Assessing competitive scenarios for the new UK North Sea playing field

BP PLC's divestiture of its Forties field assets to Apache Corp., as well as the sale of its interests in several southern North Sea gas fields to Perenco PLC, essentially launched the formation of a new industry structure in the UK North Sea (OGJ Online, Jan. 20, 2003).

Other majors are following suit, and the role of the larger companies in the region appears to be shrinking.

How will asset divestitures of the majors affect the competitive landscape in the UK North Sea?

Through simulation and the creation of four scenarios, this article assesses the potential characteristics of the new environment in the region.

Specifically, the article will show that:

- There is substantial value to be had by an appropriate set of stakeholders investing in UK assets. PFC Energy estimates that the potential value additions to the UK oil and gas industry could be £1.7 billion. This figure is in addition to an estimated existing value of £5.9 billion assigned to approximately 120 fields with return on capital employed (ROCE) of less than 15% under a base-case scenario. These figures do not include the benefit to the UK government.

- High rewards in terms of net present value (NPV) are not necessarily commensurate with high ROCEs. Therefore, smaller oil and gas companies that can focus on NPV generation rather than ROCE as a performance metric are likely to pursue more of the opportunities with NPV upside.

Background

Some companies are struggling to meet targets even though prices have been high.

This struggle will be tougher if oil and gas prices fall, particularly for companies with significant production from a relatively high-cost basin with modest returns such as the UK North Sea.

For the majors in this position, maintaining competitive returns under these circumstances will be difficult because of their scale, and many of them see better returns and performance gains in investments outside of the UK. Is there a way for companies to inject additional capital into these UK investments that is commensurate with competitive performance targets in their peer class?

Recent acquisitions by Apache, Perenco, and others are obviously one of these ways. But how far can this go?

- What is the potential to the UK North Sea of a different industry structure consisting of various sizes of independents injecting new capital?

- Is there a limit to this growth, and will there be different classes of new entrants into the UK?

Scenario assumptions

For brevity, this article concentrates on two performance measures: NPV and ROCE. Note that ROCEs shown are an average over 2003-05 and are for individual fields only.

ROCE is by its nature a short-term measure, and it may be possible that ROCEs in later years will be much higher. This is certainly the case for many of the assets, which means that there may be additional value to companies prepared to sacrifice ROCE performance in the short term for a longer-term improvement in this measure.

The simulations assume performance gains from Jan. 1, 2004. We have used a flat nominal oil price forecast of $20/bbl and current UK gas prices in all of the simulations.

Of course, with higher or lower prices the NPV and ROCE estimates could vary significantly.

Opportunity set for new players

There are currently 350-400 assets either producing, under development, or being considered for near-term development in the UK.

In the analysis that follows, we have used a simulation model of the UK oil and gas industry to investigate the potential impact of a future industry made up of a larger base of smaller players.

Our estimates indicate that around 35% of the UK portfolio (120 fields) is likely to yield an ROCE of less than 15%. As this is typically the ROCE target used by the larger players, we have assumed in this analysis that all these assets would be targeted for sale, although this may not be the case.

As seen in Fig. 1, these target assets in aggregate have a current value of around £5.9 billion after tax and a range of ROCEs.1

It is not the intention to analyze these assets in detail, but to use scenarios to investigate potential outcomes. We have therefore created four example scenarios as follows:

- Scenario 1: Cost reductions only. We have assumed that companies will obtain a consistent reduction in operating expenditures and capital expenditures of 10%/year over the next 10-20 years. We believe this will be a tough target but use it as a stretch target. No other benefits are assumed.

- Scenario 2: Cost reductions with increase in production. The same as Scenario 1, but assumes that 5% additional reserves are extracted from the reservoir. This scenario includes additional drilling costs.

- Scenario 3: Cost reductions with increase in production. As with Scenario 2, but with 5%/year cost reductions and 2.5% increase in reserves.

- Scenario 4: Tax changes or other incentives. Tax changes can be used as a virtual form of capital injection. It is not our intention to show the merits of these but use a 20% reduction in corporation tax as an example. The benefit is applied to target assets only.

Results from simulations

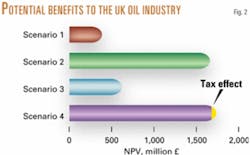

Fig. 2 clearly shows that there are substantial opportunities for value creation resulting from changing the structure of the UK North Sea (assuming the benefits simulated).2

These benefits equate to an additional 29% over the current base value of the target assets.

Note that the tax benefits are only those associated with the target assets that were uneconomic under current assumptions. This benefit is small and has been added to Scenario 2.

A 20% Corporation Tax reduction applied to all "target assets" would have yielded an additional £850 million of value.

It is likely to be difficult to capture many of these benefits for a variety of reasons, including:

- Sales packages may include underperforming assets, which may drag down the overall gains.

- Companies may not sell assets.

- Projects may get delayed.

- Benefits may not materialize as detailed.

Whatever the degree of value capture, a close examination of a best-case scenario, i.e., Scenario 2, reveals that many of the assets are low-return and yield limited incremental value on an individual basis.

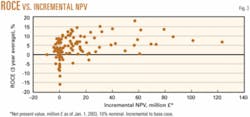

Fig. 3 plots the incremental NPV gains from the cost reductions and reserves increases against the ROCE that would be achieved through cost reductions and reserve increases.

Benefits can be large, but even after the addition of the benefits, 80% of the assets still would earn less than an 8% ROCE.

Only a handful of the assets would then earn a ROCE of around 15% or more.

What does it all mean?

There appears to be a number of issues that can be distilled from this analysis:

- Although many of the assets could provide substantial NPV rewards to smaller companies, the ROCEs are low. Will the analyst community allow this and forgive these companies for developing these assets?

- There are very few of the target assets that the larger oil companies could potentially improve and keep within their portfolios. Of course, these may also be targets for the larger independents.

- Tax changes could help to increase some of the returns of these assets to more acceptable levels.

The tax scenario simulation showed that an additional 20% of the fields produced in excess of 12% ROCE over the Scenario 2 case. The incremental NPV associated with these fields is of the order of £820 million. This may be difficult for the UK government to justify.

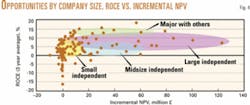

To illustrate how the scenarios might influence the competitive landscape in the UK North Sea, we have attempted to show in Fig. 4 how different classes of companies will divide the potential benefits of the target assets.

Our classification has been divided on the basis of ROCE acceptability. That is, we have assumed that smaller companies will have more leeway to concentrate on NPV gains rather than ROCE performance. This is less likely to be so with larger competitors.

Remember too that the target set represents only about 50% of the total UK asset portfolio.

Conventional players could probably remain large players even in a mature environment, but this will likely change over time.

Summary

The simulation of the UK oil and gas industry using four scenarios appears to show that:

- There are still opportunities for major oil companies to play in this market and to aid in meeting their wider corporate targets, albeit in a limited way.

- For smaller companies, the opportunity set is much larger, especially for those that place less emphasis on ROCE as a performance metric. Assuming these companies are able to fund growth, they can acquire UK North Sea properties with NPV upside without having to weigh heavily the ROCE implications.

- Surprisingly, only a small number of the "target assets"3 will meet a 15% ROCE target after investment and cost reductions according to the different scenarios.

- With the appropriate investment, approximately £1.7 billion of value could be available to UK oil and gas players (plus an additional amount available to the UK government through taxes).

References

1.NPV at Jan. 1, 2003, 10% nominal million pounds sterling; ROCE averaged over a 3 year period; assets with <15% ROCE; $20/bbl oil price assumption.

2.Assumes no project delays or excessive premiums paid for the assets. The NPV represents the additional NPV generated by the scenarios over the business-as-usual case.

3.Target refers to those assets that we identified as currently earning less than 15% ROCE over the next 3 years.

The author

Gary Howorth (ghoworth @pfcenergy.com) is a director in the Corporate Advisory Group with PFC Energy based in Washington, DC. He has some 21 years of industry experience in the oil and gas sector, including 10 years with BP PLC. His experience includes all aspects of the oil and gas business worldwide, from risk management to exploration to refining operations. Gary graduated from the University of Southampton in 1982 and the University of Strathclyde in 1990. He is a chartered engineer (MIEE), a member of the Institute of Petroleum, and has an MBA.