What can a government do about energy conservation? What SHOULD a government do about energy conservation? With worry high in the US about elevated prices of natural gas, with dependency on imported oil rising, and with political campaigns revving up, these questions need constant attention. What governments do—or at least threaten to do—about energy conservation usually is wrong.

Energy conservation holds nearly universal appeal. It should. Energy conservation is a law of nature. And the laws of economics cooperate nicely by providing constant inducements, which strengthen when supply comes under strain and prices rise. This is happening now in the US with natural gas. Conservation is a proper and natural response. It shouldn't be a political response.

Energy peculiar

Political attention turns most seriously to conservation when energy prices rise to levels consumers find distressing. In this, energy is peculiar. When bread prices rise, politicians don't feel obliged to make people eat less bread. Alas, energy-price discomfort creates an audience for politicians eager to capitalize on energy conservation's widely embraced righteousness. The problem is that politically imposed conservation can work only by aggravating the condition that inspires it.

Governments impose conservation in one of two general ways.

One way is to set limits on the use of energy, usually of some specific form of energy. This never works. The most sophisticated energy-use limitation, and the one with most intuitive allure, is the targeted efficiency mandate. In this category belong fuel-economy standards for automobiles. Efficiency mandates accelerate commercialization of technologies reducing the amount of energy required to perform some quantum of work. This would indeed lower total energy consumed if work were constant, which it is not. Lowering energy intensity lowers the marginal cost of performing work, which encourages work. Owners of new, fuel-efficient vehicles have more incentive to drive than do drivers of old fuel guzzlers because their costs of driving extra miles are lower. An imposed cut in gallons of fuel consumed per mile driven thus raises the number of miles driven, failing to deliver all or any of its promised reduction in total gallons consumed.

The way to impose energy conservation that works is to raise taxes on energy consumption. Consumers facing elevated costs cut consumption. But costs usually are high already when politicians feel the need to impose conservation. New taxes thus intensify existing pain. They also stay in effect after the market reverses and prices fall, ensuring that the pain lasts. Markets do eventually reverse unless governments intrude.

So governments can impose conservation successfully but not painlessly. And by the time they get around to imposing conservation, market responses nearly always have eased prices and thus the compulsion to act.

Should governments act anyway? Is energy conservation so rich with civic goodness that governments should impose it at every opportunity?

No. And the answer is not because conservation lacks civic goodness but because government imposition does.

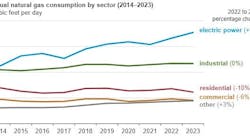

If people see value in energy conservation, they will pursue it on their own. In fact, people apparently do see value in energy conservation and pursue it without prodding from government. They pursue it in response to natural economic incentives to avoid cost. The vigor of the pursuit increases as energy prices rise. This is partly why the amount of energy required to generate a unit of growth in advanced economies declines over time.

Conservation thus happens naturally where markets work. Why, then, would any government want to interfere with markets by imposing something certain to happen anyway and with less economic pain?

Urge to rule

In fact, as a pure matter of democratic principle, they should not impose conservation. The urge to do so grows out of the urge to rule individual behavior, which in a free society should forever and systematically be resisted. Diehard conservationists argue that energy conservation effected by rewards for cost reduction isn't enough. By what standard, though? How much conservation is enough? Answers to those questions properly come from free people making decisions they think best, not from politicians pretending to know better.

What a government can do about energy conservation, therefore, and what a politically charged government anxious about gas supply should do now, is let the market work. Just let the market work.