Special Report - Marine transportation facilities face new US security regs

Next month, the US Coast Guard will publish regulations based on the 2002 Marine Transportation Security Act (MTSA), which directs compliance with international treaty obligations formulated by the International Maritime Organization.

The IMO's Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) conventions have established security requirements by adding Section XI-2 that adopts a new International Ship and Port (Facility) Security Code.

SOLAS signatories, of which the US is one, commit to bringing their maritime industries into compliance with the ISPS code by July 2004. By yearend 2003, affected US facilities must complete their planning to provide time for the Coast Guard to review those plans by the July 2004 deadline.

Given this aggressive timeline and the relative newness of the subject, a significant number of facility planning personnel likely will seek the support of consultants to fulfill their obligations under MTSA.

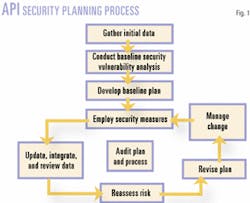

Recent publications by the American Petroleum Institute (API), such as the Security Guidance for the Petroleum Industry, have identified a process (Fig. 1) that is likely to be followed by many of those responsible for compliance with these new regulations.

Initial data gathering

Data gathering actually consists of a subset of actions performed in the API security vulnerability assessment (SVA) process. In application, it also serves as a strategy development phase in which goals and objectives are developed following an initial assessment of needed data (plans, procedures, security reports, security equipment rosters, and training and exercise systems).

Questions for the designated leader to consider for this phase include:

1. What are and who performs security activities at the various operational levels? Who would best represent this group in identifying the role of existing security providers in the execution of the process?

2. Who holds the documents related to security, and what types of information exist?

Possible items needed include emergency response plans and procedures, incident and suspicious-activity reports; facility operational plans and drawings; security equipment rosters; lists of security personnel; role and responsibility descriptions for these people and others whose responsibilities may evolve to include security; and training or exercise program descriptions as they might relate to security training exercises.

3. Is the organization's security provider (security) prepared to play a role in the security planning process and to what degree? Are the organization's personnel prepared to lead or perform tasks within the system? What level of commitment (in hours per week) can security commit? How does security or the organization see security contractors being used in the process?

Possible scope elements associated with this phase include:

- Assembly of security-related documents.

- Review of security-related documents.

- Development of a needs list of items to be addressed in preparation for SVA.

- Development of a strategic plan for completion of the MTSA security development process, including milestones and schedule.

Baseline SVA

After the data-collection phase needed for the SVA process is accomplished, the next phase includes remaining pre-field activities, identification of facilities that warrant a formal SVA, execution of the "ground truth" (field visit) activities, and development of recommended improvements following field activities.

The designated leader should consider a number of questions:

1. Cost benefit. What criteria does the organization think are critical in developing an initial shakeout process by which it can rank facilities according to the greatest need for a formalized SVA?

Factors identified by API and other sources include the level of effect an incident would have on personnel and the asset and the effect of an event on the environment surrounding the asset and the organization's reputation.

The SVA team or contractor will be asked to evaluate facilities and scenarios at breakpoints in these factors. These breakpoint values will affect the number of facilities requiring SVA and the level of funding needed for this activity. This is critical for the leader to control the process.

2. How significant to the organization is due diligence, and what level of funding does the organization want to commit to documenting the SVA process?

3. Does the organization wish to commit to a particular SVA methodology?

Possible SVA methodologies are those developed by API or the Center for Chemical Process Safety or other processes such as Sandia Laboratories' Vulnerability Assessment Model (VAM).

The organization can either send personnel off site to be trained or hire a trained (and in some cases licensed) contractor to perform these services on site. It should be noted that all processes identified to date are highly subjective, despite the effort to make them objective. This is significant in that any SVA-VAM analysis may result in an output that may fail third-party auditing.

4. How will the organization handle or hold security-sensitive information such as the documentation of the shakeout process and the output from any SVA?

Possible scope elements associated with this phase include:

- Performance of facilities shakeout ranking, using factors and breakpoints established by the leader, with documentation of the process to demonstrate due diligence and auditing by the US Coast Guard, industry audit teams, or a corporate oversight group.

- Documentation of any existing shakeout ranking process and other general security improvements that have been accomplished to date, particularly those since Sept. 11, 2001.

- Finalization of SVA steps leading to the ground-truth process, including threat scenario development, preliminary evaluation of selected assets, customization of ground-truth forms to selected assets, organization of the field team, and preparatory briefing of field team members.

- Having the field team commence the ground-truth process at the selected assets, including interviewing security, response personnel, and selected operational staff to complete customized forms.

- Conducting of a post-ground-truth debriefing in which facility management and the field team review the preliminary evaluation and determine how it was changed by the ground-truth process. The debriefing should include a preliminary review of improvements identified by the field team and a discussion of which improvements are warranted (a cost-benefit issue).

- Performance of this step close to the facility and immediately after performing the ground truth will prevent unreasonable suggestions from becoming codified in reports.

- Develop and deliver a final SVA report that includes documentation of the products resulting from the preceding steps.

Baseline plan

In the baseline phase, a security team composed of the organization's operational elements, the emergency-incident response elements, the security structure, and a plan development contractor (if needed) proceed to develop an organizational security plan from an outline, lists of scalable actions, rosters of communications equipment, and personnel capable of filling roles as MTSA security officers.

One possible starting point for the security plan is the emergency response plan, as the similarities between the 1990 Oil Pollution Act and MTSA are obvious. Sources of text for the plan could include industry guidance documents, as well as the Coast Guard's Navigational and Vessel Information Circulars (NVIC) 10-02 (vessels) and 11-02 (shore facilities). The Coast Guard has yet to release an NVIC specific to offshore facilities and may not, given the speed of promulgation.

At a minimum, plan on two to five meetings of a planning team composed of the designated leader and the organization's operational, incident response, and security components. They will work to develop the plan or to provide input on the organization's existing security processes to direct a contractor properly, if one is used.

null

The designated leader should consider these important points:

1. Who in the organization should staff the planning team?

Enough participants with the proper level of authority should be identified to focus the direction and scope of the document from a conceptual outline through population of the outline with appropriate concepts and asset-specific, scalable actions to the final draft.

As the document nears completion, the size and scope of the group should be increased to ensure organizational agreement.

2. What level of commitment (in hours per week) can these planning team members give to develop this document?

3. Who will lead the team so that sufficient authority exists to bring team members to the review table when they have conflicting obligations?

4. Does the organization want a single overall plan applicable to all assets or several plans individualized to specific assets?

Possible scope elements associated with this phase include:

- Development of a plan outline.

- Development of scalable actions for personnel and assets.

- Development of the security plan.

- Facilitation of planning meetings.

Security measures

Included in the employment of security measures are such activities as development of asset-specific procedures, training of personnel in their MTSA-specific duties, development of information dissemination materials (signs, e-mails, fliers), and development and execution of drills and exercises intended to test the newly created security plan and structure.

Questions for the designated leader to consider include:

1. Does this phase need to be initiated or completed before submission of the plan to the Coast Guard?

2. How does the organization accomplish its training, including drills and exercises?

3. Should the MTSA training and drills and exercises be developed separately or as part of the existing incident response program?

4. How does the organization routinely disseminate information about compliance? Who develops these materials? Is he or she available to assist with MTSA-related material development?

Possible scope elements associated with this phase include:

- Development of sample procedures.

- Adaptation of procedures to include MTSA considerations.

- Development of MTSA-related training or components to add to existing training programs.

- Participation or complete delivery of MTSA-related training materials.

- Development of MTSA-related scenarios, drill or exercise playbooks, or complete program.

- Execution or participation in roles of facilitator, evaluator, or participant in MTSA-related drills or exercises.

- Development of informational material for use by the organization in the implementation of the security plan.

Review, revise

Updating, integrating, and reviewing data, reassessing risk, and revising the plan comprise steps in a phase similar in scope to each of the first three phases, except that, by this point, the designated leader and original planning team have gained enough perspective and experience through the implementation of the first round of phases that the organization may not need the assistance of a consultant contractor.

This process is interactive with an auditing process (discussed presently), but weaknesses identified and corrected in the auditing process should not minimize this effort.

Questions to be considered at this point include:

1. Should the same persons that developed the program handle the review-revision process in-house? Or, should different persons handle revision processes to prevent engraining (focusing on weaknesses previously identified and corrected that result in a possibly false sense of security)?

2. Should the reassessment or revision team receive training on how to proceed with the process?

3. Is there support or need for contractor support in these services?

Possible scope elements associated with this phase include:

- Training of reassessment team in the vulnerability assessment process.

- Training of audit teams in the inspection and review process.

- Training of planning teams in revision of the plans and procedures.

- Those scope elements identified in the first three phases.

Auditing the process

Independent auditors help break thought engraining (selection of threats and enhancement actions). Many organizational structures have formalized auditing groups that routinely review other compliance-related plans or programs. If this option exists, it would make sense for this group to be the source for MTSA compliance.

Questions to be considered at this point include:

1. Does existing auditing capability exist within the organization?

2. Is this group prepared to assist, and are they interested?

3. Who is responsible for accessing this group?

4. What training does this group need to prepare them for an audit?

5. Would this group welcome or accept support from a contractor?

Possible scope elements associated with this phase include:

- Development of auditing structure and tools.

- Identification of the sources of compliance requirements and auditing approaches.

- Delivery of independent auditing services or support in execution of audits by organizational elements.

- Documentation of the auditing process and its findings.

- Development of corrective action lists relating to audit findings.

Managing the process

Managing the initial development process and the revision process can be time consuming because of the number of participants needed for proper organizational acceptance and the number of phases or tasks likely to be required.

To best evaluate process management, consider these questions:

1. What is the estimated level of effort required to manage the development and revision processes?

2. What other responsibilities does the manager have?

3. What level of support exists within the organization for this person?

4. Does the designated leader of the planning process need additional support in the implementation of each phase, and what level of support (in hours per week)?

5. Does the organization object to support from outside the organization?

Possible scope elements associated with this phase include provision of management support services such as scope development, cost estimation, process documentation, and quality-assurance review.

The author

William Perry is director of MTSA Services for Ecology & Environment Inc. and is a veteran emergency manager and emergency response specialist. He has a BS in chemistry from Southern Illinois University (1986) and has been working in the environmental remediation and regulatory compliance industry since graduation. He is a member of the American Chemistry Society and the International Association of Emergency Managers.