Also worth a mention is that the UKCS giant fields (i.e., oil fields with over 1 billion bbl of reserves) are dying off (Table 3). The six UKCS giants with combined reserves of 9.2 billion bbl have only 1.4 billion bbl left to be produced, and their total output has dropped to only 272,000 b/d (only 13% of total UKCS production).

The 10% tax hike on the Corporation Tax (CT) for UK companies operating in the North Sea, announced in April 2002 by the British government, only added insult to injury.7 John Browne, BP's chief executive, commented, "This tax change was wrong...the former tax system wasn't perfect, but it was effective."8 In order to counterbalance the ill effects of the CT increase, the North Sea royalty tax of 12.5% was abolished effective Jan. 1, 2003.9 But the harm had been done.

Notwithstanding the commanding efforts of the Department of Trade and Industry and its Satellite Accelerator initiative, it is difficult to see how the 315 undeveloped discoveries on the UKCS could be brought on stream "before the window of opportunity closes as decommissioning of existing infrastructure gathers pace."10

Nevertheless, over the next 2 years, some 150,000 b/d of new production is scheduled to come on stream: 50,000 b/d in 2003 and 100,000 b/d in 2004.11

Summing up, energy consultants Wood Mackenzie forecasted that "UKCS oil production could fall by 90% by 2020."12 And reserves expert Colin J. Campbell predicted that by 2005 UKCS production will have plummeted to only 1.77 million b/d13—barely enough to supply UK domestic consumption.

The UK government still was placing its hopes on the February 2003 licensing rounds: the 21st offshore and 11th onshore.14 But even if these were to prove partially successful, it still is doubftul they could rekindle the UKCS flame.

NCS

At the onset, NCS was to play second fiddle to the prolific UKCS. Exploration work in the Norwegian sector developed at a much slower pace than in the British one. The investment flow into the NCS sector was not only slower than it was for the UKCS but also much more gradual (Fig. 3).

The gradual inflow of capital into the NCS sector yielded a stepwise increase in oil and gas production. So that, overall, the Norwegians seem to have achieved a smoother development of their petroleum assets than have the British.

Not only did the Norwegian government pull its full weight into the process, but so did domestic oil companies Statoil ASA, Norsk Hydro ASA, and Saga Petroleum AS (now defunct).15

Altogether, during 1970-2000, some $198 billion was invested in the NCS sector ($141 billion in capex, $57 billion in opex) for a total oil and gas output of around 19.6 billion boe—with 14.9 billion boe for oil and 4.7 billion boe for gas.16 Thus, in the NCS, the average cost was $10/boe, some 20% less than in the UKCS.

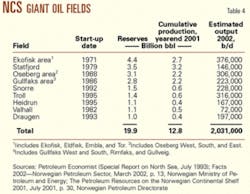

As for giant oil fields, the NCS yielded a total of nine with total reserves estimated at around 20 billion bbl, of which some 7 billion bbl remains to be produced (Table 4). In this respect, NCS is at a clear advantage over UKCS because its giant fields are much younger.

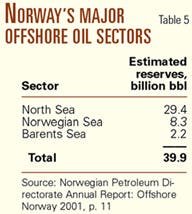

In addition to its NCS (the offshore encompassing the seabed between 56º and 62º N, Norway has another two offshore sectors: the Norwegian Sea (between 62º and 67º N) and Barents Sea (above 67º N)17 But these latter sectors are far less prolific than the NCS (Table 5).

Other North Sea sectors

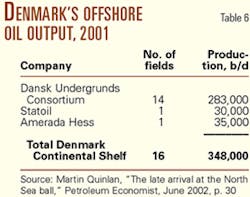

Among the other three smaller North Sea sectors, Denmark is by far the most prolific. For the Danish Continental Shelf, life began in 1962 as the Danish government "awarded an exclusive, 50-year concession over its offshore to AP Moller, the shipping company that then, as now, dominated the country's business life."18

AP Moller established its Maersk AS petroleum subsidiary and created the Dansk Undergrunds Consortium (DUC) with partners Shell (46%) and ChevronTexaco Corp. (15%), while Maersk kept a 39% share.

DUC naturally came to dominate Danish offshore oil production. By 2001, it operated 14 of Denmark's 16 oil fields and produced no less than 82% of Danish offshore output (Table 6).

The unexpected Halfdan oil field discovery in February 1999 brought about a revival of interest in the DCS. It was a very fortunate find, as "there is no normal trap structure over this reservoir."19

Nonetheless, it was estimated to contain some 260 million bbl of recoverable oil and is already flowing at 70,000 b/d with a schedule to plateau at 100,000 b/d in 2005.

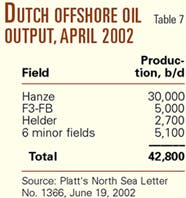

Among the Netherlands nine offshore oil fields, Hanze takes the lion's share. It produced an average of 30,000 b/d in early 2002 out of a total crude production of some 42,800 b/d20 (Table 7). Hanze was the first chalk oil reservoir ever developed in the Dutch North Sea. It began commercial production in August 2001 and is estimated to hold 34 million bbl of recoverable oil.

Germany has had limited success in its North Sea offshore sector. Its main asset is the Mittelplate oil field, which was discovered in 1980 and began production in 1987. The field has estimated oil reserves of 250 million bbl21 and presently provides the major share of Germany's offshore oil production of 18,000 b/d.

Recent exploration

In parallel with declining discoveries, North Sea exploration activity also plummeted.

During the 1990s, the total number of exploration wells drilled per year dropped to below 50 in 1999 from around 220 in 1990 (Fig. 4).

The slight exploration rebound during 2000-02 was mainly buoyed by bullish oil prices, but it was clear that exploration boom times were in the past. Not only did exploration follow the downslide of discoveries, but so did asset deals in the North Sea. Edinburgh energy consultant Wood Mackenzie found out that the number of such deals "fell from a high of 156 in 1997 to 104 in 1998 and only 54 in 2002."22 Furthermore, "the value of asset deals dropped from a peak of $11.9 billion in 1999 to $7 billion in 2002"—yet another sign that the overall decline had set in.

And BP's January 2003 sale of its interest in the Forties oil field to Apache Corp. is a fitting sign that the North Sea was not what it used to be.

Consequences

Among the major oil producers outside the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, the North Sea was one of the major pillars (besides Russia) with roughly 14% of non-OPEC output. But while Russia has been able to stabilize its oil production (mainly due to its "lost" production of the early 1990s) and hopes to plateau at 7.5-8 million b/d in the years to come, the North Sea seems to have passed its peak.

And there is no replacement for the North Sea's declining output. For those hoping that the Caspian Sea will take up the slack, they will still have to wait for the verdict on Kashagan and other Azerbaijan hopefuls.

The North Sea decline is yet another example supporting the global oil depletion theory (OGJ, July 14, 2003, p. 18), coming on the heels of Alaska's decline. But its decline will have some major consequences for all players in the global petroleum industry.

Globally speaking, the gradual loss of a major province will further place pressure on an uncertain supply picture.

In addition, for Europe and the European Union, the diminishing output from a highly secure and reliable region—which accounted for some 92% of its domestic oil production—cannot fail to have momentous consequences.

First and foremost, it will lead to a widening gap between Europe's production of 7 million b/d and its 16 million b/d of consumption—thus gradually leading to a ramp-up of imports and resulting in a heightened dependence on the former Soviet Union (whose oil exports to Europe amounted in 2001 to 78% of its total oil exports) and on the Middle East (creating competition with other customers such as the US, Japan, and China).

Finally, Among the five North Sea producers, the transition will prove most difficult for the UK. According to present projections, the UK should switch in 2005 from being an oil exporter to being a net oil importer: a drastic change after 3 decades of exports. Norway will be in a far better position with her oil exports predicted to continue for the foreseeable future, and with her natural gas exports gradually ramping up.

For the other three (i.e., Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany) declining oil output will have minimal impact, as their production was always limited.

Perspective

The North Sea is both half full and half empty. It is now clearly at midlife, with a good chance of declining gently.

The 1996-2001 bumpy production plateau fluctuating at 6-6.4 million b/d clearly signaled the peak of North Sea production. For most of 2002, production figures have consistently been below 6 million b/d.

The question now is not to stop the inevitable decline, but rather to hope to reduce the slope of the falling output to any extent possible.

In any case, the North Sea oil output decline is not only yet another sign of general oil depletion worldwide, but also a pending problem for Europe and the European Union, which will witness their oil dependency increasing in direct proportion to the region's declining output.

Such a consequence will send ripple waves throughout the global oil industry and lead to an overall reshuffle in all major regional supply-demand equations.

References

1.Facts 2002—The Norwegian Petroleum Sector, March 2002, p. 13, Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy.

2.North Sea Developments, Drewry Shipping Consultants, London, January 1984. However, these were not the first discoveries. The first NCS find was Balder field (1967), and on the UKCS, the first was Arbroath field (1969).

3.North Sea production statistics differ slightly, depending on the source. For these record years, the main sources were: for UKCS, various issues of Petroleum Review; for NCS, Norway's National Petroleum Directorate (NPD); for Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany: issues of both Petroleum Economist and Petroleum Review.

4.Among others, Werner Zittel, "Analysis of UK oil production," February 2001, at www.energiekrise.de.

5.Petroleum Review, March 2002, p. 29.

6.Ibid., September 2001, p. 2.

7.Brower, Derek, "Tax and be damned," Petroleum Economist, July 2002, p. 26.

8.Fletcher, Sam, "UK hits offshore producers with supplemental tax," OGJ, Apr. 29, 2002, p. 30.

9.Petrostrategies, Dec. 9, 2001, p. 7. Also see "In the UK 2003 budget, the Petroleum Revenue Tax was abolished effective Jan. 1, 2004," Petroleum Review, May 2003, p. 10.

10.Crook, Jeff, "Satellite Accelerator initiative opens window of opportunity," Petroleum Review, March 2002, p. 25.

11.Skrebowski, Chris, "North Sea—entering the end game," Petroleum Review, September 2001, p. 17.

12.Ibid., p. 27., derived from the Wood Mackenzie multiclient study Global oil and gas, risks and rewards, cited by Jeff Crook (note 10).

13.Campbell, Colin J., ASPO Newsletter 20 (August 2002); www.energiekrise.de.

14.Weekly Petroleum Argus, Dec. 23, 2002, p. 6.

15.On this subject, see the excellent reports issued by NPD, among others its Offshore Norway 2001 annual report, Stavanger, March 2002.

16.NPD, The Petroleum Resources on the Norwegian Continental Shelf 2001, Stavanger, July 2001, p. 30.

17.NPD, Offshore Norway 2001, op. cit., p. 11.

18.Quinlan, Martin, "The late arrival at the North Sea ball," Petroleum Economist, June 2002, p. 30.

19.Ibid., p. 30.

20.Platts North Sea Letter, No.1366, June 19, 2002.

21.RWE-DEA AG web site at www.rwedea.com; also, Producing Oil at Mittelplate (December 2001), report issued by Mittelplate Konsortium, a 50-50 venture of RWE-DEA and Wintershall AG. Moreover, since 2000, an additional 10,000 b/d crude oil is being produced at Mitteplate from the onshore Dieksand location (linked to the field by five horizontal wells with reaches of 7,700-9,000 m).

22.Wood Mackenzie gathered these North Sea figures in an exclusive research project for Financial Times, Nov. 25, 2002, p. 20.

The author

Ali Morteza Samsam Bakhtiari (www.samsambakhtiari.com) is a senior expert in the corporate planning division of National Iranian Oil Co., Tehran. He specializes in questions related to the global oil, gas, and petrochemical industries, with special emphasis on the Persian Gulf and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Formerly, he lectured on design and economics at the chemical engineering department of Tehran University's Technical Faculty. He holds a PhD in chemical engineering from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology at Zurich.