Average Asia refining margins deteriorated in 2002 from previous year levels. The last quarter of 2002 was an exception, however, which could be a turning point for Asia refining margins.

Last year could mark the low point for refining margins in Asia. Crude prices are likely to settle in a lower range because current prices are not sustainable, given lower demand growth rates for petroleum products. Furthermore, the current war premium will erode after resolution occurs in Iraq.

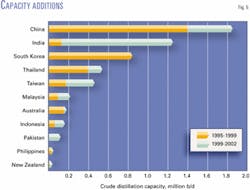

Asia has had some significant additions in refining capacity during the last 5-6 years; refining capacity increased nearly 35%. Most of these additions were in China, India, and Taiwan.

Most of these projects materialized when Asia demand growth started weakening. This has affected regional product balances and refining economics because surpluses resulted, which lowered refining margins.

Any recovery in refining margins, however, hinges on:

- Improved demand growth in the short to medium term.

- The pace and extent of deregulation in the protected Asian markets in the long run.

A significant proportion of Asian refiners operate with some sort of protection. This protection might be a differential between crude and product import duties, an assured rate on investment, or a guarantee that domestic products are consumed before imported products.

These refiners maintain relatively higher utilization rates, even when regional markets have a surplus of products and free-market margins are negative. This situation worsens refining margins even more.

Asia refining margins

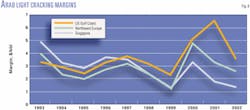

Gross refining margins in Asia based on cracking yield for Dubai crude decreased to $0.76/bbl in 2002 from $1.25/bbl in 2001; however, margins based on hydroskimming showed a slight improvement due to higher prices for high-sulfur fuel oil (HSFO).

Persistently high crude prices and weak product demand growth were the main causes of lower margins.

During first half 2002, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) held official production quotas unchanged, which kept prices high. After that, a significant war risk premium helped increase prices; in recent months the situation has been exacerbated by the Venezuelan crisis.

Fourth quarter 2002 was an exception; refining margins based on cracking yield averaged almost $2/bbl in fourth quarter 2002, compared with $0.76/bbl for all of 2002.

Similarly, there was a substantial improvement in margins for hydroskimming yields (Fig. 1), the result of a sharp increase in product prices through fourth quarter 2002. Naphtha, kerosine, and diesel prices increased substantially in the third quarter, primarily due to an early winter in northeast Asia that resulted in higher heating oil demand.

The recovery may not, however, be sustainable. So far, Asia cracking margins averaged nearly $3/bbl through January 2003. A long-term recovery in refining margins must be supported by stronger growth in oil product demand from the rest of the region.

Also, low-sulfur waxy residue prices rose sharply as Japanese power companies resorted to burning oil due to the closure of nuclear plants.

Concurrently, direct crude burning resulted in higher Indonesian crude prices. The Minas premium increased to $4-5/bbl vs. Brent, and $2-3/bbl vs. Tapis, which made heavy sweet crude even less attractive for refining than in the past.

Historic perspective

Asia experienced substantial refining capacity growth during the last few years.

Based on crude distillation unit capacity, the refining capability of Asia increased at an average growth rate of 4.3%/year in 1995-2002. This is particularly remarkable because during the same period total oil product demand increased at only 2.6%/year (Fig. 2).

In 1995, Asia refining capacity was more than 16 million b/d, with middle distillate net imports of more than 800,000 b/d. Lighter product (LPG and naphtha) net imports exceeded 1 million b/d.

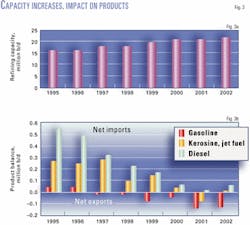

The first wave of additions increased Asia's refining capacity to 17.9 million b/d in 1997. Another 3 million b/d were added during the next 3 years. By 2000, the region's refining capacity was just less than 21 million b/d, and currently stands at 21.8 million b/d.

These additions have transformed several major importers into major exporters, and the region's refining margins deteriorated substantially. By 2000, net imports of middle distillates were slightly higher than 100,000 b/d. The region also became a net exporter of gasoline (Fig. 3).

These developments were perhaps most obvious in India, where refining capacity doubled 1995-2000. India transformed to an exporter of around 40,000 b/d of middle distillate in recent years from an importer of 300,000 b/d in the mid-1990s (Fig. 4).

Refiners planned these capacity additions when domestic oil product demand was growing by more than 5-6%/year. When the additions came online, however, growth had slowed to less than 1%/year. This forced Indian refiners aggressively to seek markets for these products outside India.

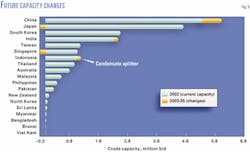

During the first wave of additions (1995-99), many countries—specifically China, South Korea, and Thailand—added refining capacity (Fig. 5).

The second wave started in 1999 when India added more than 1 million b/d of capacity, followed by China and Taiwan. These plants include India's Reliance Petroleum Ltd. refinery at Jamnagar, several refineries in China, and two Formosa Petrochemical Corp. plants in Taiwan.

These additions coincided with relatively weaker demand growth in Asia, which started in early 2000. Product surpluses and a deterioration of refining economics caused Asia margins to be the lowest of the three major refining centers.

Asia refining margins were not always so poor. Before 1995, Asian margins were better than those of the US and Europe (Fig. 6).

US refining margins experienced a sharp increase in 2001 because acquisition prices for Arab Light crude dropped by 33% in the last quarter. This decrease was more than the decline for Asian and European markets.

Regulated markets

A substantial portion of Asia refineries operate with some sort of government protection; 36% are somewhat protected and 48% are completely protected. Only a small portion operates in a completely free-market environment.

- Completely protected. Refiners operating in a completely protected environment receive protection via the structure of import duties on crude and products. Even with negative refining margins in free markets these refiners, such as those in India, China, and Taiwan, can enjoy positive and even healthy margins. Import duties for products and crude differ by 6-8%.

Protected refiners include those that receive a guaranteed rate of return or a guarantee for the sales of their products, like refiners in Pakistan. Indonesian refiners do not operate based on revenues, but rather on a cost-plus-fee basis. As such, protection does not really matter.

- Free-market operators. About 16% of Asia refining capacity operates in completely free markets, free from any sort of controls or protection. There are low or no duties on petroleum imports. Examples include refiners in Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, and the Philippines.

- Somewhat protected. Refiners in this category operate between free-market and completely protected systems. These refiners do not have the protection of a formal tariff-based mechanism; the market structure makes it difficult to build new refineries or import products.

For example, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have storage requirements that make imports difficult for nonrefiners. Japan also has some structural constraints on the size of refined product cargoes its ports can handle.

Import storage requirements act as barriers to entry; conversely, once an importer has built an infrastructure, the same requirement acts as a barrier to exit. The initial intention of providing protection to refiners, therefore, turns into long-run entrenched competition against them.

For instance, in South Korea independent imports as a percentage of total oil product demand have increased substantially, forcing refiners to restrain crude runs and lower domestic prices. Refiners in South Korea have started lobbying for an increase in the product-crude differential to 7% from the current level of 2%.

Protected refiners can afford to run at high utilization rates even when Singapore margins are depressed; therefore, they have an advantage vs. refiners operating in a free market.

- Different markets warrant different configurations. The three major factors that determine the appropriate configuration for a particular market are demand barrel, crude diet, and refined product specifications.

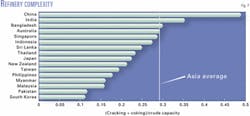

Based on conversion capabilities, Asia refiners range from high conversion-to-distillation ratios such as China and India to low ratios such as Pakistan and South Korea (Fig. 7).

China, due to heavy domestic crude (average 31°API gravity), needs substantial cracking-conversion capacity to match its demand barrel.

India, despite lighter domestic crude streams, needs a higher conversion capacity due to a substantially lighter demand barrel and heavier imported crudes. Furthermore, the recent addition of the Reliance refinery, which accounts for almost 25% of the country's refining capacity, has increased India's conversion capability.

South Korea and Pakistan are on the other end of the scale. Pakistan has a relatively heavier demand barrel; therefore a simple hydroskimming refinery is sufficient for its market.

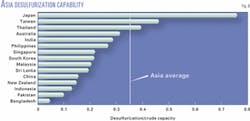

A market's treating and desulfurization capability is a good barometer of the prevailing and planned product specifications and the level of sulfur in the crude diet.

Japan is an extreme example. Refiners there are equipped to process one specific type of high-sulfur crude while making products to specifications that are the most stringent in Asia. Japan has the highest treating-to-distillation ratio in Asia.

On the other extreme are Indonesia and Pakistan, where product specifications are relatively less stringent (Fig. 8). Most of the Indonesian crude diet is low sulfur and the country currently uses 0.5% sulfur diesel with no apparent plans to upgrade; similarly Pakistan currently produces 1% sulfur diesel from domestic refineries and 0.5% sulfur diesel for imports.

On the other hand, Japan requires 0.05% sulfur diesel and plans to move to 0.005% sulfur by 2005. India, Taiwan, Thailand, and the Philippines have some of the most aggressive plans to upgrade fuel specifications. This is reflected in their high treating capabilities.

Asia and the Middle East

Asia is a major importer of LPG and naphtha from the Middle East, which will likely continue. In the long run, Middle East refiners will find it relatively easy to sell light products; however, the situation is slightly different for middle distillates, which remain in relative surplus. Asia's net imports of diesel and kerosine-jet fuel have declined during the last several years.

Export-oriented refiners in Asia and the Middle East will compete in Indonesia, Pakistan, Viet Nam, and smaller markets like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh for middle distillates. China and India were big importers of diesel; however, they stopped some time ago, achieving the status of middle distillate net exporters.

Middle East refiners have recently lost some traditional markets in Asia to other refiners within Asia that benefited from lower freight costs and the ability to meet stringent product specifications.

Refiners in the Middle East are focusing on quality-based additions, an area in which they have fallen behind.

Bahrain Petroleum Co.'s Sitra refinery is adding a 70,000-b/d middle distillate treater that will enable the country to manufacture 10-ppm diesel for export.

Iran refiners are undertaking several similar projects that will improve gasoline and diesel quality. The country is currently short of unleaded high-octane gasoline and, therefore, must import from India. Iran plans to impose a 50-ppm diesel standard throughout the country.

Kuwait has almost completed repairs on its largest refinery, Mina Al-Ahmadi, and has initiated middle-distillate treating projects at Mina Al-Ahmadi and Mina Abdullah. When the projects are complete, Kuwait will have the highest treating-to-distillation ratio in the Middle East region.

Changing ownership

Table 1 shows that nearly one-fifth of Asia's refining capacity is owned by international oil companies—ExxonMobil Corp., Shell Oil Co., ChevronTexaco Corp., and BP PLC. The international oil companies have merged some refining operations. One example is the Map Ta Phut, Rayong, Thailand, refinery operated jointly by Caltex (ChevronTexaco), Shell, and PTT PLC.

Consistently lower refining margins have forced some of these companies to reassess their positions in the refining sector, which will result in some shuffling of the ownership structure.

For example, PTT may sell its share in Thai Oil Co. Ltd.'s Sriracha, Rayong, and Star refineries. BP has also decided to sell its share in a Singapore refinery. ChevronTexaco is evaluating its refining assets worldwide and might sell off some of its Asia assets.

Shell's Clyde and ExxonMobil's Port Stanvac refineries in Australia have been slated for closure for some time. It is currently more viable for the companies to keep running the plants due to high closure costs. Both refineries are likely to close by 2008, if not earlier.

After the 1998 financial crisis in Japan, about 270,000 b/d of refining capacity was shut down. More recently, an additional 160,000 b/d was mothballed and more closures are on the way.

Idemitsu Kosan Co. Ltd. will shut down its Hyogo refinery in April 2003 and its Okinawa refinery in April 2004. Also, Nippon Oil Co. Ltd. plans to shutter 10,000 b/d of refinery capacity this year. These closures will involve about 200,000 b/d.

These changes will alter the current ownership structure of Asian refining capacity.

Outlook

No substantial additions are planned for Asia refining during the next 3-4 years:

- China will continue to add refining capacity.

- A small hydroskimming plant will come online in Pakistan.

- Reliance will debottleneck its Jamnagar plant, which will add 112,000 b/d of crude distillation unit capacity.

- A 100,000 b/d condensate splitter will start up in Indonesia.

Japan will continue to reduce some of its refining capacity (Fig. 9) and some closures or mothballing is likely in Singapore and Australia in the long run.

Poor refining margins characterize the current state of refining in Asia; this has resulted in several refining plans being put off until economics improve.

Last year will most likely have been the bottom for Asian refining margins because currently high crude prices are not sustainable with relatively weak demand growth. The war premium on crude prices will erode once the Iraq issue is resolved.

Refining margins will recover slowly; however, it will depend on revived oil demand growth and continued rationalization of refinery utilization rates.

The authors: Hassaan Vahidy is a senior associate for FACTS Inc. and currently serves as the lead analyst of the company's Singapore office. His research focuses on the downstream oil and gas industry in the Middle East and Asia Pacific. Prior to this position, Vahidy worked for Royal Dutch/Shell in Pakistan. He holds an MA in economics from the University of Hawaii.

Fereidun Fesharaki is president and founder of FACTS Inc., Honolulu. He is also a senior fellow at the East-West Center, Honolulu. He is the author or editor of 23 books and monographs and numerous technical papers on energy issues. His work focuses on downstream oil markets, OPEC policies, and Asia-Pacific oil and gas markets. Fesharaki received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey, England.