Asia-Pacific gas faces more competition, seeks new markets

Asia-Pacific natural gas faces many new challenges and opportunities.

While competition for Asian markets continues from Middle East LNG, the Asian consumption outlook remains positive as clean-burning natural gas displaces petroleum and takes new market growth.

New contractual systems underlie new plants as deregulation has led to reliance on cost competition in lieu of committed price-volume contracts, a competition that Asia-Pacific producers can win. Gas liquids prospects continue strong as LPG demand, petrochemical growth, and a lighter Asia-Pacific demand barrel focus attention on light petroleum liquids. Looming shortfalls in North America present the opportunity for new markets for Asia-Pacific producers.

Resources

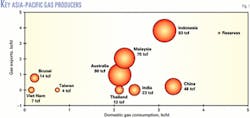

Across Asia, gas reserves are plentiful. Unlike the US, Asia's gas issues are related not to supply but rather to demand and infrastructure development. Fig. 1 illustrates the consumption and reserves of gas in key gas-producing Asian countries. Important Asia-Pacific gas producers such as Malaysia, Indonesia, and Australia cannot consume nearly as much as they produce and hence must export.

Reserves in Asian countries are plentiful to meet not only current but also expanded consumption. Reserves-to-production ratios average more than 40 years (Table 2).

Asian countries as a whole are incompletely explored. Opportunities exist for expanding reserves, but there is limited incentive to do so without timely prospects to monetize known proven reserves.

LNG supply

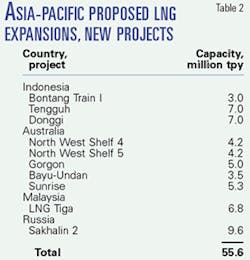

Four nations—Indonesia, Malaysia, Australia, and Brunei—account for all Asia-Pacific LNG exports. Russia seeks to enter the market as a new Asia-Pacific LNG producer (Table 3). Each faces slightly different issues in expanding LNG trade.

Indonesia and Australia are best situated from a reserves point of view. Both countries have some brownfield expansion capability but also distant reserves facing the prospects of greenfield investment economics.

Indonesia's oil and gas sector faces uncertainty due to national issues, fundamental regulatory changes, and modifications in the role of state oil company Pertamina that have yet to play out. While these changes have yet to deter expansion of the major LNG plant at Bontang, local unrest in 2001 interrupted production at the Arun LNG plant.

There is evidence that political risks played a role in China's selection of competing Australian LNG over Indonesia for supplies to the developing Guangdong LNG terminal near Hong Kong.

Pertamina's new role as competitor instead of participant and regulator has led to the promotion of the new Donggi project in Sulawesi, with reserves controlled by Pertamina, in addition to the Tengguh project in West Papua (formerly known as Irian Jaya), which is controlled by a BP PLC-led group.

Australia is blessed with a stable government and plentiful reserves but has problems of high cost and distance from many markets. The Northwest Shelf project is expanding into a fourth train with plans likely for a fifth train.

Outside the Northwest Shelf, Australia has many project opportunities in offshore waters. The ChevronTexaco Gorgon project would tap a large gas reserve off Barrow Island. Further north, the Timor Sea area includes ConocoPhillips' Bayu Undan project, which has been tied up pending resolution of a joint development treaty between Australia and recently independent East Timor. The nearby Sunrise project is planned as the world's first floating LNG plant.

In Malaysia, LNG Tiga is a two-train expansion of the Malaysian LNG complex near Bintulu, each with a capacity of 3.4 million tonnes/year (tpy). Brunei would like to build a sixth train later this decade but as yet needs to prove up adequate gas reserves.

In Russia, the Sakhalin 2 project, led by Royal Dutch Shell Group, involves a mammoth two-train LNG complex at 9.6 million tpy.

Huge hydrocarbon resources have been discovered on Russia's Sakhalin Island. Two groups, one led by ExxonMobil Corp. and one by Shell, seek to bring these resources to market. Shell's Sakhalin 2 project centers on an LNG plant oriented toward the Japanese market, while Sakhalin 1 would target much the same market using pipeline technology.

There is no shortfall of Asia-Pacific gas reserves or LNG project ideas. Why are these projects taking so much time?

Development issues

Three factors constrain Asia-Pacific LNG developments: competing supplies from Middle East LNG projects, demand levels in economically accessible markets, and contractual and national factors related to project risk.

Competing supplies

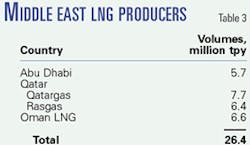

Middle East producers have access to even more plentiful gas reserves than Asia-Pacific producers. While Middle East reserve figures are notoriously unreliable, unconstrained as they are by even the loosest requirements for uniform reporting standards, there is no doubt that reserves in Qatar and Iran in particular are massive and adequate to support even the most ambitious LNG programs.

Over the past decade Middle East LNG suppliers (Table 4) have made important inroads in supplying traditional Asian LNG markets in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Middle East suppliers have some geographical advantage accessing parts of the South Asia market, particularly the west coast of India. These competitors will not surrender markets to Asian producers and remain extremely important competitors.

New Middle East projects dwarf many of the Asian projects. Qatar proposes to quadruple its production over the coming decade, accounting for perhaps 50-55 million tpy of new production by 2010. Similarly Iran's South Pars projects include up to four LNG projects producing perhaps 30 million tpy in aggregate.

Fortunately for Asian LNG producers, consumers still prefer a mix of suppliers, and Asian producing locations are favored geographically for most Asian ports. Shorter shipping distances partially offset advantages enjoyed by low-cost Middle East producers.

Further, plant-expansion economics are available at many locations in Asia, while some prospective Middle East producers would be saddled with grassroots LNG costs.

Even though new Middle East LNG production often targets European consumers, it affects Asian markets.

Middle East LNG production can serve new demand in Europe and potentially in the US. Although Middle East producers have contracts with consumers in Japan and Korea, they are at some shipping-cost disadvantage in those markets as compared to Asia-Pacific LNG supplies.

Middle East suppliers have a logistical advantage in serving parts of India, but that market's potential isn't large enough to consume LNG produced in the Middle East. Consequently, new Middle East projects tend to be focused in the larger markets West of Suez.

Nevertheless, Middle East projects hold the potential to influence LNG markets in Asia by holding a large segment of supply available to prospective buyers.

Available markets

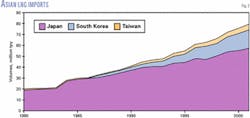

Historical Asian LNG demand has been in exactly three countries: Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Fig. 2 shows historical Asian LNG import demand.

Still accounting for the preponderance of Asian LNG demand, Japanese demand growth has slowed. In Japan, LNG is used principally for power generation and also for town gas. Power-generation demand growth from existing customers has slowed.

One source of demand growth is the liberalization of power and gas markets that allow progressively smaller consumers to select new energy suppliers. That program has led to erection of gas-fired independent power producing (IPP) plants but, as will be explained presently, is a two-edged sword with respect to LNG.

Gas consumers in Japan are connected to town gas systems. Unlike the US or Western Europe, these systems are not connected into a national gas grid, although some systems have limited interconnections for supply security reasons. Generally each company wishing to buy LNG must invest in access to offloading, storage, and regasification facilities. Some companies, for example Tokyo Electric and Tokyo Gas, may share facilities, but because there is no long distance pipeline transport, that doesn't help the smaller systems in more distant locations.

Many smaller systems continue to rely on alternatives to LNG and may not have sufficient demand to justify interconnection.

Korean LNG demand is highly cyclical with strong wintertime demand falling to lows each summer. Unlike other Asian nations, Korean gas demand is dominated by space-heating demands in the residential-commercial sector.

Most likely Korean demand will continue to grow as gas reaches more consumers and power producers reap the benefits of new, lower-cost LNG supplies. Like Japan, Korea is in the process of liberalizing markets currently dominated by sole importer KOGAS.

Taiwan is the smallest existing Asian LNG market and consumes LNG principally for electrical power generation. While Taiwanese LNG consumption has grown rapidly, albeit from a small base, the outlook is driven mostly by concerns about alternative sources of electrical power. Taiwan's chief alternatives to LNG for power generation are nuclear energy, coal, and petroleum.

Nuclear energy has acquired negative political connotations in Taiwan, similar to those in the US but perhaps not quite so severe, which are deterring new nuclear plant construction. Emissions from coal-fired power plants deter new construction of those plants. LNG can compete successfully with oil-fired generation in Taiwan.

New Asian LNG markets are emerging. China and India have captured the greatest attention, but LNG is seeking to penetrate the Philippine market also. Even Indonesia may become an LNG consumer if LNG technology is used, as proposed, to transport gas from distant production areas to heavily populated Java for consumption.

As the Table 4 illustrates, demand growth once was centered on the three large historical consumers. Those, as a group, will continue to account for substantial LNG growth, but the emerging consumer group will make a significant difference through 2010.

A new potential bright spot for Asian LNG producers has emerged on the West Coast of North America. While gas demand has continued to grow in the US, gas production has fallen, and North America will become a more regular, higher-volume LNG importer in the coming decade.

Of course, the US has several key alternative import locations, including the East Coast, Gulf Coast, and West Coast sites. The most interesting sites to Asian producers are those in California and nearby Baja California. Baja sites hold the promise of avoiding troublesome regulatory stalemates that have plagued so many California energy projects over the past 20 years.

As US gas producers undertake their own efforts to bolster production, the market will look not only to conventional suppliers but also to new sources of gas including Asian LNG. Work Purvin & Gertiz is undertaking now is helping to define the magnitude of LNG import opportunities as well as optimal locations.

Contractual, financing matters

Contractual issues hold the potential to emerge as important new factors in Asian LNG expansions. Price and conventional contract terms such as point of sale are important.

Perhaps more important, however, is the influence of deregulation in traditional off-taking nations and legal structures in the emerging markets.

Competition from Middle East suppliers as well as among competing Asia-Pacific LNG producers and evolution toward lower cost and larger trains have triggered some movement toward lower prices. LNG prices in relationship to oil products have been trending downwards. That movement has been facilitated by reduced costs at all steps of the value chain that make such lower prices possible.

More importantly, perhaps, new buyers have been demanding and, in the face of an abundance of sellers, receiving superior contract terms.

Historically, LNG contracts bound each contract to purchasing for a single destination port usually on an ex-ship basis. Buyers received little or no unilateral flexibility to divert or resell shipments.

Recent contracts have provided for far more flexibility, and new contracts provide for far more volume to be sold on an FOB basis. Hence buyers are gaining new opportunities to capitalize on shortfalls and participate in the emerging LNG spot market.

Historically, LNG production plants have been financed based on a foundation of reasonably reliable take-or-pay contracts with financially sound consumers. Over the years, that form of financial support has diminished due to several factors. The ability of even those historical customers to sign such contracts has been compromised.

In all cases, historical Asian LNG customer companies are subject to one form or another of emerging deregulation and competition. While they once were able to pass on price risk to captive customers, those customers now are able, at least in principle, to seek less-expensive energy from other suppliers.

Each passing year sees expansion of competition opportunities to smaller off-takers. In fact, most historical consumers have not taken advantage of such supply opportunities. Nevertheless, customers are aware of new, less expensive supply opportunities and pressing for hitherto unthinkable price concessions. In these circumstances, LNG off-takers cannot simultaneously promise both price and volume.

Under a deregulated system, a take-or-pay contract at formula price carries limited long-term assurance for the supplier. If the contract price is too high, the buyer may be forced into a long-term money-losing proposition. The likely outcome is a contract renegotiation at lower prices.

More commonly, recent contracts have been far more flexible and shorter term to reduce risk for the buyers. This flexibility, however, and these shorter terms transfer risk back to the LNG producer which is no longer assured under new contracts 20 years of off-take at prices adequate to pay off loans. For project financiers, careful analysis must determine how much market and price risk is being absorbed by the project and by the lenders.

The second problem area is the situation of the new off-takers.

Historically, LNG projects were undertaken on the basis of predictable consumer volume from more or less identifiable companies. Regulatory structures were in place to handle the LNG industry before financing was committed. More recently, LNG projects have been implemented without benefit of such arrangements in advance.

India is a key new Asian LNG off-taking nation. The Dhabol debacle is still in recent memory and provides some impetus for taking superior steps to ensure against a repeat. An important step in consideration of new Indian projects will be to ensure that the gas is fundamentally competitive at the burner tip vs. prevailing local oil prices rather than to rely solely on take-or-pay contracts or government guarantees.

LNG volumes are to be delivered into India in the near future, and as yet the industrial and power consumers are not committed. Success under these circumstances is possible but perhaps not assured.

India is a large energy-consuming nation with a substantial unsatisfied demand for clean-burning natural gas. Committing LNG construction projects in this environment, however, departs from the established paradigm of LNG project development.

China is another key new Asian off-taking nation. That country is a voracious energy consumer and requires expanding supplies of energy in all forms. It would consume not only LNG in Guangdong and Fujian but also proposes to build extensive infrastructure for the West-to-East Pipeline among other projects.

China is in the midst of transforming its energy economy towards more competition and open markets at the same time that these LNG and pipeline projects are being implemented. While there is appropriate ground for considerable optimism regarding China, that should be tempered with recognition of what must be accomplished to make energy projects commercially successful.

Important steps are being implemented to mitigate problems.

First, off-takers are becoming more likely to be investors in the LNG production facilities. With an interest in the production facility, some risk is transferred back to the off-taker.

Second, revenues from co-product NGL streams are being used to underwrite loans. By committing NGL or condensate sales at least on a contingent basis as the source of loan repayment, lenders gain greater assurance and part of the risk is mitigated.

Third, emerging consuming nations are working diligently in the midst of the rush to develop new energy supplies also to seek appropriate regulatory and pricing regimes.

The author

John H. Vautrain is vice-president and director of Purvin & Gertz Inc., Singapore, which he joined in 1981. Previously, he had gained industrial experience with Phillips Petroleum Co. and Union Carbide Corp. He was manager of Purvin & Gertz's office in Long Beach, Calif., 1987-2000, was elected director of Purvin & Gertz in 1997, and has been based in Singapore since 2000. Vautrain holds a bachelors in chemistry from the University of Texas and a masters in chemical engineering from the University of Utah. He is a member of the International Association for Energy Economics, SPE, and AIChE.