Russian oil sector rebound under full swing

Russia's oil sector is riding the crest of a strong revival.

Russian oil production has rebounded, after falling almost 30% after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1992.

"Russia has become the world's largest oil producer and has taken a firm grip of global leadership in the export of hydrocarbon products," Russian Energy Minister Igor Yusufov said recently. Even more important, the Russian oil industry has been completely reorganized along more international lines in the course of this recovery.

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1992, a number of Russian private groups moved to seize control of state oil assets through privatizations and other means. Rudimentary oil companies were assembled ad hoc out of the fragments of the state oil system commencing in 1993. These companies began to reorganize their new assets, culminating in a flurry of activity in 1996-97.

After the 1998 fiscal crisis in Russia, the emerging Russian major oil companies began to consolidate assets more aggressively. They acquired more oil properties, streamlined operations, cut costs, introduced Western management and technology, and in most cases began listing their shares, either in Russia or abroad.

Almet Bureniya's (Tatneft) 75-tonne drilling rig works for the ZAO Tatex joint venture in Onbysk oil field 40 km northwest of Almetyevsk, Russia. Tatex is a 50-50 partnership of Texneft Inc., a subsidiary of Oklahoma City-based Devon Energy Corp., and OAO Tatneft, a Russian oil major that has operations in Russia's Tatarstan Republic. The JV dates to 1990. According to Devon, the rig drilled on the same pad four inclined wells 5-20 m apart. Average well depth is 1,200 m, targeting seven carbonate Carboniferous pay zones. The rig is moved on tractor treads from location to location in about a day. On this pad, Tatex conducted a drillbit pilot test that compared the efficiencies of Hughes Christensen insert bits vs. domestic bits. One bit, an HRS38C, drilled a record in the area for 8.5-in. hole. It made 1,444 m altogether with about 90 pure drilling hours, according to Devon. Average ROP was 14.9 m/hr. A typical Russian domestic bit makes about 200 m and averages about 13 m/hr, Devon said. Photo by Dean E. Gaddy, Devon operations manager-Russia.

Currently, Russian oil companies are seeking to increase their share prices and improve liquidity in their shares. The primary reason is that they need access to cheap capital. The surviving "oligarchs" in the controlling groups also will be able to cash out. They will leave behind a Russian oil industry organized, operated, and capitalized much like their Western brethren. Thus reformed, the Russian oil industry will be able to take up its role as a vital component of the international oil industry and more effectively exploit the tremendous oil reserves it has at its disposal.

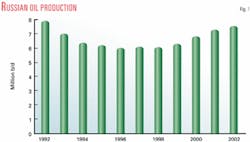

Production rebound

Oil and gas production in Russia has rebounded significantly in the last few years, after contracting sharply in the 1990s (Fig. 1). Prior to the breakup of the Soviet Union, Soviet oil production equaled that of Saudi Arabia at 11 million b/d. Such high production levels in the 1980s stemmed largely from the exploitation of tremendous new petroleum reserves discovered in Western Siberia. The Soviet state oil system produced them aggressively, in the process seemingly inflicting a fair amount of damage on the newly found reservoirs.

After the Soviet collapse, Russian oil production plummeted, falling to 8 million b/d in 1992 and to only 6 million b/d by 1996.

This reduction in oil production was the result of many factors, not least of which was the organizational anarchy in the Russian oil industry. Prior to 1992, the Russian oil industry was divided into functional enterprises of various types administered centrally under the state economic plan. Almost none of these enterprises was economically viable on a stand-alone basis. Rather, each was a relatively specialized subcomponent of a single, massive industry-wide enterprise. When the state economic planning system disappeared with the rest of the Soviet state organization, the units of the Russian oil industry were left to flounder.

From 1992 to 1998—an era in Russian business often referred to as the "robber baron" era—various groups within Russia tried to assemble these former Soviet oil enterprises into viable, integrated businesses amidst a general shortage of capital and chronic political turmoil. Various groups in the Russian oil industry competed, and ultimately succeeded, in pulling together enough fragments of the Soviet oil industry to create large, integrated oil and gas exploration, production, and refining companies. Most notable of these are the companies that now dominate the Russian oil and gas sector and compete as equals throughout the world with Western oil companies: OAO Lukoil, OAO Yukos, Tyumen Oil Co. (TNK), and OAO Gazprom, with a second tier of smaller conglomerates.

The competition at this time to assemble oil and gas conglomerates was fierce. Many abuses occurred as the competing groups fought over control of Russian oil resources. The persons controlling these groups became the billionaire Russian oligarchs now household names in Russia and famous throughout the world: Vagit Alekperov at Lukoil, Mikhail Khodorkovsky at Yukos, Michael Fridman at TNK, and Eugene Shvidler at OAO Sibneft.

This era ended with a rolling world financial crisis, which caught the new Russia economy off guard and resulted in a devaluation of the ruble, a sharp decline in foreign investment in Russia, and many Russian bank failures. The 1998 crisis in turn encouraged the surviving oil and gas conglomerates to put their houses in order if they were to weather the crisis and succeed going forward. This move to improve and normalize their operations also stem- med partly from a desire on the part of the oligarchs to diversify their new holdings, and for that reason they needed to improve share prices and enhance share liquidity. Achieving that goal in turn compelled them to make their companies more attractive to foreign buyers, either in public markets or for company acquisitions from abroad.

As a consequence, commencing about 1998, the larger conglomerates in the Russian oil industry began to systematically employ Western managers and expertise to introduce Western oil industry management practices on a significant scale. They adopted financial reporting under US generally accepted accounting principles. They began to pursue good public relations. They started consolidating their many acquisitions, reorganizing them along more businesslike lines. In many cases, these companies also issued publicly traded securities to raise capital in the West, either on the New York Stock Exchange or elsewhere, or otherwise sought foreign capital. As a result, many of the more aggressive forms of economic competition in the Russian oil industry ended.

The Russian oil industry also increasingly incorporated Western technology into its operations. PetroAlliance emerged as the premier Russian oil field service provider, incorporating Russian expertise with Western technology. PetroAlliance found a ready market for such services in Lukoil and various other Russian and foreign companies. Yukos brought in Schlumberger Ltd., and TNK brought in Halliburton Co. Currently, the Russian oil industry has state-of-the-art oil field technology readily available. The same exploration and production technology is now as available in Russia as in the North Sea or Gulf of Mexico.

The Russian oil industry in short is currently seeking to integrate itself fully into the international oil industry. Such efforts are not altruistic, of course, because the Russian oil companies fully understand that the more integrated they become in the international oil industry, the more likely they are to achieve the access to capital and stock market trading multiples of prominent international oil companies such as ExxonMobil Corp., ChevronTexaco Corp., BP PLC, and Royal Dutch/Shell Group. That economic motive provides a powerful incentive for Russian oil companies to continue on their path of managerial reform.

The more integrated the Russian oil companies are in the international oil industry, the more they will act like international oil companies. The Russian oil companies are currently subject to many of the same forces pushing the international oil industry to consolidate. Russian oil companies are beginning to respond to those pressures as well, as evidenced by the recent BP combination with TNK and the Yukos acquisition of Sibneft. In short, the Russian oil industry is not only recovering from the breakup of the Soviet Union but also well on its way to integrating with the international oil industry as a whole.

Russian oil production challenges

Russian production history

The collapse in Russan oil production resulted from a number of factors, all of which were attributable to the collapse of the former Soviet Union:

- Disorganization of the oil industry as a whole and uncertainty as to ownership of fields and product.

- Diversion of proceeds from the sale of oil and failure to reinvest oil revenues in ongoing development and maintenance of fields.

- Lack of an adequate market mechanism to ensure payment for oil produced.

- Mass shutdown of wells related to reorganization or privatization of the entities responsible for the wells.

- The after-effects of a state-mandated surge in production in the 1980s, which may have seriously depleted a number of large fields.

- Outright diversion of production.

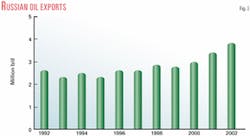

As the Russian political situation normalized and the Russian oil companies stabilized the industry, oil production stabilized too. Oil production stopped falling in 1996 and continued at about the same level through 1998. Russian oil exports similarly declined and bottomed out in 1993-96 as well, averaging just slightly more than 3 million b/d during that time (Fig. 2).

Oil production increased after 1998. The newly consolidated Russian majors could divert more capital expenditures and managerial attention to increasing oil production and reserves. By 2000, oil production in Russia had increased to almost 7 million b/d. In 2002, Russian oil production reached 7.52 million b/d, and according to Minister Yusufov, surged to 8 million b/d in fourth quarter 2002.

Russian oil exports also trended upward after 1998. Russian oil exports by 2000 had surpassed 4 million b/d. In 2002 about 3.32 million b/d was exported by pipelines and 440,000 b/d was transported by rail, and total exports approached 4 million b/d. (Some other analysts estimate that total exports in 2002 may been come closer to 5 million b/d.). TNK has projected that Russian oil exports in 2003 will increase to 3.5 million b/d by pipeline and 500,000 b/d by rail. Regardless which numbers are achieved, however, total oil exports from Russia in the short term appear to be topping out for lack of transport capacity. TNK has indicated that Russian total oil transport capacity needs to increase to at least 7 million b/d by 2012 in order to get the projected overall increase in Russian oil production to market.

Projected increases

This increase in Russian oil production will likely continue for at least the next 5 years and peak sometime during 2005-10. There is more at work in this surge in production than simply reopening shut-in wells. The current increase in production stems in part not only from enhanced development efforts of the Russian companies but also basic field recovery. Fields damaged by excessive production in the 1980s have had time to recover in the "lost dec- ade" of the 1990s.

Ongoing increases in oil production are likely to be limited by a number of factors. Reserve depletion is the primary factor. While Russia possesses enormous onshore oil fields, many of those fields have been produced for some time and are in the closing years of productive life. The Samotlor oil field in Western Siberia, for example, produced 3.4 million b/d in the 1980s but has reduced production to 400,000 b/d. Unless Russian companies add to their reserves, however, further production increases may prove harder to achieve.

There are, of course, many potential new discoveries to exploit. Deposits in the Arctic (both onshore in the Timan-Pechora region and offshore) and in the Caspian Sea are especially noteworthy. The Northern Territories reserves in the northwestern Russian Arctic are estimated at well over 4 billion bbl of oil. These fields were identified under the Soviets but never developed. Whether these and other new prospects will replace the reserves now being depleted, however, is anybody's guess.

As a result, it is hard to project how much Russian oil production will increase. Not surprisingly, there is a wide range of projections. One world oil production capacity model projects that Russian production will peak at 8.2 million b/d in 2007. On the other hand, Russian industry projections tend to be more optimistic. TNK projects that Russian oil production will increase to about 8.17 million b/d in 2003 and 8.76 million b/d in 2004. Yukos has projected that Russian production will possibly climb to back to 11 million b/d by 2010. TNK has forecast that oil production by 2012 could hit 11.5 million b/d.

While it is a hard to project the duration of the rising production trend, almost all observers agree that Russian oil production will increase, and significantly, in this decade. Whether that increase continues beyond the next 5 years depends on what reserves the new Russian oil companies can find and commercially exploit in the next few years.

What's needed now

The rebound in Russian oil production has been the work of the Russians themselves. Relatively little foreign investment in the Russian oil industry has been made, apart from the oil projects in Sakhalin. There are a number of reasons commonly cited for this relative lack of foreign investment—the absence of a favorable regulatory and tax regime for production-sharing agreements being the most notable excuse. The underlying truth is that the Russians do not need foreign oil companies to produce their oil—at least under the terms that the foreign oil companies desire.

The two particularly significant areas in which the Russian oil industry has been deficient are financial planning and technological innovation. Financially, Russians have often produced oil with little regard for its ultimate profitability and certainly have had great difficulty managing cash flow. Technically, the Russian oil industry has simply lagged behind other oil regions in creating and applying new technologies to enhance production. Both weaknesses are direct legacies of the Soviet operating regime for oil development.

The Russian oil industry, however, is overcoming these weaknesses by hiring foreign assistance in financial planning and acquiring foreign technology, either directly or by hiring service companies with the requisite foreign expertise and technology.

What the Russian oil industry really needs now is access to cheap foreign capital from the capital markets and access to world markets. The major Russian oil companies are generating significant revenues, given current oil prices, but need access to foreign capital markets to raise equity to expand their production. They are currently moving in that direction. Both Lukoil and Yukos are notable leaders in listing their bonds or shares on the London Stock Exchange and on the New York Stock Exchange (through American Depository Share programs).

Such access to additional markets is critical for the long-term profitability of the industry, because Russian domestic oil sales are in rubles at prices about half the world market price, and dumping additional oil production on the Russian domestic market would depress prices even further. A glut of Russian oil in its domestic market in 2002 has already resulted in significant price pressure—and even calls to establish a Russian strategic petroleum reserve to absorb excess production.

Access to world markets for this purpose means developing 1) long-term sales arrangements with foreign retailers of gasoline, lubricants, and other refined products to ensure that long-term investments in expanding production can be recovered and 2) the infrastructure necessary to transport increasing quantities of Russian crude to refineries abroad to serve these new markets.

The new Russian oil companies are already actively exporting their oil to foreign markets. About 6 out of every 10 bbl of oil currently produced is exported. Most Russian crude deliveries currently go to European refineries from ports on the Black Sea or Baltic Sea or via the Druzhba (Friendship) oil pipeline to Austria. These routes are reaching their capacity, with tanker traffic on the Black Sea route in particular being subject to environmental limitations at the Bosporus Straits, and the markets they serve are already absorbing a lot of Russian export oil. Western Europe in 2000 accounted for 87% of net Russian oil exports. While that amount is likely to increase, particularly given the projected fall-off in North Sea production, Western Europe cannot absorb all the additional oil Russia is likely to produce.

As an alternative, Russian oil companies have experimented with long-distance deliveries of oil to new markets, principally North America. Yukos has sent a number of tankers to the Gulf of Mexico, and Lukoil has sent a tanker to Singapore. Both appear to be trying to reduce the cost of tankering oil in order to make such shipments commercially feasible. TNK is projecting that exports of Russian oil to the US could reach 1.5 million b/d by 2008. Yukos has also actively sought to develop Eastern Siberia oil fields as a source of supply for East Asian markets.

Russian companies also have experimented with acquiring foreign chains for retail distribution of gasoline. Most notably, Lukoil acquired the Getty Petroleum Marketing Inc. retail network in the northeastern US (OGJ Online, Dec. 7, 2000). Leonid Fedun of Lukoil has said that Lukoil in the future can profitably ship up to 110,000 b/d of its Timan-Pechora oil production to North American refineries for eventual distribution as refined products through the Getty station network.

The Russian oil industry also has been actively pursuing new transportation routes for its oil. The major Russian oil companies, in the most notable recent project, announced that they would build an oil terminal at Murmansk, on the Barents Sea near the Arctic Circle (OGJ Online, Nov. 27, 2002). The terminal and related pipeline are projected to cost $4.5 billion and by yearend 2007 will increase overall export capacity by 1.6 million b/d. It also would accommodate new production from Timan-Pechora. The terminal will serve as the lifting point for loading deepwater supertankers, access to which Russian companies have previously lacked. This terminal will change the economics of Russian oil exporting to allow global deliveries to be more economically feasible.

Other oil transportation pipelines are being completed as well, such as an expansion of the Baltic pipeline system, which would increase export capacity by another 400,000 b/d by 2007. Another proposed oil transport project is the Adria pipeline in Croatia, which will give Russian oil exporters access to the Adriatic Sea at the port of Omisalj. Other pipelines are on the drawing board, most notably a Yukos proposal for a 2,400 km pipeline from Angarsk in Eastern Siberia to Daqing in China and a OAO Transneft pipeline from Angarsk to a Russian Far East export terminal at Nakhodka.

Major players

Lukoil

Lukoil is the preeminent Russian oil company, with much of its production in the prolific Western Siberian oil fields. It ranks among the world's top five publicly traded oil companies by reserves, exceeded only by Exxon- Mobil, Shell, and China's state-owned PetroChina. Lukoil was formed in 1993 in a Russian governmental reorganization of the state owned oil company Langepas Urai Kogalymneft. A number of Russian oilmen led by Alekperov emerged as the controlling management group of Lukoil. That group has remained in control to this day and has led Lukoil's growth to a world-class oil company.

In a series of reorganizations occurring during 1993-97, Lukoil integrated a number of other Russian oil enterprises in itself, including the oil production associations Permneft, Nizhnevolzhskneft, Kaliningradmorneftegas, and Astrakhanneft. In 1999 it began acquiring additional companies, including those in Russia's Komi and Saratov regions as well Ukraine and Bulgaria.

Lukoil's current oil production is 1.5 million b/d, about 2% of the world total. Lukoil's oil production has not increased as rapidly as Yukos's has in the last 2 years, growing in 2001 by about 9%, which has been a point of some criticism of Lukoil. The firm, however, has focused upon increasing and developing overall oil reserves rather than increasing daily production, i.e., by investing in new fields for future production.

Lukoil's proven oil reserves total 14.576.5 billion bbl, and proven natural gas reserves over 13.216 tcf. Probable oil reserves are 6.657 billion bbl, and probable natural gas reserves are 3.524 tcf. Oil reserves are concentrated in Western Siberia, with significant fields in the Tyumen, Timan-Pechora, and Ural-Volga regions, with PSA interests in fields in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, and a number of joint ventures in a variety of regions including, LukArco, its joint venture with ARCO (now part of BP) on the Caspian Sea shelf. Western Siberia, however, still accounts for 57% of Lukoil's domestic proven reserves.

Lukoil transports its oil several ways. Most oil from European Russia and Western Siberia is transported in the Transneft system; however, Lukoil is also actively seeking alternatives for oil transport. It has begun exporting oil from Timan-Pechora to a temporary terminal at Varandei Bay on the Arctic Sea and has acquired a fleet of tankers and icebreakers for that purpose. Lukoil has also invested in the Caspian Pipe- line Consortium and publicly supported the Murmansk oil terminal proposal.

The company also owns four major refineries in Russia—in Perm, Volgo- grad, Ukhta, and Nizhni Novgorod—with combined capacity of about 760,000 b/d. It also has refineries in Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Romania.

Lukoil has an extensive retail distribution network in place and growing. It operates 1,384 Lukoil branded retail outlets in Russia, 883 in other countries of the FSU and Eastern Europe, and 1,279 leased retail outlets in the Getty USA network, mostly in New York and New Jersey.

Lukoil's business strategy advances its prospects in international capital markets. While there are other reasons for focusing on developing a strong reserves base vs. building production, the international capital markets generally value reserves more highly than current production. Lukoil is presumably seeking to support its stock price in Russia and position itself to list more shares in the West. It has already listed some shares under the ADS program.

As a result of its growth in reserves, Lukoil is positioned to benefit in the future as Russian oil companies obtain better stock market multiples on a par with Western oil companies.

Yukos

Yukos produces over 1.5 million b/d, second only to Lukoil as a Russian oil producer. With its acquisition of Sibneft, Yukos will surpass Lukoil.

Yukos was formed by the Russian state in 1993 from the combination of Yuganskneftgas and Kuibyshevnefteorgsintez. After a rather rough start, the Russian government in 1995-96 privatized Yukos in a number of tenders. Commencing in 1996, managerial control of Yukos passed to Khodorkovsky and a group affiliated with Menatep Bank. Khodorkovsky has maintained control to this day, streamlining operations, cutting costs, and investing in drilling, capital construction, and new oil fields. In 1997, Yukos began acquiring companies, including Tomskneft, and has continued an active program of acquisitions up to the recently completed Sibneft acquisition.

Yukos's current oil production has almost equaled that of Lukoil's as a result of the former's focus on existing field development and acquisitions. While Yukos has emphasized building current production more than reserves growth, it has nevertheless managed to increase both. The company estimates that its production, exclusive of Sibneft and other acquisitions, will jump to 1.66 million b/d in 2003 from 1.39 million b/d in 2002.

Meanwhile, Yukos' oil reserves in 2001 totaled 13.3 billion bbl. This number does not include significant additional acquisitions of companies such as Arcticgas (Rospan) and Urengoil, or expanded field development. Oil reserves are concentrated in Western Siberia, particularly the northern portion of Priobskoye oil field in Khanty Mansiysk, and in the Samara, Eastern Siberia, and Tomsk regions. It also holds notable PSA and joint venture interests in the North Caspian (with Lukoil), in the Black Sea (with Total SA), and in Kazakhstan.

Yukos sold 51% of its oil abroad in 2002. It transported about half its crude oil in 2002 to Europe by Transneft's system, with the balance going to other FSU countries and China. Yukos also is actively seeking other transportation routes, having actively supported the Murmansk oil terminal proposal and the Omisalji pipeline and serving as the lead proponent of the Angarsk-Daqing pipeline. Yukos also has been actively exporting oil to new markets by tanker, shipments to the US commencing in July 2002 being the most notable example.

Yukos, like Lukoil, has an extensive refining network. Yukos has interests in six main refineries: three in Samara, one in Western Siberia, one in Eastern Siberia, and a controlling interest in the Mazeikiu Nafta refinery in Lithuania.

Total capacity of these refineries in 2002 was 658,000 b/d. Yukos also distributes refined products through a network of over 1,200 branded retail outlets in Russia.

TNK

TNK was formed in 1995 in a Russian governmental consolidation of eight Russian oil production enterprises. In 1997-98, a coalition of Russian investors headed by Fridman acquired control of TNK in a number of privatization auctions. Having obtained working control of TNK in 1998, the Fridman group commenced an effort to consolidate TNK's operations and create a vertically integrated oil company. They also began acquiring additional companies, such as Chernogorneft, and a controlling stake in Sidanco.

TNK currently is one of the top 15 private vertically integrated oil companies in the world. It grew from 393,000 b/d of oil production and 4 billion bbl in proven reserves in 1998 to 800,000 b/d and 8.2 billion bbl in 2000. Since then, production and reserves have continued to increase dramatically. In February, BP announced that it would invest $6.7 billion in order to acquire 50% of TNK. This transaction also will result in the merger of Sidanco (owned 57% by TNK and 25% by BP) into TNK.

Current industry consolidation.

BP's recently announced combination with TNK is one of the more notable consolidations under way in the Russian oil industry.

BP has had a long history of dealing with TNK. In 1997, BP acquired 10% of Sidanco. Most of Sidanco's assets subsequently were acquired by TNK in Sidanco's bankruptcy. BP and TNK fought a long battle in the Russian courts for control of Sidanco. The rulings of the Russian courts involved ultimately vindicated TNK's position. BP and TNK subsequently resolved their feud, and BP acquired a 24% plus one share "blocking" interest in Sidanco, with the majority of Sidanco shares held by TNK.

With the latest transaction, BP and the Fridman group each will own 50% of TNK and certain additional assets to be merged into TNK, including Onako, another, smaller Russian oil company. This investment is widely regarded as the most significant foreign investment in the Russian oil industry since perestroika. In fact, it will amount to one third of the foreign capital invested in Russian since 1992.

Given that BP has turned from an active adversary of TNK to its advocate, this transaction is a major vote of confidence in TNK and its prospects. Even more, the sheer scale of the BP investment constitutes an acknowledgement that the Russian oil market is ready for foreign investment directly in Russian oil companies. Finally, the fact that the Russian government is permitting the combination to proceed signals that the government is ready to yield managerial control over Russian production to pass into multinational hands. That governmental reaction, even more than BP's investment itself, is the most convincing sign that the Russian oil market has matured for integration into the world oil market.

The merger of Yukos and Sibneft is another noteworthy current acquisition in the Russian oil sector. The combined new entity will have 18-19 billion bbl of oil reserves and 2.2 million b/d of production. Shares in the new YukosSibneft company will be almost a third of the Russian stock market, a $36 billion company. YukosSibneft will rank sixth in the world for oil production, behind Total.

The YukosSibneft transaction is instructive on several levels. First, it creates a company so large that a foreign acquisition would be difficult. Indeed, its genesis may have been as a defensive move by Yukos, since a number of foreign companies had been rumored to be in talks with Sibneft. The sheer size of YukosSibneft almost ensures that it will have a place in the portfolios of energy fund managers. Both Yukos and Sibneft had followed strategies to promote share prices in international capital markets and rapid production growth—Yukos's production increasing 20% last year, and Sibneft's 28%.

The TNK and Sibneft acquisitions, accordingly, are unlike Western mergers of oil companies. Most major Western mergers in the oil industry are intended to realize economics of scale, at least at some level, regardless what other reasons may be proffered. The TNK and Sibneft acquisitions are instead focused on increasing share price and liquidity for Russian shareholders–especially the oligarchs. Whether the oligarchs are trying to get out at the top of the market, paving the way to pursue political careers, or cashing out simply to diversify their holdings, it is clear that realizing better share prices and liquidity controls their current overall business strategy.

Others

A second tier of oil producers has also emerged in Russia. These middle tier Russian oil companies are the most likely targets for investment in the Russian oil industry. Sibneft has obviously just fallen to Yukos, but companies such as OAO Rosneft, Surgutneftegaz, OAO Slavneft, OAO Tatneft, and OAO Bashneft have so far remained largely independent. A number of smaller entities also offer potential footholds for foreign investment in Russia.

Marathon Oil Corp., for example, recently agreed to acquire Khanty Mansiysk Oil Corp., which produces about 15,000 b/d of oil, for $275 million.

Since Russian oil reserves held in such companies are typically valued at 25% or less of the average global valuation, such companies are attractive potential targets for foreign companies. However, there are a limited and rapidly diminishing number of such companies. Many are already being courted by Western suitors or being targeted by the Russian majors.

Foreign investment

Direct asset acquisition

Non-Russian oil companies in the future are not likely to be able to acquire major oil fields in Russia directly. Historically, some oil fields have been granted for development to joint ventures with foreign companies with varying levels of success, but the major projects for the most part never quite got off the ground. Projects such as the former Amoco Corp.'s development project in Priobskoye oil field or the former Texaco Inc.'s project in Timan-Pechora never progressed to fruition despite tens of millions of dollars of advance expenditures and years of effort. The only major projects so far to show success are those to explore for and develop fields in the Sea of Okhotsk off Sakhalin Island, where a consortium headed by Shell is producing 80,000 b/d of oil. But even Shell in November 2002 threatened not to commence the next phase of its Sakhalin project (costing $8.5 billion) unless modifications to Russia tax laws are made to provide for certain production sharing tax preferences.

There is a number of reasons for the general failure of foreign oil companies to develop major concessions in Russia. Chief of these factors has been the lack of a production sharing regulatory and tax regime to the foreign oil companies' liking. The foreign oil companies almost universally have sought to take oil fields under PSAs.

The mechanism for using PSAs in Russia has never been fully put in place. Although the Russian Duma has adopted a production sharing law, the regulatory modifications required to implement its provisions have not been adopted. Modifications to the Russian tax code to provide for tax exemptions or reductions are the primary ingredient missing.

Despite active lobbying by foreign companies, such legislative actions are not likely to be taken anytime in the near future, if ever. Russian oil companies have actively opposed such modifications and lobbied against them, either openly or covertly. Yukos has been the most open opponent to such modifications. Khodorkovsky has opined that production sharing laws will create "preferences and provoke corruption." The Russian companies argue that it is contrary to free market capitalism to provide tax and other preferences to foreign companies competing with Russian companies developing Russian oil resources.

Opponents to such a PSA regime in Russia have a point. The Russian oil industry has a long history of finding and producing oil. It found and developed world-class reserves under the Soviet Union and, despite the breakup of the Soviet Union, continued to produce oil without significant state support or funds. The Russia oil industry currently retains hundreds of thousands of experienced geophysicists, geologists, technicians, and managers. The Russians, in short, do not need to attract foreign investment by offering preferential production sharing terms to develop their resources.

Opportunities

While production sharing may not be available generally, there are three areas in which the Russian oil industry needs help from abroad and for which preferential terms may be available.

First, the Russian oil industry does not have much experience in offshore oil development, especially with deepwater prospects. Second, the Russian oil industry has extensive experience operating in arctic conditions but does not have the latest techniques or extraordinary financial resources required for such operations. Third, oil field development either offshore or in arctic conditions requires investment of massive amounts of capital for long periods, which would stress the balance sheets of even the new Russian majors.

As a result, there may be opportunities in the future for foreign oil companies to obtain preferential terms to work on capital-intensive projects in offshore or arctic oil fields. It is instructive that the one major project permitted by the Russian government to continue on production sharing terms is the Sakhalin project, a large-scale offshore development in arctic conditions.

Direct investment

Foreign oil companies do have opportunities to invest in Russian oil fields apart from production sharing terms.

First, majors can invest directly in Russian oil companies, as BP has invested in TNK recently. Second, foreign oil companies can enter into strategic alliances with Russian oil companies. The LukArco strategic joint venture to develop the North Caspian is one example. Third, farm-out or informal sharing arrangements are possible, although seldom attempted onshore in Russia. Such arrangements, however, might prove more workable in offshore fields where production can be taken off platforms directly to tankers so that there are fewer local issues to complicate matters, although the tax regime obviously still matters.

The underlying weakness of all these approaches is that they require the foreign oil companies to work with Russian companies as equals. Major Russian companies will not turn over onshore operations in Russia for foreign companies and are loath to surrender control even over offshore prospects. Unfortunately, most larger Western oil companies prefer to operate projects on their own, subject to farmout to other players. Given the way Russians conduct business, however, it might prove better for foreign companies to experiment with some smaller projects in order to earn the Russian companies' trust for larger projects.

Effect on OPEC

Russian production growth is likely to destabilize the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Reintroduction of Russia as a predominant oil exporter worldwide would seriously undermine OPEC's influence over world oil prices. OPEC's oil quotas are essentially enforced by Saudi Arabia, which is the only OPEC participant with sufficient oil reserves to flood the market with enough oil on 90 days notice to depress oil prices significantly. This potential sanction is what keeps the other members of OPEC in line.

If large additional volumes of Russian crude were to come on the world market, then that production would not only tend to drive down prices generally but also drive them to levels where Saudi sanctions might not be as effective. Additional Russian production would also impair OPEC's ability to raise oil prices through production cuts by increasing the overall float of crude oil available in the oil markets to pick up any demand resulting from OPEC production cuts. With less ability to raise prices and without the discipline supplied by the Saudis, OPEC might well weaken as its members seek to outproduce one another in order to keep up their oil revenue streams and thus finance their respective domestic agendas.

The Russian government is at least as interested in undermining OPEC's pricing power as is the US, perhaps more so. While the US can restrain the Saudis somewhat because of the former's global political position, the Russian government has little such influence. In addition, the Russian oil industry has openly chafed at various attempts by OPEC in late 2001 and early 2002 to pressure the Russian government to rein in its own oil production—which were for the most part rebuffed. While the Russian oil producers certainly appreciate higher prices, they will benefit little from higher prices if they cannot produce oil to sell at those prices. F

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Erik Norris of Haynes & Boone LLP for his assistance in preparing the information on Russian gas production utilized in this article.

Bibliography

Bakhtiari, A.M. Samsam, "Expectations of Sustained Russian Oil Production Boom Unjustified," OGJ, Apr. 29, 2002, p. 24).

Mason, R., "Some Perspective on the Yukos Sibneft Merger," Oil & Gas Advisory, Apr. 30, 2003.

Stinemetz, D., "New Friends in the New World Order: The Russian-American Energy Alliance," Oil & Gas Insight, January 2003.

Tavernise, S. and Brauer, B., "Russia Becoming an Oil Ally," New York Times, Oct. 19, 2001.

Tavernise, S. and Banerjee, N., "Why US Oil Companies and Russian Resources Don't Mix," New York Times, Nov. 24, 2002.

Author's note

This article includes information derived from many sources. The information comes from personal communications as well as review of academic publications, statistical data, and similar sources. There is no single authoritative source for Russian oil production and exports during 1992-2002. Various sources use different methodologies to compile their data. Such data during 1992-2002 are inherently suspect because a number of factors affect them, such as 1) significant amounts of Russian oil production and exports in that period were delivered out of normal channels, 2) oil production from other countries being routed through Russian pipelines may have been counted as Russian source production, and 3) record-keeping on Russian oil production and exports simply did not keep up with the constant reorganization in the Russian oil industry at the time. As a result, data on Russian production and exports presented in this article have been compiled from many sources. For example, a number of sources state that overall Russian oil exports in 2001-02 almost reached 5 million b/d. The latest information the author has received on such exports from Russian industry sources, however, indicates that actual exports in that period only approached 4 million b/d. Regardless of the amount, however, the numbers show that Russian exports were topping out in 2001-02, presumably because transportation capacity limits had been reached. Such data as a result should not be considered precise but rather indicative of overall trends in Russian oil production and exports.

The author

Doug Stinemetz has represented companies pursuing oil prospects in the former Soviet Union since 1988. He is a partner at the law firm of Haynes & Boone LLP in Houston and focuses on structuring and completing oil and oil field service projects in Russia, Central Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Stinemetz speaks Russian. He obtained a BA from Harvard College in 1980, an MA from Harvard Graduate School in 1983, and a JD from New York University School of Law in 1986.