Iranian options most economically viable for exporting Caspian oil

The Caspian Sea region's oil potential has attracted much attention since the break-up of the Soviet Union.

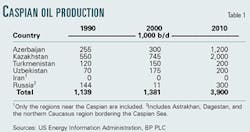

The five Caspian littoral nations—Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Russia, and Iran—are already major oil producers. Their combined Caspian-area oil reserves have been estimated at 16-32 billion bbl. These reserves are located far from potential markets, and thus transport of this oil to international markets has become a critical issue for these countries.

This article outlines some of the proposed options for transporting Caspian oil and assesses their viability.

Given Iran's unique location as a bridge between the Caspian reserves and oil-export capabilities on the Persian Gulf, options for transiting that country, either via pipeline or swaps arrangements, are the most economically viable.

Pipeline options

Most existing oil pipelines in the former Soviet Union depend on Russian transit. These pipelines have operational concerns for shippers, such as blending with the Urals crude that often diminishes the crude oil quality (this is true for all pipelines linked to the Transneft system).

In addition, depending on Russian transit requires tankers to traverse the crowded and ecologically (as well as politically) sensitive Bosporus Strait for access to international markets.

There are also some political and security questions as to whether the newly independent states of the FSU should rely on Russia or any other foreign country for exporting their oil.

The main purpose of this article is to elaborate a comprehensive feasibility study of oil pipelines routes in this region and to find the most economic route of transport. A cost-benefit analysis of the most significant possible pipelines leads to the conclusion that the Iranian option is among the most viable routes. Several findings in our analysis demonstrate that this route is a viable option both economically and from a physical-route perspective.

Beyond the study of route economic feasibility, research into the political dimension of proposed oil pipelines in this region leads to the conclusion that Iran's most significant disadvantage stems from US policies regarding the transit of Caspian oil to international markets.

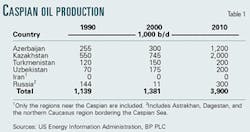

For the longer term, however, the importance of Caspian energy resources when compared with other major sources of energy supply, such as the Persian Gulf, will diminish over time.

Caspian role

After the formation of newly independent states in the Caspian Sea region, the priority for these countries has been the creation of open economies. Energy resources have played a major role in the development of these economies. The desire to get high tariff revenues and to spur competition among international companies, coupled with the political issues of Caspian oil and gas, has resulted in a new situation for the economics and geopolitics of energy in this region.

It is unlikely that Caspian oil supplies will have a significant impact upon world energy markets in the next 5 years because of the following factors:

- There are much bigger oil reserves in Russia, which will limit the other Caspian countries' export access through its territory. Most of the proposed pipelines run across Russian territory or across countries such as Georgia, where Russian influence is strong.

- The lack of clarity on the Caspian Sea's legal status.

- The lack of an integrated energy network in this region.

- All of the Caspian oil pipeline export routes, including those through the Caucasus and potentially to Turkey, are not only costly but also have high political risk.

- The oil export routes terminating at the Russian Black Sea port of Novorossiysk or Georgian port of Supsa require tankers to transit the crowded and ecologically and politically sensitive Bosporus Strait, in order to access Mediterranean and other world markets.

- US energy strategy in the Caspian Sea is increasingly focused on Russia and may deny long-term benefits to the other Caspian countries.

- Despite attempts by major oil importing countries to diversify away from Persian Gulf countries, their dependency on the region still persists. The share of oil imports from the Persian Gulf by Japan, Western Europe, and the US in 1983 was 60%, 41%, and 10.3%, respectively. These shares have grown, to 74%, 50%, and 25.1%, respectively, in 2001. It is expected that this dependency will rise further in the years to come.

Oil export routes

Selecting a cost-effective pipeline route for transporting Caspian oil to international markets has caused heated debate among local and international players in this region.

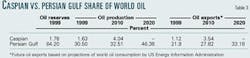

A cost-benefit analysis for assessing economic viability of the various Caspian oil pipeline routes is based on the following assumptions:

- The oil pipelines operate at 70% of their full capacity during their economic life.

- Tariffs are the main source of income from the pipeline for the country of the transit path.

- There are three scenarios for tariffs. One assumes the same tariffs for all routes in the analysis ($2/bbl); the second uses the least-economic tariff rate (sensitive analysis); the third employs official tariffs.

- Oil pipeline costs include three categories: Capital expenditures (Capex), operating expenditures (Opex), and host country expenditures.

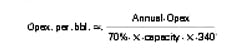

- Opex is equal to 4% of Capex.

null

- The tax rate is 20% of gross profit for all routes.

- Working days total 340 days.

- The discount rate is 10%.

- Allocation of initial investment breaks down as 25% first year, 50% second year, and 25% third year.

- Depreciation equals Capex divided by 21.

The results of this cost-benefit analysis are shown in Tables 4-6.

Iran's role in Caspian oil transport

Considering its geographical position, national politics, and economic interests, Iran has taken steps toward constructive involvement in the secure and cost-effective export routes for oil and gas in the Caspian region.

The port of Neka is located in Mazandaran Province, near the shore of the Caspian Sea in northern Iran. The port functions exclusively as an oil port.

There are eight oil storage facilities (bunkers) outside the port zone, and two oil storage facilities inside. In addition, there is a barge with total storage capacity of 67,400 tonnes. The available pipelines include a 16-in. line used to transport mazut (Russian fuel oil) to the power plant at Neka, and a 30-in., 320,000 tonne/year line used to transport crude oil.

The port limit at its entrance is 120 m and contains five berths. As it is configured now, this port can add only one berth as a dolphin berth. According to recent studies, however, by constructing an eastern breakwater, three other berths could be developed. That makes a total of nine berths that could be available in the future.

Construction of the two new berths with combined capacity of 45,000 tonnes/day would require 51 months and cost $918,250. Developing a dolphin berth inside the port calls for 22 months at a cost of $605,875. Completion of the breakwater would take 40 months, and total project cost, the three berths included, would be $3,617,625.

With completion of the Neka-Tehran pipeline in the near future and by addressing some of the needed changes just outlined, the Port of Neka could become the most suitable, efficient port centered on oil swap operations in the Caspian Sea region.

Compared with other ports in northern Iran (Anzali, Noshahr, and Amir Abad), Neka enjoys, from a time and cost-savings point of view, a number of advantages. It can certainly be developed much faster. If the number of berths were increased to eight, along with the requisite pumping, loading, and offloading equipment, then this port could accept traffic of 16 oil tankers with a capacity of 6,000 tonnes/day each, totaling cargoes that comprise an export capacity of 672,000 b/d of oil.

Costs for transiting Iran

In the current situation, the countries of the Caspian region produce 2 million b/d of oil.

Iran's governmental and private sectors could play a crucial role in swapping oil as well as in transiting oil from the central Asian republics of the FSU.

In terms of swapping oil, Iran would import the required oil for its northern refineries and would deliver the same quality and volume of oil to its clients via the Kharg oil terminal in the Persian Gulf.

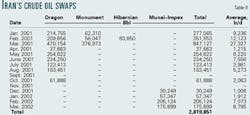

One of the Iranian companies active in swapping oil is Naft Iran Co. (NICO), which in Tehran works through a trading services unit, Sahand Naft Iran Ltd. This company is an affiliated company of Iran's petroleum ministry and is active exclusively in trading and swapping oil from the FSU.

It's useful to recall that the combined capacity of Iran's major northern refineries—at Tehran, Tabriz, Isfahan, and Arak—would be 600,000-700,000 b/d, depending on proposed near-term upgrades. If the exports of oil to Iran exceed that level, then there would be an economic justification for constructing a direct pipeline from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf.

The costs of transiting oil via Iran include:

- Capex, such as constructing a new oil pipeline, building new oil terminals, and extension or expansion of existing pipelines.

- Opex, such as management, personnel, pumping costs.

- Transit fee.

- Financing costs, notably repayment of loans and interest.

On the basis of calculations by Iran's petroleum ministry, the costs of transporting oil by tankers, across the Caspian Sea to Neka Port, are shown in Table 7.

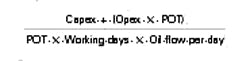

To calculate the cost of transport per barrel of oil, the following formula is used:

null

The per-barrel costs of transporting oil via Iran using variously sized tankers are also shown in Table 7 and indicate that the most efficient option is to use 40,000 dwt tankers.

Table 7 also shows the costs of transporting 350,000 b/d via Iran by pipeline, broken out by pipeline diameter.

Iran has a unique geographic situation and suitable infrastructure necessary for transferring oil from FSU countries to Asian and European markets. There are three options recommended for swapping oil via Iran:

- Option 1. In this phase, crude oil from Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan can be transferred to the northern ports of Iran such as Neka and Noshahr, then shipped to the Tehran and Tabriz refineries. The next step is to deliver the same volume of oil to the client at the southern Iranian oil terminal. The projected capacity for the 350 km pipeline from Neka to Tehran is 370,000 b/d. The cost of constructing this pipeline would total $450 million: $250 million for the pipeline and $200 million to upgrade the refineries.

- Option 2. In this option, the refineries at Isfahan and Arak would be used to swap crude oil. This way, Iran would be able to transfer 450,000 b/d from the eastern or western sectors of the Caspian Sea to Tehran by pipeline. One alternative would be to reroute the pipeline from Tehran-Isfahan to Tehran-Arak.

- Option 3. This option includes a direct transfer of oil from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to the Kharg oil terminal in the Persian Gulf. The important point is that the current loading and offloading capacity at the Kharg terminal is more than 5 million b/d. In addition, Iran is considering the construction of one or two refineries in northern Iran to provide 200,000 b/d of additional capacity. Currently, effective refinery capacities are Tehran 220,000 b/d, Tabriz 110,000 b/d, Isfahan 110,000 b/d, and Arak 150,000 b/d.

Crude swap challenges

At present, other oil export routes, especially routes north through Russia that feature relatively attractive transit costs and the support of the US, compete with Iranian routes. Therefore, decreasing all costs of transiting oil via Iran should be considered by the relevant organizations.

One of the main issues that has surfaced since 2001 is the problem of the decreased draft of the Port of Neka. According to the reports of the oil and gas division of the Caspian Sea department of Iran's petroleum ministry, the berth depth at Neka Port shrank by 25 cm as of spring 2002 from its level in May-June 2001. Over the past 5 years, the berth depth has declined by a total of 50 cm. In spite of the dredging carried out at Neka and the depth of 6 m in the center of the port's bay, the depth of water at the berth is 3.25 m. This is not suitable for ships of 5,000 dwt. So for the first option and to accommodate the existing fleet, the water depth at the berth needs to be at least 4.5 m.

Another important issue is the quality of oil received from Kazakhstan. Because Kazakh crude oil has a high sulfur content, it would require extra costs to upgrade Iranian refineries in order to refine this kind of crude.

The economic justification of the Neka-Tehran pipeline depends on a throughput capacity of at least 370,000 b/d. Thus shipping Kazakh oil via this line is highly important.

Finally, the lack of a clear legal regime in the Caspian Sea has caused a delay in the development of some oil and gas projects in this region, which must be taken into consideration regarding transportation planning.

Outlook

Western Europe and Asia will remain heavy importers of oil and gas from the Persian Gulf, and this region with its massive resources will remain the most viable supplier of crude oil to those regions, irrespective of claims about Caspian energy potential.

At the same time, however, Iran will have to play a significant role in facilitating Caspian energy development because of the following factors:

- Iran's population centers are mainly located in the north, near the other Caspian countries. About 55% of Iran's population is under the age of 20. The rapid rate of urbanization resulting from such a young population has brought greater pressure on government not only to create employment opportunities but also to accommodate the residential and commercial demand for energy. In this respect, northern Iran can be a major oil importer from the Caspian region.

- The total capacity of Iranian refineries in the north is projected to exceed 800,000 b/d.

- The young and growing population guarantees a stable and growing demand for Azeri, Kazakh, and Turkmen oil.

Iran is geographically a bridge between the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf and is the only country in the Middle East that can play this unique role.

The feasibility study for oil pipelines that underpins this article demonstrates the viability of the Iranian option in order to transit and swap Caspian oil to Asian, European, and, eventually, US markets.

The author

Mohammadreza Farzanegan ([email protected]) is a senior expert in transit and special economic zones for the general directorate of Iran's Ports & Shipping Organization. He has a masters in energy economics from Tehran University.