Higher natural gas prices will decrease profitability of US petchem industry

Higher normal natural gas prices in 2004-06 could lower the peak cyclical profits of US chemical producers of methanol, ammonia, ethylene and its derivatives.

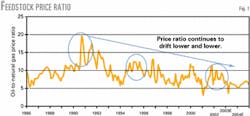

For the 15 years through 1999, US consumers of natural gas enjoyed a "golden era" of cheap and plentiful feedstock. The ratio of oil to natural gas prices was at or above 10, making US natural gas-based chemical plants competitive vs. Western European and Asian oil-based chemicals.

The US is the world's leading supplier of chemicals, with gross exports of 13-15% and net exports of 5-7% of total US production.

Since 1999, however, the absolute natural gas price doubled and the oil:natural gas price ratio declined to 6-7 (Fig. 1). Because oil prices, the US economy, and the global economy also experienced increased volatility in 1999-2002, conventional wisdom suggests delaying any conclusions until the world economies resume a normal pace.

Recent US natural gas prices are on a higher secular level, beyond seasonal and cyclical blips. We are adjusting our "normal" expectations, therefore, for some natural gas consumers—specifically for petrochemical products and companies.

Rapid fluctuations in energy costs are typically bad for commodity and specialty chemical companies; the pace of chemical price increases always lags the pace of energy price changes. Profit margins, therefore, are squeezed during energy cost spikes and often are not fully recovered later.1

Diverging supply-demand trends

Supply and demand trends are diverging; the resulting gap would take an even higher US natural gas price to bridge it using interfuel substitution. The supply and demand of US natural gas entered new, uncharted territory since 2000 when average annual prices increased by 50% or more. These data points represent a new trend rather than statistical noise.2

Supply. Plummeting productivity of current US supply will not be offset by an increase in LNG imports due to the long-term lag factor related to obtaining environmental permits and construction of those terminals. Supply of Canadian gas via pipeline seems to have stabilized recently. If these assumptions are accurate in the near term, the US natural gas supply will be flat or decrease during the next few years.

Demand. Natural gas demand will increase if the US industrial economy improves as expected. Natural gas consumption increases 1.1% for every 1% rise in industrial production, based on historical US Department of Energy sensitivity analyses. If US industrial production returns to the 2.5-3.0%/year growth of the 1990s, traditional demand for natural gas will increase. The US electric utility industry will also add capacity, 91% of which is based on US natural gas.

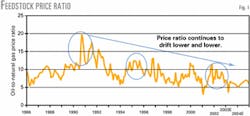

Natural gas consumers are diverse in terms of natural gas use/unit of output, demand-price sensitivity (residential vs. commercial vs. utilities), export pressure (in their markets), and competition from oil-based products and processes.

The key determinant of future US natural gas prices is the price that customers can bear, rather than the price that producers need to earn a return. This is true for energy-intensive and price-sensitive gas users such as petrochemical, fertilizer, metals, paper, paperboard, and power producers.

Fig. 2 shows that the utility and residential sectors (two relatively gas price-insensitive end markets) account for about 25% and 22% of total US gas consumption, respectively.

In the 1990s, inexpensive natural gas and Clean Air Act requirements caused the US electric utility industry to focus on natural gas as the main energy source for new production capacity. Even with some project cancellations, natural gas accounts for 90% of all new US power generation capacity planned for this decade.

Historically, electric utilities have passed fluctuating energy costs along to regulators and through contractual provisions with customers. Despite a recent increase in market share by non-regulated utilities, the entire industry is still less natural gas price sensitive than many other industrial consumers.

Price-insensitive customers could hurt chemical producers by bidding up natural gas prices, especially when US industrial production starts a long-awaited recovery in late 2003-04.

Higher prices

Price-demand elasticity self regulates imbalances in the short term; in the longer term, higher prices could stimulate more production, particularly if the government relaxes environmental restrictions on offshore drilling.

Long-term natural gas prices should raise the oil:natural gas price ratio to about 5-6, or roughly $4.50/MMbtu.

Residual fuel oil, a low-value product, has historically determined the ceiling price for natural gas at about a 7.5 oil:natural gas price ratio. When gas prices would rise to that level, some customers with switching flexibility would reduce natural gas use, which slows the rise in natural gas prices.

Now the new ceiling for natural gas prices is about a 5.0-5.5 oil:natural gas ratio, which provides an incentive for some consumers to switch from natural gas to distillate for heating. Those producers that have switching ability and exact amounts are not clear because the industry has not been tested by higher gas price market conditions.

We recently raised our 2003 gas price forecast to $5/MMbtu to reflect the price strength exhibited early in the year and stronger-than-expected natural gas storage withdrawal rates, even after adjusting for weather. We also increased our 2003 oil price forecast to $27.50/ bbl.

We expect oil:gas price ratios of 5.5 for 2003 and 5.0 for 2004. Natural gas would suffer intense competition from distillate oil products if prices exceeded this ratio. Past oil:gas ratios were lower than our estimated 5.0 for 2004 only in first quarter 2001, when gas demand dropped sharply.

Price-sensitive consumers will experience a second "gas price shock season" if high prices last into spring. Demand may fall because operators may switch to alternative fuels or decide to shut down production.

Impact on US chemicals

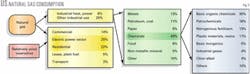

Ammonia, methanol and ethane-based ethylene are the chemicals most sensitive to high natural gas prices (Fig. 3). This is due to high consumption and lack of economically viable switching options, unless this flexibility already exists, as with flexible ethylene crackers.

Retrofitting existing capacity with oil-natural gas switching flexibility is prohibitively expensive. For many older units, the most economically viable solution to unfavorably high natural gas prices is to simply shut down.

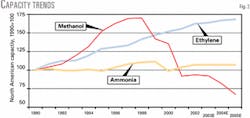

In fact, about 45% of US methanol production has shut down since 1998, in contrast to about 6% of shutdowns for US ammonia and ethylene production.

US ethylene production

Compared to naphtha-based crackers, natural-gas-based plants are less expensive to build and operate.

Because the US has had low-priced and plentiful natural gas for many years, it became the feedstock of choice for almost all ethylene crackers built in the 1980s and 1990s. The North American chemical industry has therefore become much more dependent on natural gas than other regional competitors.

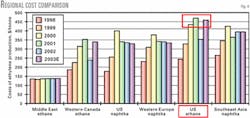

About 60% of US ethylene production uses ethane and propane for feedstocks vs. less than 15% in Asia and Europe. The Middle East is the only other region as dependent on natural gas, but that gas has a much lower price ($1.00-1.50/MMbtu). The oil:natural gas price ratio is therefore important for US ethylene-based chemicals for competitive cost-of-production reasons.

Fig. 4 shows that US ethane-based ethylene producers have the highest estimated costs in 2000, 2001, and 2003. This fact will have profound implications for US trade patterns in ethylene derivatives.

Impact on US trade

The trade balance will also be affected by high natural gas prices. Peak ethylene, polyethylene, or ethylene glycol profits depend on the ability of producers to pass along higher prices, which are determined in the short-term by the market structure and in the longer-term by price-demand elasticity.

In contrast, the US ethylene trade balance will feel more of an impact from the change in oil:natural gas price ratio as it shifts the relative competitive advantage of US producers to Western European and Asian naphtha-based peers.

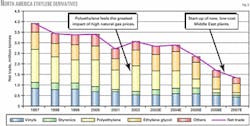

Since 2000, the US net trade balance in main ethylene derivatives declined; this trend will continue if high natural gas prices persist.3

In 2007 and beyond, we expect acceleration of this trend when new cost-competitive, ethane-based ethylene plants start up in the Middle East, with West Europe and Asia as export markets. Three large-scale, naphtha-based ethylene crackers are scheduled to start-up in China in 2006.

We expect those crackers to have instant preferential access to the domestic Chinese market with the help of Chinese state and local governments, which have a 50% stake in those joint ventures. Meanwhile, this shift will displace some US and Korean ethylene derivative imports.

In addition to ethylene and propylene, high natural gas prices will also affect other derivatives such as polyethylene, ethylene glycol, vinyl acetate monomer, and oxo-chemicals (Fig. 5); less so for styrenics, polypropylene, and vinyl chloride monomer. Chlor-alkali and titanium dioxide are relatively insulated from natural gas prices.

We cut our expected cycle-peak cash profits for petrochemicals by 10-15% due to 25% higher costs, partially offset by peak pricing. We cut cash profits for intermediates by 10% due to less cost push, but also less of pricing power.

References

1. Vasnetsov, S., "Energy Costs vs. Chemical Profits: The fight you can't avoid, but can't win," Chemical Management Review, July/August 2000, Vol. 2, No. 4.

2. Driscoll, T., Vasnetsov, S., and Patel, D., "The 'NEW ERA' of Structural tightness in US natural gas market," Oil & Gas Investor, April 2003.

3. Vasnetsov, S., and Kovenya, Z., "Cyclical and Secular Trends in US Chemical Trade," Chemical Management Review, Feb. 17, 2003, Vol. 263, No. 7.

The authors

Sergey Vasnetsov is a senior research analyst at Lehman Brothers Inc., New York City, with responsibility for covering the major US chemical companies. His experience includes 11 years of chemical research experience, both in academic and applied industrial areas. For the past 7 years, his research has focused on key fundamental drivers that shape the global chemical industry. Vasnetsov holds an MSc in chemistry from Novosibirsk University, Russia, and an MBA in finance from Rutgers University, Newark, NJ.

Zoya Kovenya is a graduate student at New York University, studying economics. She holds an MSc in economics from Moscow High School of Economics and a BSc in mathematics from Novosibirsk University, Russia.