Libya: Energy investments persist in a puzzling land

Libya1 is an underexplored, underinvested, underestimated, risk-filled, yet opportunity-laden country. Trying to figure out how and why certain decisions are made is sometimes akin to figuring out the Churchillian "riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma."

This is a country that seems very much locked in the time of Nasser's Egypt (1952-70) in economic policies but with the added constraints of the political and social policies based on the Green Book of Muammar Qadhafi.

It is also a country of changing business goalposts, flexible rules, and delays. It is not exactly unexpected that contradictory political and other signals might emanate from Libya on a regular basis.

Even with Qadhafi's seemingly changed views toward the west and "revolutionary movements," he still sometimes publicly admonishes the west. On a very important issue, the Lockerbie case, he once stated that the US should pay some of the compensation. At another time, his son Seif Al-Islam, stated that Libya must pay the compensation but that Libya was not responsible. ILSA and other US sanctions will not be lifted without a full admission of guilt and a full and timely compensation of the 270 victims of the Lockerbie tragedy.

Employment issues

This is a country about the size of Mexico that has only about 5.3 million people. It has a 30% unemployment rate, yet it imports hundreds of thousands of mostly African and Arab workers.

The domestic labor force is growing at 3.4%/year. The number of jobs produced does not even approach the number of new people on the labor market each year. With over 45% of its population under 15 years old, this will become far more important in the future.

About 70% of all salaried Libyans work for the government. There are limits to what the government can offer them in the future. Considering that 87% of Libyans live in urban areas, unemployment could be a source for real trouble in the future. The growth of opposition groups, as well as the anti-African riots, could foreshadow future difficulties.

Oil and gas

Libya, an OPEC member, has proved reserves of about 35 billion bbl, but its National Oil Co., which is effectively the Ministry of Energy, states that there may be as much as 117 billion bbl of oil.

This is a debatable estimate, but one must remember that 70% of Libya's territory is not explored, so there might be a lot more than 35 billion bbl.

Libya produces 1.3 million b/d. In 5 years it hopes to be up to 2 million b/d. It is inexpensive, as low as $2.50/bbl, to extract the light, sweet Libyan oil.

Libya has 46.5 tcf of natural gas. It may have much more than this. Natural gas is even less explored and invested in than oil.

Fiscal balance

Libya is underdiversified as well. About 95% of its export earning, $11.3 billion recently, comes from oil exports. Some 30% of its GDP of about $35 billion comes from oil. About 65% of its government receipts comes from oil. Its GDP per capita of about $6,500 is the highest in Africa, but the country is underdeveloped for its income level.

GDP per capita, as well as government budgets, depend heavily on the price of oil. Libya's GDP per capita has been mostly declining over the last two decades. Libya's budget has been under strain due to large construction projects, like the Great Man Made River, and the fact that it needs to import 75% of its food.

It also has foreign debt payments on its $4 billion debt, mostly to Russia. However, Libya has an interesting way of solving budget deficits. It extracts from its foreign exchange reserves, now $14.6 billion or 15 months of import cover, to balance the budget.

Foreign direct investment has not been even near what it should be for a country so close to Europe, with an educated population, and with a pile of oil and gas.

Libya's human development index is the best for Africa and above average for the Arab world. But one can wonder what Libya might have been like if less of its money was spent abroad and for other people's problems.

Climate of delay

As senior political consultant George Joffe once said, "Everything in Libya is political." Many decisions that investors need to have done well, and done quickly, seem to be mired in politics, bureaucracy, and the confused nature of Libyan government administration.

Also, "the people," otherwise known as the government, run almost all businesses. However, Libya is effectively a military dictatorship run by Qadhafi and his close associates, sometimes known as the "Gang of Five," his family, his tribe, and other assorted permanent and temporary hangers-on.2

Many investors complain of slow payments, as do government workers who sometimes wait long periods to get their salaries. Delay is a key concept to live with in Libya: delayed payments, delayed contract agreements, delayed legal changes, delayed spare parts, and more. Patience and endurance are needed to succeed in Libya.

Sometimes decisions that may seem final are changed in mid-stream, canceled, or simply held in limbo. A recent case in point for oil and gas industry investors is the much touted, but much delayed, new hydrocarbons law. No one seems to know what stage it is in, although some have mentioned that it is to be passed "sometime in 2003."

The General People's Council (the rubber stamp "parliament" of the people) has yet to meet on this. But, in a creative way, many of the changes in the laws have already been incorporated into NOC's Exploration & Production Sharing Agreement Version 3 (EPSA-3) contracts.

The recent moving of the NOC to Ras Lanuf also caused some confusion. During the move some important contacts in the NOC did not have telephones or even offices. Many of the problems associated with the move seem to have been solved, but this is still another example of why being patient and flexible is so vital in Libya.

Other problems

All businesses in Libya must have majority Libyan ownership, for example.

Tax law is not transparent. Taxes are often on deemed income rather than book income. Agency laws can also be problematic, especially if one tries to cancel an agency contract.

Investment rules and regulations can sometimes be selective and arbitrary. There are strict labor laws, including a minimum and required 24 workday holidays and a requirement that to import labor a company has to prove that there are no Libyans that can do the work. It can also be very hard to fire Libyan workers.

Another labor problem in Libya is a severe shortage of highly skilled workers. Libya has one of the highest literacy rates in Africa, 70%+, but its economy gives almost no incentives for its people to acquire and develop important skills.

Personal income tax rates are crushing. They top out at an astonishing 90% for incomes over 220,000 Libyan dinar (LD)—the dinar is about 1.5 to the dollar on the black market—and are very high even for those making over 6,000 LD.

Government salaries have been fixed in nominal terms since 1981. So they have been on a downhill slide in real terms since 1981.

Yet more and more people work for the government because there is no real legal alternative. Tax laws, and rates, steer most people away from the private sector, as do the stifling import and trade restrictions (also often opaque and unpredictable).

Other considerations

Corporate tax rates are very high as well, topping out at 60%. Tunisia's top rate is just 35%.

Also, the typical Libyan entrepreneur also has to deal with "revolutionary committees" and "purification committees" that sometimes either take it upon themselves, or are ordered from above, to "combat corruption." Once recently they got so out of control that the leadership sent out "volcano committees" in order to quell the zeal of the "purification committees."

Telecommunications infrastructure is in need of improvements. Public enterprises are mostly in poor shape. The financial and banking infrastructures are in terrible shape.

The banking system is anachronistic to say the most. Many foreign investors stay away from it. They use banks in Malta, Tunisia, or elsewhere. The banking system is also all in the public sector and controlled by the Central Bank of Libya.

Most financing, such as a letter of credit, needs to be found outside Libya, and that will sometimes be very difficult because of the risks involved in investing in Libya. There is a lot of talk about modernizing and improving Libya's banking system, but that cannot be done in a vacuum. There are so many other things that need to be changed and reformed.

Positive signs

A good sign is the appointment of Dr. Shukri Ghanem to be the Minister of Economy and Foreign Trade.3 He served a short time before being appointed Prime Minister in late June.

Dr. Ghanem has a PhD from Harvard and has worked in OPEC and in other international organizations. He seems to understand how proper economies should work and how Libya needs to change in order to use its wealth properly.

One hopes that Dr. Ghanem and others, like Basjir Zenbil of the Libya Foreign Investment Bureau (LFIB), Abdel-Hafez Zleitni, chair of NOC, Lajili Adelsalam Brini, minister of finance, and Taher Al-Jehaimi, head of the Higher Planning Council, can help pave the way before they are shifted to other jobs or sent overseas.

One of the changes toward reform and away from a multiple exchange system occurred when the LD was devalued by 51% in January 2002. This brought the official rate close to the market rate for the time being. There is yet a third commercial rate that is very different from the other two. There was talk of unifying the rates, but that idea seems to be now on hold. Every other country in North Africa has unified its exchange rates.

Oil investments

Even with all of these risks, and the Australian Trade Commission puts Libya at an investment risk of 5 (out of 6, with 6 being the highest risk level), some hearty and courageous investors have come to Libya to profit from its oil and gas.

Consider, for example, the extensive new blocks, over 135 of them, offered by NOC in 2000. Very few have been contracted out yet, but some of the blocks could hold significant finds within them.

These new block offerings brought in new investors like the BG Group, Royal Dutch/Shell, Teikoku, Itochu, and Edison Gas of Italy. Long time investors like TotalFinaElf, ENI, OMV, Repsol YPF, Wintershall, Norsk Petroleum/Saga, Veba, Lundin, Saipem, Hyundai, China Engineering Petroleum and Construction, Pedco, Red Sea Oil, Petronas, Nimir, and others also showed great interest.4

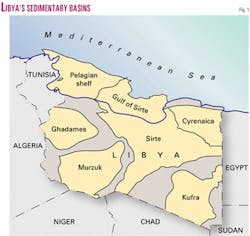

Overall, Libya also is in dire need of foreign investment and foreign expertise to help repair, maintain, and expand its oil and gas industry. Some non-US companies are willing to help Libya develop its industry and are increasing their interests and investments in Libya. For examples, along with other contractors, Repsol is developing the Murzuk basin; Total is developing Murzuk; and Petro-Canada is developing En-Naga, which includes the large Amal field in the Sirte basin (Fig. 1).

ENI is developing Elephant field, which could have 1 billion bbl, even with significant delays and other problems. Contractors like CCC and J&P of Athens, Technip-Coflexip, Snamprogetti, and MAN are also involved in the development of Elephant.

Other projects

There are some major refinery projects also on line in Azzawiya, Tobruk, Zawya, and Sirte. These are mostly being developed by coalitions of many companies from the EU and East Asia.

ENI is also a major player in the huge, multibillion-dollar Western Desert Project. JGC of Japan, Tecnimont, Sofregaz, Hyundai, Saipem, and others are also involved. This includes developing Wafa gas field, pipeline projects, and a processing facility in Melitah.

Gas customers for the project are already being set up in France and Spain. Other gas projects are in the works. Many of these are also in response to the new EPSA-3 contracts that now allow exploration and production of natural gas. Previous EPSA contracts were for oil only.

A $5.6 billion pipeline to Sicily is also being developed with ENI as a major player. Bouygues and Agip Gas BV, and Doris Engineering are part of this. This is part of Libya's overall goal of being itself a major player in EU gas markets. So far all of Libya's gas exports are LNG to Spain.

Intercountry plans

Egypt and Libya have agreed to build pipelines linking their countries' natural gas and oil transportation networks. Libya and Egypt have also set up a joint oil and gas company. Libya has taken the place of Israel in the development and running of the Midor refinery near Alexandria.

Libya has also set up joint ventures with Tunisia (ETAP) and Algeria (Sonatrach), which could prove to be very important linkages for Libya, especially the Tunisia link across gas and oil fields to the Gulf of Gabes and on to the EU. Such oil and gas deals have also helped Libya solve some of its border and international relations problems.

Pakistan and Libya have started an investment company, Pak-Libya, that is involved in upstream investments mostly. Libya has significant refinery and distribution investments in the EU, especially in Italy, Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands via OilInvest.

US opportunities

US companies are blocked from doing business with Libya. This will be the case until various internal US laws and regulations are changed.5

There is a US trade embargo on Libya, and US passports are not valid in Libya. Libyan assets are still frozen in the US. There are numerous laws and regulations supporting unilateral sanctions against Libya by the US.

Until the "Lockerbie" issue, the murder of 270 persons in Pan Am 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, in December 1988 is resolved completely, it seems unlikely that the US will back down from the laws and sanctions.

The Libyan government has been holding the assets of the Oasis Group (Conoco, Amerada Hess, and Marathon) and Occidental since 1986 and awaits the companies' return. But recently the Libyan government threatened to turn these assets over to others for development if the American companies did not return soon. Last year the Oasis Group companies were allowed to visit their former assets.

It is also of great interest to note that many of the contracts in oil and gas between Libya and non-US firms are well above the $20 million/year limit set under the US's extraterritorial Iran-Libya Sanctions Act, yet the sanctions do not seem to be enforced.

Many non-US companies may be considering ILSA to be an added risk, but so far it has hardly stopped them from being part of the investment schemes developed since the UN sanctions were take off in 1999.

Libya's role

Libya's oil and gas industries are in need of updating, repair, and further development investments both upstream and downstream.

Libya could be a great source of potential investments. However, there is still a large sense of uncertainty about where Libya might be heading, even with the positive changes that have occurred, such as the suspension of UN sanctions and some important changes in the EPSA contracts.

The mercurial nature of Libyan leadership and the wariness with which world still sees the Libyan government, the Libyan investment and "legal" climate, and more make it very difficult for Libya to attract investments in industries other than oil and gas, but that may change if there are significant changes in policies and laws inside the country and outside.

There seem to be some recent movements on the Lockerbie case with the Libyan government accepting civil responsibility. However, this got a somewhat cool reception in Washington it seems. The litmus tests for Washington seem to be that Libya accept criminal responsibility, that it compensate the families of the victims, and that it completely denounces terrorism and support of terrorism.

All opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not represent those of the National Defense University or any other entity of the US government.

References

1. Economic data are often scant and unreliable. They should be considered indicia.

2. The most important group is the "gang of five;" Muammar Qadhafi, Abu Bakr Younis Jabr, head of the Libyan Army; Musa Kusa, head of the Libyan Intelligence Services; Sayf Al-Islam Qadhafi, Muammar Qadhafi's second son; and Abdullah Salem Al-Badri, the vice-premier.

3. Much of the central government was ostensibly abolished in 2000. Curiously, a lot of the power centers were moved to Muammar Qadhafi's home town of Sirte. All ministries not directly tied to foreign affairs were dissolved into the 31 governates, or sha'biyat. What seems to have happened is that even more power is in the hands of Mr. Qadhafi, his family, and others. Luckily for Libya and for investors, Dr. Ghanem's post was retained as a ministry.

4. Please see MEED Weekly Special Report on Libya, Aug. 9, 2002, EIU Country Reports on Libya, and EIA Country Analysis Briefs on Libya.

5. Please see website (www.treasury.gov/ofac).

Bibliography

For further information on the complexities of US-Libya relations, and the possible routes toward cautiously changing that relationship, and the requirements need for such changes to occur, please see Atlantic Council, U.S.-Libyan Relations: Toward Cautious Reengagement, April 2003, found at (http://www.acus.org/Publications/policypapers/internationalsecurity/Libya%20Roadmap.pdf).

The author

Paul Sullivan ([email protected]) has been a professor of economics at the National Defense University since July 1999. For six years previous, he taught and researched at the American University in Cairo. He is also a member of the working groups on Libya, Iraq, and Iran and the Atlantic Council, and the head of the North Africa and Levant Regional Security Study at the NDU. He has a BA from Brandeis University and MA, Mphil, and PhD in economics from Yale University.