Russia's gas production, exports future hinges on dramatic changes needed at Gazprom

Russia controls immense reserves of natural gas, but the country faces problems of a comparable magnitude to bring them to market.

Russia's proved natural gas reserves are now estimated at 46.9 trillion cu m (tcm).1 This clearly places Russia at the top of the world's gas reserves list; second-ranked Iran controls less than half that amount.

Russian gas reserves account for almost a third of global reserves estimated at 154.4 tcm.2 It follows that Russia is bound to play a major role in the worldwide gas industry for decades to come.

But can it develop new gas fields fast enough to reverse a recent output decline?

Much will depend on state-owned OAO Gazprom, a company dominating Russian gas and facing one of the most challenging projects in the world: the Yamal-Europe pipeline.

And while still in its "consolidation phase," Gazprom will have to tackle expansion too—no easy overlapping act.

Other Russian companies are keen to develop gas reserves, but they lack Gazprom's experience and critical mass in Russia's gas industry.

So it follows that the future of Russian gas will be linked, for better or worse, to Gazprom's fortunes.

Production trends

Late in the second half of the 20th century, Russia had come to rival the uncontested leader of the global gas industry: the US. It was in the early 1980s that the then-Soviet Union eventually surpassed the US in its production of natural gas.

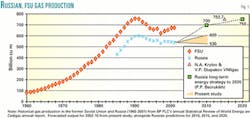

In the years since then, not only did the USSR hold onto first place, but the Russian Federation alone produced more gas than the US. However, the surge in Soviet gas output during the 1980s could not be sustained during the 1990s (Fig. 1). After a brief decline during the first half of the 1990s, Russian gas output eventually stabilized at 540-550 billion cu m (bcm)/year during the decade's second half.

In contrast, US gas production was on the increase during the same period, so it eventually caught up with Russia and, by 2000, both countries were each producing 545 bcm/year.

In 2001, however, the US surged ahead with output of 549.6 bcm3 vs. 543.4 bcm for Russia4 (677.3 bcm for the whole former Soviet Union). Nevertheless, Russia still accounted for 22% of global gas production of 2.464 tcm for 2001.5

Of the still-considerable Russian gas production that year, almost two thirds was consumed domestically and the rest was exported either to Europe or other FSU states (Table 1).

Domestic consumption

Russia's internal gas consumption was initiated on a large scale in 1947, when the first major gas trunkline to Moscow was commissioned.

By 2001, domestic consumption had risen to 373.7 bcm/year. One of the main reasons behind this massive internal consumption was the relatively low price of gas in Russia—in 2001, only $0.43-0.45/MMbtu.6 This price is one seventh to one eighth that of average export gas prices in Western Europe—which, in turn, are linked to oil product prices, albeit with a 9 month delay.7

Russia's energy minister, Igor Yusufov, has repeatedly called for a 35% increase in domestic gas prices for 2002,8 but the government approved only a 15% hike from July 1, 2002, onward for both industrial and residential tariffs.9 The timid increase might well be too little to help stem galloping internal demand for gas, already making up some 55% of Russia's primary energy needs and around 80% of Russian power generation.10 It might also prove too little for allowing Gazprom to rely on domestic revenues to finance some of its mega- projects.

And while consumer debt to gas companies has almost halved in the past 2 years, Russian users still owe 44.9 billion rubles ($1.44 billion) for past deliveries; moreover, only 29 of the 89 regions in the Russian Federation are up to date with their gas bill payments.11

Russian gas exports

The Soviet Union began exporting natural gas in the late 1960s. By 1972, yearly exports already stood at 5 bcm and rapidly grew to 57 bcm by 1980.12 These exports were mainly directed towards Western Europe and the Soviet satellite states in Eastern Europe, as well as others in the FSU.

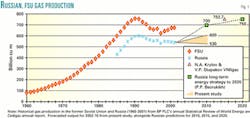

As a direct consequence, after the implosion of the Soviet Union, these two main export trends remained within Russia's gas agenda: the one to Europe and the other to FSU countries. Since 1996-97, Russian gas exports to Europe have plateaued at 120-130 bcm/year. As can be seen in Fig. 2, Western Europe takes the lion's share of these exports, while Central and Eastern Europe account for the remainder.

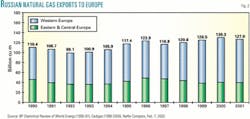

Within the FSU, the major gas customers are Ukraine and Belarus, with Lithuania coming in a very distant third. As illustrated in Fig. 3, exports to the rest of the FSU also have come to stabilize at 80 bcm/year since 1996-97. All told, total Russian gas exports currently add up to 204 bcm/year.

Russian gas reserves

Russia continues to hold to its longstanding idiosyncratic way of estimating reserves in general and gas reserves in particular. It will take some time for Russia to align itself with Western ways of assessing mineral reserves. Until then, one will have to make do with Russian methods and classification.

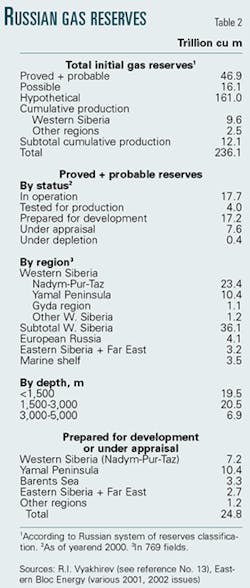

In Table 2, a synopsis for Russian gas reserves is presented based mainly on estimates proposed by former Gazprom Chairman Rem I. Vyakhirev and the monthly publication Eastern Bloc Energy. It shows that Western Siberia at 77% contains the largest share of these reserves.

Within Western Siberia, the Nadym-Pur-Taz region and the Yamal Peninsula clearly dominate, with 50% and 22%, respectively, of total Russian gas reserves. As for the "hypothetical reserves" of 161 tcm mentioned by Russian experts, they should be approached with extreme caution, as they are not supported by geological evidence.

Main Russian gas fields

Russia has a rather unique wealth of major gas fields. As shown in Table 2, currently identified reserves are concentrated in 769 major gas fields.

As usual in the oil and gas industry, a list of these fields forms a pyramid; at its top are the supergiant fields (fields with reserves exceeding 1 tcm), and below that, the giant fields (fields with reserves totaling 0.5-1.0 tcm).

According to reliable industry sources, Tables 3a and 3b show that Russia has at least 11 supergiants (with combined current reserves of 24.6 tcm) and at least 13 giant gas fields (totaling 5.1 tcm).

Most of these fields are either directly owned by Gazprom or by Gazprom joint ventures (with a number of partners).

Gazprom's present biggest hope is Zapolyarnoye gas field in Western Siberia. This highly prolific field should help offset steep declines at the aging Urengoi, Yamburg, Medvzhe, and Orenburg fields.14 For example, the once mighty Urengoi, which produced 200 bcm/year at its peak in the mid-1980s, is now down to 160 bcm/year (with the German company Wintershall AG eyeing potential upstream development there).15 Yet another example is Orenburg field, which produced some 48 bcm/year in the 1980s and has now dwindled to only 24 bcm/year (as half its reserves have been exhausted). In most of the producing Russian gas fields, not only do further declines seem inevitable, but increasing rates of depletion seem possible too.

In order to replace declining output from its currently producing supergiant fields, Gazprom brought Zapolyarnoye field on stream in late 2001 by commissioning its first gas treating plant, with a design capacity of 35 bcm/year. During the first 4 months of 2002, the new field already had produced 10.2 bcm (an average 85 million cu m/day).16 Zapolyarnoye's second and third gas plant, with a design capacity of 32.5 bcm/year each, will be commissioned in 2002 and 2003, respectively. Thus by 2004, Zapolyarnoye should reach its full capacity of 100 bcm/year. Already some 104 wells have been drilled in the field, and another 254 wells are planned.17

Gazprom

Of the 543.4 bcm of gas produced in 2001 by Russia, Gazprom accounted for 88%, or 478.4 bcm. The remaining 66 bcm was produced by independent Russian oil and gas companies: 35 bcm by oil companies, led by OAO Rosneft (5.7 bcm) and OAO Lukoil (3.5 bcm), and the remainder by gas companies, led by Itera Group (21.7 bcm).18

However, there is at present a bottleneck developing with regard to further production increases. The working capacity of Gazprom's trunkline network now stands at 560 bcm/year, so with the present Russian gross production level of 543 bcm/year, that leaves excess capacity of only 16-17 bcm/year.

Not only does Gazprom dominate Russia's gas production, but also its gas reserves, as it holds licenses covering 30.4 tcm of reserves, or 65% of Russia's total gas reserves of 46.9 tcm.

In the area of expertise and technology, Gazprom also leads Russian gas producers, especially with the memorandum of understanding it signed in March 2002 with Schlumberger Ltd. to form a technical alliance for the use of Western production-enhancing technologies in Russian gas fields.19

Other pertinent facts and figures about Gazprom are shown in Table 4.

Now, to manage such a large portfolio of gas fields, trunklines, and industrial facilities spread over the immense Russian expanse is a daunting challenge for any management, even more so for a team of civil servants appointed by politicians.

It is therefore not surprising that Gazprom has had more than its share of problems within its top management. For the past 2 years (since Vladimir Putin's rise to power), a complete management overhaul has occurred at Gazprom. As expressed by the Gazprom director representing the interests of minority shareholders, former Finance Minister Boris Fedorov: "We have begun the enormous task of transforming a company that stood for all the worst of Russia's economy into an international corporation that western investors can increasingly understand."20

The easing of former Gazprom Chairman Rem Vyakhirev into the role of advisor to the present chairman was made gradually. But a spate of 2002 resignations and dismissals within the company must have taken their toll—among them the resignations of First Deputy Chairman Pyotr Rodinov (January 2002) and Deputy Chairman and financial chief Vitaly Savelyev (May 2002),21 as well as the dismissal of Yuri Vyakhirev (Rem's son) from the head of Gazexport, Gazprom's gas export subsidiary.22

And on June 28, 2002, at its annual general meeting, Gazprom's board was consolidated further with the election of Dmitry Medvedev (also deputy head of Russia's Presidential Administration) as its new chairman—thereby providing a useful link between the administration and the company's top management. Gazprom's CEO, Alexei Miller, also was elected to the board for the first time; and both Fedorov and Ruhrgas AG Chairman Burckhard Bergmann were reelected for the third time as independent board members.23

But the reappointment of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC as the company's auditors at the meeting displeased many Gazprom observers. This marked dissatisfaction came to underscore critcism leveled at both Gazprom and its auditors in a February 2002 Business Week article ominously titled, "Gazprom: Russia's Enron?"24

Nevertheless, with its new top management, Gazprom seems on the right track for its "consolidation phase," but not out of the woods yet, although Fedorov opined that "it is getting brighter."

Another sign of improved managerial substance was given in late March 2002 as Gazprom unveiled its strategic priorities. Besides underlining the critical importance of Zapolyarnoye field development, Gazprom highlighted "the comprehensive industrial development of the Yamal Peninsula" as its main strategic goal of the decade.25 This centers on its proposed Yamal-Europe pipeline network, which might well prove of strategic importance for European gas consumers before 2010.

Yamal-Europe pipeline project

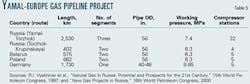

This mammoth project eventually will come to link the supergiant gas fields of the Yamal Peninsula (Bovanenkovsk, Novoportovsk, and Kharassavey) to Kassel, Germany, where it will tie into with the European gas grid. The project's details are given in Table 5. The project's major pipelines eventually will require around 10,900 km of 56-in. pipe designed to the unprecedented operating pressures of 8.3 megapascals.

Of the project's five major sections, only the Belarus and Polish legs have been completed so far (and are being used to carry non-Yamal Russian gas westward). And while building the German section will not pose a big problem, the main 3,000 km Russian route will prove a major challenge, especially its northern portion from Yamal to Ukhta (some 1,220 km), much of which overlies permafrost.

Total investment cost for the Yamal-Europe project is estimated at $45-50 billion.26 The ultimate network design capacity is expected to be 67 bcm/year.

As Zapolyarnoye field development is Gazprom's short-term reply to dwindling production from its aging supergiants in Western Siberia, then the Yamal project is the company's medium-term reply to declines across the board.

But if it really wants to bring the Yamal fields on stream in time, Gazprom will need much more efficient management than in the past. A case in point is the Yamal supergiant gas field Bovanenkovsk, which originally was to have been commissioned in 1997 and is now rescheduled for 2005.

Other major projects

If Gazprom had only Yamal-Europe on its mind, it would prove easier to concentrate on this special megaproject. But Gazprom has a score of other industrial projects on its hands.

First and foremost, there is the almost-completed $2.3 billion Blue Stream pipeline project for exports of Russian gas to Turkey, with a design capacity of 16 bcm/year. The 1,200 km pipeline can be subdivided into three main sections:

- Onshore Russia, ending at Tuapse on the Black Sea (373 km).

- Twin 24-in. subsea pipelines linking Tuapse to Samsun in Turkey (385 km) in record water depths of 2,150 m (requiring a pipe thickness of 31 mm).

- Samsun-Ankara leg onshore Turkey (440 km).

Blue Stream was to have been completed by October 2002 under the original schedule. Gas began flowing through the line at the end of 2002. But the project's main problem now is that the Turkish gas market is not living up to expectations: Turkish gas company Botas had contracted for 25.2 bcm/year of gas, but estimates now are that total demand will reach only 17-20 bcm/year.27

Another major initiative centers on gas export projects to China, South Korea, and Japan—and Gazprom's dream of a "unified system of gas pipelines to the Far East" implemented through its eastern subsidiary Vostokgazprom.28

For covering China's gas import needs, Gazprom is contemplating three major options, with the first option seemingly the most feasible (Table 6). There also is a project for Russian exports through China's Xinjiang autonomous region to Shanghai (>4,200 km), a project that already has attracted the interest of Royal Dutch/Shell Group and ExxonMobil Corp.29 However, a senior Gazprom executive announced at a January 2002 press conference that "the decision on gas shipments to China...would not be finalized before 2010."30

Another Far East project calls for Russian gas exports to South Korea through a 48-56-in., 5,265 km pipeline (4,383 km within Russia) linking the gas fields in the Sakha Republic (Yakutia) to South Korea via Kharabovsk. This pipeline is intended to deliver 34-44 bcm/year and, with some 40 compressor stations, calls for a gross capital investment of $12.5 billion. Gas would come from 10 fields in the Vilyui area (reserves of 0.44 tcm) and 21 fields in the Botuoba area (reserves of 0.58 tcm), in addition to the supergiant Chayanda gas field.31

Along with these Far East projects, Gazprom will be monitoring the development of other gas projects in the area, as these might come to encroach on its potential markets there. Two Sakhalin Island projects under development are possible rivals for Gazprom in Japan and South Korea. The Sakhalin-1 venture has been ongoing since 1975 and now involves joint-venture partners ExxonMobil, India's Oil & Natural Gas Corp., Rosneft, and Sakhalinmornefte- gaz. The project's total investment is earmarked at $12.34 billion (in 2001 dollars), and its first phase (for an 8 bcm/year capacity) was estimated to cost $4.3 billion. So far, some $700 million already has been spent, including drilling that yielded discovery of the three main gas fields: Odoptu, Chaivo, and Arkutun-Dagi (with total gas reserves estimated at 0.5 tcm).32

Sakhalin-2 is a joint venture of Shell with the Japanese firms Mitsui & Co. and Mitsubishi Corp., based upon two main gas fields: Lunskoye and Piltun-Astokhskoye, with total combined reserves of 0.42 tcm. A project investment of $8.5 billion would include an LNG plant (9.6 million tonnes/year) erected at Aniva Bay, on the southern tip of Sakhalin Island, for exports to Japan and South Korea. Awards for contracts on the project's Phase II (including development of Lunskoye) are expected in early 2003.33

Another Gazprom major development on the horizon is that of Shtokmanovsk gas field in the Barents Sea some 500 km from the port of Murmansk. Because of its estimated reserves of 3.3 tcm, it has attracted the attention of six major oil and gas companies: Gazprom subsidiary Rosshelf, Rosneft, ConocoPhillips, TotalFinaElf SA, Norsk Hydro SA, and Fortum Oy. The present understanding is for the Russian partners to put up half the investment and the four foreign companies the other half. The field's development is an extremely expensive enterprise, with its first phase pegged at $15-20 billion and total investment at $40 billion.34

Thus it is not surprising that this project has been idle since 1992, and that the six partners are thinking twice before undertaking such a technically challenging project in an area with such murderous weather.

And Shtokmanovsk is facing legal problems too: on the structure of its production-sharing agreement and especially on the crucial point of downstream pipeline ownership. In any event, Shtokmanovsk was not on Gazprom's budget list for 2002 and will have to wait for its legal, financial, and technical problems to be solved before being given a green light.

In addition, Gazprom will be tackling major exploration work. One area of interest might be the Sakha Republic, where Russian experts predict the discovery of gas fields. For now, Gaz- prom's highest hopes in exploration will be focused on Ob Bay, where Gazprom offshore subsidiary Gazflot drilled two exploratory wells in 2001. Upon the encouraging preliminary results, the Obsky-1 barge (now 80% complete) was to begin drilling operations in Ob Bay at yearend 2002. The company's six Ob Bay blocks are postulated to hold gas reserves of 3-4 tcm.35

Management hurdles

The problems that Gazprom's management will face in the next few years will be commensurate with the immense gas reserves in the company's supergiant fields.

Continuing the retrieval of "stolen assets" while pursuing its "phase of consolidation,"36 Gazprom also will have to accommodate the critical Yamal- Europe project, as well as pay the heavy costs of maintaining its mammoth trunkline network (especially in the permafrost areas37)—all while it implements its exploration and development efforts.

Gazprom still will have to struggle to find the necessary funds to implement its new multibillion-dollar projects while routinely paying interest on its outstanding debt of $9 billion. Low domestic gas tariffs and the timid 15% increase ratified for 2002 will not be helpful. And Gazprom will have to hope for higher gas prices in Western Europe, its main source of income. Even here, the European Union's gas directive has not come to ease its huge problems, but instead has added yet another layer of difficulty for the already beleaguered Russian gas giant.

Thus, there probably will not be enough money available for all of Gazprom's ventures in the next decade, as Deutsche Bank expert Martin Copeland suggested in February 2002,38 calling for more difficult choices on priorities.

Yamal gas destined for Europe undoubtedly will be expensive, and a keen Russian observer wrote that "costly Yamal gas can find its customers only if prices on the world market grow by at least [150-200%] from the [2002] levels [of roughly $3.40/MMbtu] and hold steady at that level for enough time."39 But, on the other hand, the implementation of the Yamal-Europe pipe- line is a necessity both for Gazprom and for Western Europe—probably most vital for Western Europe.

As for some of its JV projects such as Shtokmanovsk, Gazprom will have to await adequate PSA legislation, as current Russian law suffers from "organic incompatibility" with PSAs, and foreign oil and gas companies naturally insist on having a clear-cut deal before getting into a project's execution phase. The PSA might be the last, but possibly not the least, hurdle.

In this respect, the Russian Ministry of Finance has recently "promised to set up a 'closed' list of taxes to be paid by foreign PSA investors" and the Duma (Russia's parliament) continues to debate PSA legislation, hoping to come up with a solution reconciling the intractability of Russian law with the wishes of potential foreign investors (see Point of View beginning on p. 33)

Notwithstanding the legal hurdles on PSAs, Gazprom has begun forging alliances with Western oil and gas operating and service companies for advanced technology and the latest know-how. Such efforts can only multiply in the future as Gazprom reaps the benefits of state-of-the-art technologies, thereby allowing it to maximize production, lower costs, and increase productivity and profits.

The future

The future development of Russia's gas industry greatly will depend on Gazprom, because the company still has a de facto monopoly over gas export pipelines, which doesn't encourage oil and gas companies to develop new gas reserves.40 In fact, Russia's Federal Energy Commission (FEC) makes independent gas companies pay three times as much as Gazprom for transporting gas through the trunkline system, which, although owned and administered by Gazprom, is subject to state control by the FEC.41

In turn, Gazprom's future will come to depend on its top management, now led by CEO Alexei Miller and a new board with Dmitry Medvedev at the helm and directors such as Fedorov and Bergmann. But changes for the better will take time to materialize, and Gazprom has some very serious deadlines to meet. One, among many others, is its commitment to deliver 200 bcm/year to Europe by 2008 under long-term contracts, some of which run through 2025.42

But gas market liberalization and competition engineered by the EU gas directive still might play havoc with Gazprom's traditional long-term, take-or-pay contractual structure, forcing the company to bend backwards to accomodate the new set of liberal rules. However, it could happen that Europe could face a major gas supply shortfall; then, in a typical seller's market, Gaz- prom will be able to dictate its contractual terms to its European customers.

Another major problem Gazprom will have to face soon is the rapid depletion of its aging producing fields. In the report "Russia's Long-Term Energy Strategy to 2020," study coordinator P.P. Bezrukikh proposed that Russia compensate for the supergiants' declines "by increasing the daily yield at gas fields which have entered the final stage of production where output is decliningUand aiming to achieve increases in yields at these wells of 20-30% in 2005, 30-50% in 2010, and 50-100% in 2020."43 To which the reporting journalist could only add: "It would be very interesting to know how such vast increases are to be achieved, but Bezrukikh doesn't tell us."44

Nevertheless, given these postulated yield increases, Bezrukikh predicted that Russian gas output eventually would reach 700 bcm/year in 2010 and 750 bcm/year in 2020 (Fig. 1), thereby almost confirming the forecast of 752.7 bcm/year for 2015 made by N.A. Krylov and V.P. Stupakov of VNIIgaz.

However, it would be surprising if such lofty levels could be reached by then, as any amount over 600 bcm/year would require a 2002-03 revolution in the Russian gas industry.

It should be kept in mind that: 1) gas projects have extremely long lead times (especially in Russia), 2) Gaz- prom has constantly repeated that its main goal is to keep to its production plateau at around 530 bcm/year for the next 2 decades (a very ambitious goal), and 3) non-Gazprom Russian gas producers will face an uphill struggle exceeding their current combined production level of 70 bcm/year.

The author

Ali Morteza Samsam Bakhtiari (www.samsambakhtiari.com) is a senior expert in the corporate planning division of National Iranian Oil Co., Tehran. He specializes in questions related to the global oil, gas, and petrochemical industries, with special emphasis on the Persian Gulf and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Formerly, he lectured on design and economics in the chemical engineering department of Tehran University's Technical Faculty. He holds a PhD in chemical engineering from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology at Zurich.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Miss Behdis Islamnour for assistance provided during the course of research.

References

1. Eastern Bloc Energy, March 2001, p. 19.

2. OGJ, Dec. 24, 2001, p. 127.

3. Energy Information Administration (www.eia.doe.gov).

4. International Gas Report, Mar. 15, 2002, p. 23, and Nefte Kompass, Feb. 14, 2002, p. 6. It should be mentioned that all Russian gas volumes in this article are equivalents at 15° C. (used in most countries) instead of the 20° C. mainly used in Russia; there is a 7% difference between the two.

5. BP Annual Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2002 (www.bp.com).

6. Butler, Malcolm, "Russian Gas for Europe," Oxford Energy Forum, February 2002, p. 4.

7. Ibid., p. 3.

8. Upstream, May 3, 2002, p. 41.

9. O'Sullivan, Stephen, "Gazprom Tariff Disappointment," July 1, 2002 (www.prime-tass.com).

10. Petroleum Economist, April 2002, p. 36.

11. Ibid.

12. Davis, J.D., Blue Gold: the Political Economy of Natural Gas, Allen & Unwin (London), 1984, p. 144.

13. R.I. Vyakhirev et al., "Natural Gas in Russia: Potential and Prospects for the 21st Century' (15th World Petroleum Congress—Forum 10, Beijing, China, 1997); and R.I. Vyakhirev et al., "New Gas Projects in Russia" (16th World Petroleum Congress—Forum 7, Calgary, Canada, 2000).

14. Eastern Bloc Energy, December 2001.

15. "FSU Energy," Petroleum Argus, June 14, 2002, p. 1.

16. Gazprom web site: www.gazprom.ru.

17. "FSU Energy," op cit.

18. International Gas Report, No. 445, Mar. 15, 2002, p. 22.

19. Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, Apr. 8, 2002, p. 7.

20. Fedorov, Boris, "Putin's task," Financial Times, June 18, 2002, p. 15.

21. "FSU Energy," May 31, 2002, p. 11.

22. Ibid. It seems that the young Vyakhirev was ousted to allow Gazprom to regain control of its gas export revenues. The company has since scored successes with both its Hungarian (Panrusgas) and Polish (Gas-Trading) affiliates; moreover, for a revised contract with client Gaz de France, it received an extra $80 million.

23. O'Sullivan, Stephen, "Gazprom AGM report," www.prime-tass.com, July 1, 2002.

24. Starobin, Paul, and Belton, Catherine, "Gazprom: Russia's Enron?", Feb. 18, 2002. The article alleged "shady" deals between Gazprom and Itera Group, as well as Stroitransgaz pipeline construction company (which is 50% owned by people close to former Gazprom directors (e.g., the 6.4% shareholding of Tatyana Dedikova, daughter of R. I. Vyakhirev).

25. Gribanov, Ivan, "Gazprom Sets Forth Strategic Priorities," www.rusenergy.com, Jan. 21, 2002.

26. Petroleum Economist, September 1997, p. VII.

27. FSU Energy, June 7, 2002, p. 5.

28. Petroleum Economist, February 2002, p. 13.

29. Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, July 8, 2002, p. 1. Shell, ExxonMobil, and Gazprom (each with a 15% share) entered into a joint venture with China's PetroChina and Sinopec to develop the 4,200 km West-East gas pipeline project to Shanghai.

30. Gribanov, op cit.

31. Vyakhirev, R. I., 16th WPC, p. 5.

32. Nefte Compass, Mar. 7, 2002, p. 4.

33. FSU Energy, June 14, 2002, p. 4.

34. Nolinsky, Andrey, "Shtokman Project Stymied,"www.rusenergy.com, Jan. 30, 2002.

35. Afanasiev, V., "Russians go for broke in Siberia," Upstream, Apr. 26, 2002, p. 17.

36. Fedorov, op. cit.

37. Butler, op. cit.

38. Copeland, Martin, "'Transporting gas: Capitalizing on the FSU pipeline potential," presentation to the IP Week conference, London, Feb. 19, 2002.

39. Gribanov, op. cit.

40. Upstream, May 3, 2002, p. 41.

41. Eastern Bloc Energy, August 2001, p. 7.

42. Murray, Isabel, "Russia is not short of gas," Oxford Energy Forum, February 2002, pp. 7-8.

43. Eastern Bloc Energy, July 2001, p. 4.

44. Ibid., p. 5.