Special Report - Government, industry forge partnerships for security enhancement

The US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), other US government departments and agencies, and energy industry associations are working closely together to provide a greater degree of security to energy industry infrastructure and personnel in the wake of risks presented by continuing global terrorist threats.

The energy industry has been identified as one of the 13 most crucial infrastructures in the nation and has been named specifically as one of the prime targets of Al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups.

To strengthen the security of existing and planned facilities and prepare for meeting the criteria of the US Coast Guard's new security vulnerability assessment (SVA) requirements due out in July, the American Petroleum Institute and the National Petrochemical & Refiners Association have established guidelines and a methodology to assist companies in developing SVAs for site-specific facilities.

In the US alone these include 150 refineries, 100 US ports that receive crude oil, 4,194 offshore platforms, 200,000 miles of pipelines, and 170,000 service stations.

Other associations representing specific sectors and umbrella groups such as the Energy Security Council also have developed training sessions and security conferences throughout the year.

Cooperating in this intense security effort are the departments of Energy, Commerce, and Transportation, plus the US Coast Guard, US Customs Service, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Central Intelligence Agency, Pentagon, Environmental Protection Agency, and Office of Pipeline Safety, among others.

API programs

Last year, 8 months after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the US, API had established an information-sharing program, starting with the government ties it had formed during Y2K efforts in 1999 to bring the industry's computer systems up to date (OGJ, Apr. 22, 2002, p. 24).

During this past year, the organization has expanded that network and established other important programs necessary to industry security.

"When we started after 9-11, we were working with, at the time, the Department of Energy, the sponsoring agency," said Kendra Martin, API chief information officer and head of the API security team in Washington, DC.

"After trying to sort out what we needed to do and what the government wanted us to be doing, we came up basically with a three-part, three-pronged program," she said.

The program consisted of establishing security guidelines, developing an SVA methodology, and creating a program of information sharing.

NPRA also has been active in making member refineries and petrochemical plants as secure as possible since Sept. 11, 2001.

"We are trying to help our members cope with security threats," said Bob Slaughter, NPRA president (OGJ Online, Dec. 17, 2002). "We want to keep them on the cutting edge of developments in the security area."

API security guidelines

The first arm of the API program, which was an immediate project and what President George W. Bush was looking for from all critical infrastructure sectors, was security guidelines. "In our case it's a comprehensive document that covers upstream, pipelines, refineries, down to transportation (and) distribution," Martin said.

The security guide is a document that helps companies develop security plans and gives them guidance on how to perform a risk assessment for various facilities. It shows how to analyze risks, develop countermeasures in each segment tied to the homeland security alert system, and assess costs and benefits from specific security programs.

When the nationwide color-coded alert (devised by DHS) changed recently from yellow to orange and from orange back to yellow, the industry had guidance on determining how the alert might affect their facilities and companies. That guidance also provided an assessment of the steps personnel should be taking at each of those alert levels, giving the industry a common base and a common language from which to work. "There's also a counterpart piece in the gas sector and the electric sector, and (it) covers the oil industry as well," Martin said.

API developed the document during the winter of 2001, published Version 1 last March, and began immediately writing Version 2, to keep the document evergreen and as complete as possible.

One of the more interesting factors, Martin said, is that the industry is so broad and is regulated by so many different agencies that keeping the documents evergreen and in sync with current regulations is a challenge.

"We have a voluntary program with the Office of Pipeline Safety and so, while the document came out in March, we were immediately working with the various agencies (and) what we were learning within the various companies to update the document." Version 2 of that document was approved by API's security committee Apr. 22 and published by early May.

Documents are published electronically for ease in getting them to the whole industry. "A lot of companies use that to develop their company-specific guides that reflect what's in there," she said.

SVAs

A second part of API's security initiative working with DOE—now undertaken by DHS—was vulnerability assessments.

DOE started about a year ago doing SVA surveys and site visits, working with individual companies and using its national labs and personnel for facility-specific assessments. Working with the government, and looking at security from a counterterrorism perspective, API developed an SVA methodology.

"Out of that work, as well as the work the industry has been doing on its own, we have just completed (an SVA) methodology that is an industry document. Right now the first version of it is focused on refineries. We'll add a pipeline component and others throughout the year, but the SVA methodology is an industry document the DHS will be endorsing as a sector approach," Martin said. "It's been a program that everyone is anxious to participate in," Martin said.

Information-sharing

API's third new initiative has been information-sharing. "We can do all this great security work, but we also have the issue of access to intelligence information (and) threat notification—both government information as well as a greater ability to share with each other," Martin said.

In June 2001, an energy industry Information Sharing & Analysis Center (ISAC) was formed and was just getting started when the terrorist attacks occurred. ISAC operated for about a year as a fee-paid service that was to use subscriber proceeds to help develop ISAC, but participants realized after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks that they needed to find a way to offer it for free across the industry.

Through a grant from DOE-DHS, the ISAC service was expanded beginning in April of this year, and ISAC now offers access to all oil and gas operators who operate in the US, ensuring that necessary government information gets to all of the industry. ISAC also provides an ability for companies to share information with each other, whether it is best practices, incident information, or threats within the industry.

"We do a kind of mix of information," Martin said, "and we're still working on the best ways to disseminate. But there's a growing group of us in the industry that hold security clearances, and we actually have access to classified information. They're doing a lot of work with us to give us more in-depth information than is normally shared," Martin said.

"A secure web-enabled environment really gives us that single focal point that makes it easier for us and gives the government the assurance that they're able to get to the people that they're looking for," Martin said.

FOI vs. confidentiality

ISAC, however, is exclusively for professionals in the energy industries. Because of the need to maintain confidentiality about security programs, no US government agency, regulator, or law enforcement agency can access it.

"They (the government agencies) share with us, but we can't share with them, because we don't want to see (our security information) on the front page of the Washington Post (because of the Freedom of Information Act)," said Bobby Gillham. A former FBI agent, Gillham currently serves as chairman of ISAC, is manager of global security at ConocoPhillips, and is a member of API's security team.

Gillham and other ISAC leaders have been pushing for a better interface with government. "For a couple of years, we've tried to get legislation through the Congress to give us an exemption (from the Freedom of Information Act)," he said.

The pipeline industry made some progress in this area Apr. 2 when the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission initiated a new homeland security program restricting public access to critical natural gas pipeline and power grid infrastructure information other than facilities location (OGJ Online, Mar. 24, 2003). Restricted will be valve and piping detail diagrams at compressor stations, meter stations, LNG facilities, and pipeline interconnections. Also restricted are flow diagrams and other drawings showing volumes, operating pressures, and locations of central gas control centers and gas control buildings, for example.

And, in New York City Feb. 11, during NPRA testimony and comment on the Coast Guard Notice on Maritime Security Docket USCG-2002-14069, William Koch, global director of process safety integrity for Air Products & Chemicals Inc., Allentown, Pa., addressed the same issue as it applies to refinery and petrochemical facilities.

Speaking as a member of the NPRA security committee, Koch asked, "If the Coast Guard conducts a facility security assessment, would the information derived therefrom be kept confidential? (Or) will it be subject to a Freedom of Information request by parties whose interests are not in maintaining security but in publishing the details of our operations to the world?"

Koch said he believes the Maritime Transportation Security Act (MTSA) gives the Coast Guard authority to ensure that the information is kept secure, because Title 46 of the US Code, Section 70103(d), says: "Notwithstanding any other provision of law, information developed under this chapter is not required to be disclosed to the publicU."

Furthermore, Koch said, this position is bolstered by similar provisions in the Homeland Security Act of 2002, Section 214 (6USC § 133), which "provides that information that is voluntarily submitted to the Department of Homeland Security regarding the security of critical infrastructure shall be exempt from disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act."

"Clearly," Koch said, "the intent here is to encourage the submission of security information to DHS with the promise that the information will be kept confidential." Koch urged the Coast Guard to write its regulations with similar strong language to "leave no doubt that the Coast Guard will make the confidentiality of the information it receives a matter of highest priority."

Martin said the confidentiality factor also is instrumental in company participation among members and getting people to talk about what's going on in their facilities.

"And there's just a real struggle between the need for us to really be able to share vulnerabilities and details about what we're doing with each other to help strengthen our program, and yet drawing that line about what the public really needs to know—because of, especially, the internet," she added.

"Look at the sorts of things they've been finding in the caves in Afghani- stan or in the palaces in Iraq. From the other side of the world, there's a pretty good access to an awful lot of information about our facilities."

Mutual cooperation

"DHS is trying to help us with that process, because we have found it very valuable to share with them. Both parties need to have a really good understanding of our operations (and) their threat information, so you start improving our ability to analyze it because that's the real challenge. How do you take the kinds of raw data—strange ideas people might have about vulnerability—and really test them to see 1) if that is as big a vulnerability as you might think and 2) what we can do to mitigate that?" Martin posited.

"We need the government to tell us really what the threat is," said Gillham.

"Yes, a kind of a bigger picture view," Martin agreed. "Sometimes they'll come in and say, 'You know, if I were a terrorist, I'd think this would be one of your bigger vulnerabilities' at a facility, and sometimes our response is, 'God, we never thought of that. We need to do something about that." And sometimes, we'll say, 'So what?' Refineries especially are complicated and sophisticated, so that sometimes what might seem to be a really good target, actually might not harm anything."

It is important she said, for the industry to be apprised of new threats and for the government "to understand what sorts of impact it might have and where it might be of biggest concern."

Overlapping sectors

"Most of the larger companies in our industry are in both the oil industry and the chemical sector, and so we work closely with the American Chemistry Council, which has a program very similar to ours. They have security guidance (and) vulnerability assessment methodology," Martin said. "They have their security Responsible Care (program) code, which is very complementary to API's. DHS has actually taken the work they did with us in the oil sector and are now doing similar visits at chemical plants.

"There are physically a lot of similarities. For our major companies, there's an overlap that causes us to make sure our programs are complementary; they can choose ours or they can choose ACC's. Either way, it puts them in compliance with the programs we've developed."

"It's not only a noncompetitive issue, it's one that's so important to the fiber of our country. You know, we're doing this for reasons far beyond company operational practices or our own interests. And so it does make it easier to work issues like this together in an industry where everybody understands that we have very clear goals of protecting their individual facilities as part of the larger energy network."

"There's nothing proprietary about security," Gillham said.

"As long as it's (kept) within the industry," quipped Martin. "We don't want Al-Qaeda to join the ISAC."

Personnel, responders

In addition to the coordination between API and other energy associations, industry participants have developed partnerships with security officials in the US and have established a close cooperation with local police, fire, and emergency medical officials, as well as outreaches to state and local elected officials.

Many of the federal security personnel now working in the energy industry, such as FBI and Secret Service personnel, know each other and have worked together in previous capacities, Martin said.

"The FBI are the people involved in the prevention," Gillham said.

FBI Director Robert S. Mueller, III, in testimony in Washington Feb. 11 before the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, said that the bureau is beefing up its intelligence operations. "The FBI is undergoing momentous changes —including the incorporation of an enhanced intelligence function," he said. With funding from Congress since Sept. 11, 2001, the bureau has increased total staffing levels for counter- terrorism by 36%, much of it going toward augmenting its analytic cadre and enhancing training for its analytic workforce.

"Despite the progress the US has made in disrupting the Al-Qaeda network overseas and within our own country, the organization maintains the ability and the intent to inflict significant casualties in the US with little warning. The greatest threat is from Al-Qaeda cells in the US that we have not yet identified," Mueller said.

During 1980-2001, he said, the FBI recorded 353 incidents or suspected incidents of terrorism in the US; 264 by domestic terrorists and 89 "international in nature."

"There have been a variety of threats suggesting that US energy facilities are being targeted for terrorist attacks," Mueller said. "Al-Qaeda appears to believe that an attack on oil and gas structures could do great damage to the US economy.

"The size of major petroleum processing facilities makes them a challenge to secure, but they are also difficult targets, given their redundant equipment, robust construction, and inherent design to control accidental explosions," he noted.

Gillham agrees. "We have a very, very robust emergency response planning in place," he said. "For one thing, we in the energy industry are (accustomed to) incorporating and including more state and local first responders (than the average industry)."

In addition, Gillham said: "Most companies today do preemployment screening. And we have a couple of issues there that we're trying to raise with the appropriate legislative authorities. In banking and finance they do it, and that way there was special legislation that was put through a number of years ago to address these serious issues."

"There is a huge responsibility the industry has for their facilities, but our facilities are also impacted by a lot of outside things," Gillham said. "Public infrastructure, bridges, highways, all of that is the government's responsibility. That's why this tight partnership has been so important for our people on the Houston Ship Channel. We rely on the US Coast Guard, even on the National Guard as well as (DHS). What the DHS has been doing is looking at the public infrastructure that is adjacent to and also a piece of (industry facilities) that would have to be protected.

"The Coast Guard has really taken a strong lead in these areas," he added.

Coast Guard's role

The US Coast Guard on July 1 will release the Interim Final Rule (IFR) for new regulations applying to vessels and waterfront facilities, said Robert Schoen, chief of the Coast Guard's intelligence branch in Houston.

"That's basic proceduresUfor waterfront facilities having to conduct security assessments and build plans based on those assessments. The first in the industry to be impacted are waterfront facilities," Schoen said.

After the regulations are issued, industry will have 6 months to comment on them so the Coast Guard can adjust any regulations "that may not make a whole lot of sense or to go ahead and make recommendations on how to improve them," Schoen added. "We need to hear back from the industry," he said, "with feedback on how this partnership effort in homeland security can best improve security."

Feedback also "allows us to provide clarification of any kind of government regulations that are promulgated, so the industry will understand what is expected of them and how they can best comply with these regulations," he said.

"Hopefully, there won't be any surprises associated with the regulations. They will pretty well reflect a document that was put out there several months ago called NVIC11-02 (Navigation and Vessel Inspection Circular) And the title of that is 'Recommended Security Guidelines for Facilities.'

"That is the Coast Guard's way of getting it out to industry early on what we would anticipate the regulations would require of industry, so there are no surprises," Schoen said. "And so they'll understand what needs to be done in terms of an assessment, what needs to be done in the way of enhancing the security of their facilities."

After release of the IFR, companies will have 6 months to provide their security plans—based on SVAs—to the Coast Guard for review and approval. "You're probably looking at December when those plans would have to be submitted to the Coast Guard for review," Schoen said.

The final rule will be issued after the designated comment period.

Protecting ports

Port security is critical for a number of reasons. As many as 14,455 tankers —42% of the world's tankers—called in the US in 2000, said William Gray, president of Gray Maritime Co., at the Mare Forum in Houston last November.

Part of the infrastructure protection program is certifying that ships are not bringing unauthorized cargo into US ports or near critical US infrastructure, Shoen said.

In February Congress approved an outlay of $58 million toward cargo container security to prevent unauthorized elements from being imported into the US via the 6 million containers shipped to the US annually.

The US Customs Service, which has been rolled into DHS, has a number of new initiatives. They now are testing and using x-ray machines and other technology to improve the security of the supply chain from departure points overseas. These can determine if a container has been tampered with, and when and where that might have occurred, Schoen said. The nature of the cargo determines how closely it is examined.

In addition, in assessing cargo being imported into the US, Schoen said, the Coast Guard examines virtually all manifests. They look at port of origin, nationality of the crew, the vessel's last port of call, and "a lot of things that we weigh in the balance to make the determination whether to let the vessel in."

US officials board vessels that are "deemed a high risk for whatever reason," sometimes accompanied by sea marshals, Schoen said. Vessels are boarded further out to sea than before the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks "to put the risk out as far as possible," he said. The US also now requires a 96 hr advance notice from arriving ships, rather than the former 24 hr notice. And Navy vessels are available to provide support when needed, sometimes when transiting within port areas.

As for information-sharing, the Coast Guard, which has a port intelligence team, works closely with joint terrorism task forces, the FBI, and the US Attorney General's office with its antiterrorist task force. In addition, the Coast Guard works with other interagency and industry groups, such as the Offshore Operators Committee, to improve the security of the more than 4,000 platforms and other equipment in the Gulf of Mexico (OGJ, Feb. 4, 2002, p. 28).

RMOTC

In another form of governmental assistance to the industry, DOE has just opened to the industry the US-owned, 10,000 acre, working oil field—US Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3 at former Teapot Dome oil field in Natrona County, 40 miles north of Casper, Wyo. The field can be used as a homeland security testing, demonstration, and training site.

Now known as the Rocky Mountain Oilfield Testing Center (RMOTC), the site includes storage tanks, an operating gas plant on 5 acres, more than 500 working wells, pipelines, vacant buildings, heavy equipment, material, and staff.

The field, which operates around the clock, is available to energy industry companies; municipal, county, state, and federal agencies; and first responder and military units that need a remote site with working oil field equipment to test, demonstrate, evaluate, or train on new homeland security tactics, alarms, technology, equipment, programs, processes, or procedures.

"We also have decommissioned facilities and pipelines that can be used to construct simulators for destructive testing, demolition, and training," said John Woten, the site's Homeland Security project manager.

The field has been used during the past 10 years as a neutral test site, Woten said, where US, Canadian, and UK organizations and companies, such as Sandia National Laboratory, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Schlumberger Technology Corp., Halliburton Energy Services Group, Baker Hughes Inc., BP PLC, and Texaco Inc. have tested new products, inventions, or equipment.

The US government assumes about 20% of costs in in-kind services, such as the facilities, water, electricity, crew, dirt-moving equipment, and operations buildings. In return, the government maintains the right to publish results of the tests and studies for the benefit of the entire industry. Companies wanting to retain all proprietary rights assume 100% of the costs, but the site is still available.

The National Guard, which now is tasked with protecting the nation's gas facilities, also may train there to recognize critical plant facilities, along with police bomb disposal teams, special operations teams, military commando groups, airborne escape and evasion personnel, fire fighting, well control, and hostage-extraction teams.

Continuing threats

"Like death and taxes, terrorist activities are here to stay," Woten said. And two of the most vulnerable elements within the energy industry are tankers and pipelines.

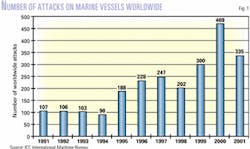

There were 2,375 attacks on marine vessels in 1991-2001 (Fig. 1), with the number of attacks on the increase since 1995, along with the extent of violence associated with them, said Jayant Abhyankar, deputy director of the ICC International Maritime Bureau (IMB). The largest number of attacks are still off Indonesia (OGJ, Apr. 22, 2002, p. 32).

And in the first 3 months of this year, attacks on ships worldwide rose to 103, up from 87 the same period last year, IMB reported.

About 3.6 billion tonnes/ year of crude oil is transported by sea, representing 57% of the world's oil consumption according to the International Association of Independent Tanker Owners.

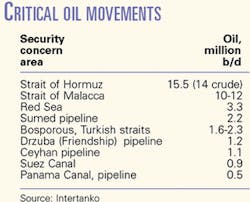

Supplies are most at risk in areas where vessels have been attacked frequently in the past or that present significant choke points (see table).

To avoid piracy and other attacks on vessels, countries that can afford to are increasing patrols, making tanker lanes "no-go" areas for other crafts or, like Turkey, limiting hours and conditions under which vessels may use their waters (OGJ Online, Nov. 19, 2002).

null

To deter piracy, companies are installing nonlethal, electric fences—adapted for maritime use—around their ships, installing more deck lights and employing more deck guards, Abhyankar said. He said IMB is working with a satellite tracking system operator to produce a tracking system, which has been installed on a number of ships, to locate ships at sea or in port.

Pipelines and their personnel also continue to be a primary target for terrorists worldwide, because it is difficult to protect hundreds of thousands of miles of remote facilities.

"This vulnerability to attack is mitigated by the relative ease of repairing pipeline breaks," said Edward Badolato, executive vice-president of homeland security for the Shaw Group and energy advisor to the President's Commission on Critical Infrastructure Protection. However, Badolato said, it is less easy to accomplish repairs quickly for more complex piping, control equipment, and compressors.

"Pipeline control centers, which house the SCADA systemsUwould be very difficult to replace in the short term, but pipeline operators typically maintain a redundant control center at a separate location from the main center," he said. "We need to be diligent in making sure that this practice is deployed across the board by all operators."

Badolato also said that operators need "an improved method for surveillance" for pipeline rights of way.

"To better defend the extended system, pipeline operators are seeking new surveillance techniques that may hold promise for more frequent and certain detection of unwanted activity" on the ROWs. Badolato, a retired marine colonel, said that "research and development and the commercialization of surveillance technologies developed for defense and intelligence agencies" could be a possibility for observing suspicious ROW encroachments.

"Examples of new technologies of interest," he added, involve "long-range blimps with sophisticated surveillance suites, satellite surveillance, and smart sensor cables that are programmed to detect unusual vibrations or noises."

Cost of security

Such expenditures for security technology, consultants, training, and additional personnel will become a common cost of doing business—another form of insurance—costs of which continue to rise.

Because security enhancement is outlay with little visible or tangible benefits seen, some companies may be tempted to forgo these expenses, but they then may become the unprotected, "soft targets" the terrorist groups seek.

As the US economy moves away from an emphasis on speed, or from "just in time" to "just in case," as one security pundit put it, terrorism insurance coverage has become increasingly more costly, if even available. Such coverage once was part of full coverage risk insurance, but some insurance underwriters have ceased writing new policies, and the government is being pressured to fill the void by providing an indemnification program for insurance and reinsurance companies (OGJ, Nov. 25, 2002, p. 54).

However, the US already spends about $100 billion/year on homeland security, including intelligence gathering, border protection, and the services of law enforcement personnel.

Direct federal expenditures for homeland security in 2001 was $17 billion, which increased to $29 billion in 2002 and $38 billion in 2003.

Increasingly, the federal government expects state and local governments and the private sector to shoulder other aspects of the security burden.

The National Governors' Association estimates homeland security-related costs for the states, incurred between Sept. 11, 2001, and yearend 2002, at $6 billion, and the US Conference of Mayors put costs incurred by cities during the same time at $2.6 billion. Consequently, the energy industry may be on its own for much of its increased expenditures for security. That's the bad news.

The good news is that the federal government is likely to help quickly restore damage to critical infrastructure, should it occur, including that of the energy sector, in case of a terrorist attack, because it would be in the country's best interest to keep the economic system operations uninterrupted for as short a time as possible to minimize economic disruptions.

It also is expanding nationwide efforts to prevent attacks. "To strengthen our cooperation with state and local law enforcement," Mueller said, the FBI is "introducing counterterrorism training on a national level. We will provide specialized counterterrorism training to 224 agents and training technicians from every field division in the country so that they, in turn, can train an estimated 26,800 federal, state, and local law enforcement officers this year in basic counterterrorism."

Commenting on President George W. Bush's initiative to establish a Terrorist Threat Integration Center that will merge and analyze terrorist-related information collected domestically and abroad, Mueller said: "If we are to defeat terrorists and their supporters, a wide range of organizations must work together."

The industry, as API says, must continue to maintain constant vigilance, implement resources needed for deterrence, and, "hope for the best, while being prepared for the worst."