In any meaningful discussion of the Iraqi oil industry and future policy options, three issues need to be addressed.

First, Iraq has huge oil potential that still needs to be developed.

Second, the domestic politics, wars, and economic setbacks of the past few decades have left their imprint on the oil industry with the inescapable conclusion that one has to deal first with the ramifications of these issues before embarking on the development of a new and revitalized oil sector.

Third, a future Iraqi oil policy will necessarily reflect the political and economic conditions of the country in the next few years as well as political stability in the Middle East as a whole.

Oil potential

Iraq is one of the least explored among the rich oil countries, yet it possesses some of the richest hydrocarbon basins, second only to Saudi Arabia.

In fact, around 526 structures have been discovered, delineated, mapped, recorded, and classified as potential prospects, but only 125 have been drilled, representing about 20% of the total prospects discovered so far.

Accordingly, large parts of the country remain untapped and wait to be explored and developed

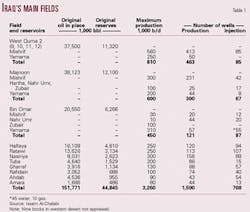

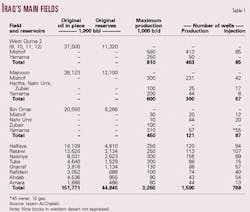

Specifically, today only 17 fields are developed out of 80 discovered (Table 1).

The rest include:

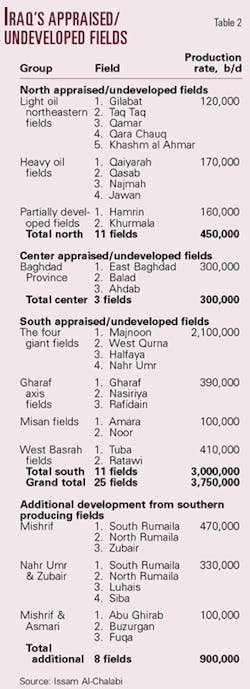

- Eleven new fields in the south with a production capacity of 3 million b/d;

- Eleven fields in the north with a production potential of around 500,000 b/d;

- Three other fields in central Iraq with a capacity of 300,000 b/d;

- And, the possibility to produce 900,000 b/d from partially developed reservoirs in existing producing fields.

In other words, Iraq has the potential to produced 4.7 million b/d more oil from discovered fields that are ready to be developed (Table 2).

The pre-August 1990 data, using exploration, drilling, and reservoir studies available at the time, estimate Iraqi proven oil reserves at 112 billion bbl with oil in place put at around 250 billion bbl. However, almost no serious work on updating those figures has been carried out since then. In fact, these figures are preliminary in nature since work was often interrupted by political problems, and the technology used is now outdated.

Although oil was discovered in 1927, potentials were not explored to their fullest limits, compared with countries in the gulf, until many years later. Up to 1961, proven reserves were estimated at 34 billion bbl.

There was little exploration by international oil companies (IOCs) and Iraq National Oil Co. (INOC) in the 1960s.

During the 1980s, due to the Iraq-Iran war, there was limited activity; and there has been almost none since 1990. Moreover, there has been no horizontal or deep drilling, and only very limited amounts of directional drilling in selected fields.

Water injection has been the only means of maintaining pressure, while gas injection was experimented on in one field only. Furthermore:

- Many discovered pay zones in currently producing fields are yet to be developed.

- Appraisal and production have been limited to some pay zones of the reservoirs.

- None of the deeper pay zones have been put into production.

- The western desert and the Northwestern part of the country remain unexplored with promising geological reserves.

Exploration-development

During 1968-90, Iraq depended on its national efforts to develop its oil potential, with the exception of three service contracts signed with France's Elf (Buzurgan field), Brazil's Petrobras (Majnoon field), and India's ONGC (a block in the western desert).

These contracts were terminated amicably in the late 1970s. Cooperation with international firms was limited after that to engineering, construction, and service firms (Table 3).

In early 1990, Iraq decided to speed up development activity through the efforts of IOCs and INOC. Talks were initiated with international firms in February to engage in buyback contracts to raise production capacity to 6 million b/d. This effort was disrupted with the invasion of Kuwait in August.

Soon after the second gulf war, in mid-1991, Iraq invited France's Elf Aquitaine and Total to unilaterally negotiate production-sharing agreements (PSAs) for giant Majnoon and Bin Omar fields, with a total production capacity of over 1 million b/d.

This effort, which resulted in the signature of MOUs but never full agreements, was part of the government's campaign to re-establish contacts with the outside world after the severe isolation following the invasion of Kuwait.

This was followed by a major oil conference in Baghdad in March 1995, culminating in first-half 1997 with the signature of development and production contracts (DPCs) with a Russian consortium led by Lukoil for the second stage of West Qurna field (600,000 b/d) and China National Petroleum Co. for Ahdab field.

The Lukoil contract was canceled in December 2002, but in January 2003 Iraq agreed to hold talks to discuss the dispute.

Meanwhile, in early 2000, the DPC contracts were modified to reflect more the buyback-type accords. Moreover, Iraq signed several MOUs for smaller fields with a number of companies from friendly countries, including Algeria, Tunisia, Viet Nam, and Syria.

Iraq also signed some deals in January 2003 with Russian companies for blocks 4 and 9. Development of 100,000 b/d Rafidain oil field was assigned to Russia's Soyuzneftegaz, and an agreement was initialed with a Russian firm for the development of the Bin Omar field (Table 4).

But it should be noted that no works were carried out on the ground for any of the above deals, including those involving Lukoil and CNPC, except possibly for some data collection and basic design.

The legality of those deals could well be questioned by a new regime. While some consider them binding since they were signed by a recognized government, others believe that the motive for them was purely political and that they were in violation of UN sanctions. I believe that for many reasons, all those deals will be re-examined on a case-by-case basis.

Finding grounds for invalidity may prove not to be such a difficult task. Rather than seeking arbitration in international courts, it might be more advisable for the companies to seek settlement through direct negotiations backed by their own governments.

The economic interests of Iraq, and technical and financial capabilities—as well as political considerations—will determine the fate of those deals. This process could well take some time, thus hindering the possible progress of new ventures in terms of allocating fields and blocks.

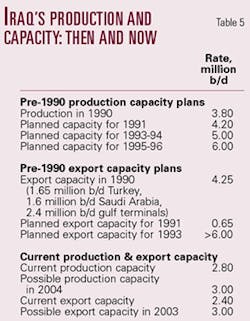

Production, export capacity

As was stated earlier, Iraq's plans in early 1990 were to raise production and export capacity to around 6 million b/d by 1996 through the joint efforts of INOC and the IOCs. This target is still attainable, at around 2010, in a post-Saddam era, and after a period of stability (Fig. 1)..

Click here to view Iraq Oil Fields

This program will entail:

- Drilling of 2,000 wells during 10 years.

- Installation of new oil and gas facilities for 25 appraised fields.

- The expansion of current capacities of eight fields.

- The reconstruction of surface facilities of three other fields over a period of 5-10 years.

It is highly recommended that current producing fields, with a capacity around 3.5 million b/d, continue to be developed by the national oil company, with technical and service assistance from international firms.

Contracts for already-discovered and undeveloped fields can be signed with IOCs and NOCs on PSA, modified buyback, or DPC terms. The modified buyback arrangements would be for a defined during, a specified percentage for local participation, and a specific commitment for the contractor to achieve a target production within a set period of time, including a multiphase development scheme.

The nine blocks in the western desert and the area of the northwest would be awarded on a risk contract basis.

As mentioned above, contracts already signed would be reviewed to determine their economic interest for the country.

According to official Iraqi data, the highest percentage of proven reserves to be produced will be of the heavy type (26° gravity and less), constituting 48% of the total; the medium-regular type (27-37° gravity) will make up 43%; and the remaining 7% will be extra-light crude (38° gravity and up).

Another factor to bear in mind is the benefit of the low cost involved in finding, developing, and operating Iraqi fields.

The oil could well be the cheapest in the world, which will prove an attraction for IOCs compared to other ventures in neighboring countries.

In my view, talk of raising production and export capacity to 8 million b/d is premature; and such a move would be very expensive in terms of capital costs and operational needs. Iraq can, at some point, consider a production target of around 8 million b/d, but only after reaching the earlier target of 6 million b/d, after 2010 at the earliest (Table 5).

Future oil policy options

Principles

Certain facts permeate the Iraqi oil industry upon which there is close to unanimity among its oil professionals:

- Natural resources should remain under state sovereignty.

- The oil industry should remain centralized whether Iraq remains a unitary state or a federal one.

How the oil revenue will be distributed is another matter. It is expected that more funds would be allocated to the provinces after much deprivation under the present regime.

- The first task for the oil authorities would be to get production capacity, damaged by wars, sanctions, and poor operating practices, back into a proper shape.

This will require much effort, funds, and technical assistance. Parallel efforts will be needed to upgrade production capacity and ensure the export facilities for them, including the re-opening of the Iraq-Saudi pipeline system and the rehabilitation of the country's gulf export facilities.

The possibility of a decline in Iraqi production at the early stages should not be dismissed. Service, engineering, drilling, and construction companies will be among the first needed to provide assistance far earlier than the IOCs.

- There will be a need during the first few years to allocate large sums to rehabilitate and modernize the oil sector.

It is estimated that it will take a minimum of two years of hard and unrestricted efforts, plus around $3 billion, to bring Iraq's oil production capacity to its pre-August 1990 level of 3.5 million b/d.

- Much effort will be needed to undertake basic modernization and rehabilitation of the present midstream and downstream sectors.

Very little investment has been put into these two sectors in the past two decades. While new equipment was bought under the UN Oil-for-Food program, hardly any new technology systems have been introduced.

Investment will be necessary to upgrade the refineries, gas processing, and petrochemical plants to meet new environmental and commercial standards. Related infrastructure including power generation, distribution, communication, ports, etc., need to be maintained and upgraded.

- There should be a level playing field for the IOCs to participate in the oil industry, either individually or on a consortium basis.

There will be much demand for technology and investment—way beyond what can be marshaled domestically either by the public or private sectors, especially since there will be much need for funds to finance basic infrastructure and social services.

- It is expected that there will be external (foreign governments and investment firms) and domestic (local authorities and political groups) pressures to influence the oil decisionmaking process.

Hence, it is important to adopt right from the start a transparent system, establish professionally accepted practices, and allow for a rational and efficient decisionmaking process by the Iraqi oil professionals.

- It is assumed that the overwhelming number of personnel currently running the oil industry will continue doing so.

Changes would affect the top decisionmakers only.

- Activities in the oil industry should not be limited to the upstream sector.

It should also be directed towards the downstream, gas, petrochemical sectors and other related infrastructures; electricity, water, ports, housing, and others.

- There will be an immediate need for training of personnel.

Many highly skilled personnel have left the country, causing one generation gap or even two. Access to modern technologies has been denied or restricted.

- Iraq, with its huge oil reserves, has a vested interest in prolonging the lifespan of oil use in the world economy as long as possible and maintaining the hydrocarbon share in the energy mix.

This means Iraq's national interest lies in maintaining its membership in OPEC and ensuring stable oil markets, the security of supply, and prices that are conducive for both producers and consumers. Iraq's interest does not lie in unstable markets or steep-cheap prices.

The subject of quota allocation and adherence to the OPEC system should be addressed with caution and understanding from within the organization and not from outside. Since Iraq will need time before being able to increase its capacities, this issue need not cause problems.

- Necessary steps

In addition to these principles, certain steps need to be considered before work can be carried out in earnest.

Experience has shown that there are no shortcuts around these steps. The delay in one would drag the others with it. These factors include:

- The prevalence of stability and political tranquility after regime change.

It should be emphasized that in the case of Iraq we are not just talking about a change of government but the forging of a new social contract for a country that has endured much pain and suffering for around a quarter of a century.

- A debate among Iraqis over the new oil policy.

If we assume that the new regime will have a semblance of democracy, then this will mean that there should be a debate about future oil policies, a subject that will remain at the center of Iraqi domestic politics. One can imagine that contending interests, ideologies, and different professional opinions about the course to take to revitalize the oil sector will influence such a debate.

- Some professionals question the wisdom of open and unlimited increase in capacities without proper assessment of world demand and assured access to market at reasonable prices.

It will definitely not be in Iraq's interest to indulge in a price war.

- A definition of the turf for NOC and the IOCs.

One can safely assume that the oil professionals will have an important role to play, but they will want to know up front what the status and role of the NOC will be as well as its relationship with the IOCs. Hence, in a consultative system, it is necessary to build a consensus among civil society about the oil regime the country should adopt.

Any attempt to try to impose one by decree can only complicated matters, delay a conclusive decision, and create a no-win situation for all those concerned.

One suggestion may be that INOC will continue to own and operate existing producing fields. The development of new fields would be awarded to IOCs with the option for the NOC and domestic private firms to participate in accordance with their financial means.

- Reports that individuals from some opposition groups are trying to secure commissions and associations with IOCs in return of services within a new regime should be totally ignored and not encouraged.

It is the responsibility of the two sides to ensure that corruption does not flourish.

- Development contracts signed, initialed, or negotiated since 1991 should be addressed on a case-by-case basis, with possible approval, revision, or annulment, depending on the terms of the accords.

This is necessary since these agreements were awarded on a political and not purely economic basis. Nonetheless, and taking into consideration political reality, a possible scenario would be to encourage holders of present contracts to team up with local private firms and other IOCs and establish new consortiums that will provide finance, technology, and management.

Such new partnerships would enhance the position of a new Iraqi government to widen and diversify its international relations and provide the country's oil industry better opportunities than currently available.

- The holding of an international economic conference on Iraq to deal with the mounting debt, compensation demands, and sanctions is needed before any major international investments can come in earnest.

IOCs not only need relative political stability, oil legislation, and contracts but also stable monetary and fiscal systems. This will be difficult in Iraq with the runaway inflation and debts and compensation demands of around $250 billion.

Regardless of how much oil revenue will be generated, Iraq cannot sustain itself economically without international financial assistance, let alone rehabilitate and develop its oil industry and other sectors. There should be some immediate and serious considerations at international and regional levels to review all claims, debts, and compensation claimed from Iraq.

- Urgent need exists for a new Hydrocarbon Law to facilitate foreign ventures.

Similarly a general review of all laws and regulations passed in the last three our four decades will be required.

- The negotiations with IOCs.

Experience has shown that contracts with IOCs will take much time and effort. This is necessary to ensure there is sufficient planning for the smooth and successful re-launch of the Iraqi oil industry.

However, no less important for the success of a future Iraqi oil sector is the handling of geopolitical issues. This is necessary for a quick and smooth takeoff of the industry as well as reducing political risk and the financial cost involved. Three issues are paramount here.

First, the establishment right from the start of a competitive, transparent, and open level field in the oil industry is a priority. Experience in many Third World countries has shown that corruption and much political interference are the surest ways of stalling the development of the local oil industry. In the case of a future Iraq, there is also the widely held concern that this is a war about oil. It is imperative to dispel this notion and to take the opportunity to build an exemplary model that can be followed elsewhere.

Second, it is hopefully assumed that Iraq will enjoy a stable state of transition towards a pluralistic and democratic state. Civil disturbances will not only cause havoc and plunge the country into chaotic conditions but will certainly delay any serious plans for rebuilding the country and particularly its oil industry. Any form of military occupation will keep the country in continuous turbulence and will cause serious repercussions.

Third, the two issues that have dominated Middle East politics throughout the past decades are the Arab-Israeli conflict and oil. If we are to integrate the Middle East oil industry more effectively into the global economic system and ensure optimum benefits to the local population and economy as well as safeguard the interests of the IOCs, then it is necessary to have peace in the region, and this can only come with the just and comprehensive settlement of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The Middle East is, by every standard, the largest basin of oil in the world. It is impossible to leave oil out of any strategies concerning the present and future of that volatile region.

Originally issued as "Iraqi Oil Policy: Present and Future Perspectives," a special report distributed by Cambridge Energy Research Associates Inc. Reprinted by permission of CERA and the author.

The author

Issam al-Chalabi ([email protected]) was oil minister of Iraq from 1987 through October 1990. Currently a consultant, he was educated at University College, London. He has held a wide range of positions within the Iraqi oil industry.

He was project manager for the Rumaila oil field and the Iraq-Turkey pipeline. In 1975, he took the position as president of the state oil company for oil projects, responsible for the implementation of all oil and gas projects. In 1981, he became vice-president of the Iraq National Oil Co. and, in 1983, deputy minister of oil and president of INOC. In 1987, he became oil minister until relieved of his duties after the invasion of Iraq.

Since 1991, he has been working as a private consultant in the field of global energy with emphasis on oil and gas in the Middle East.