Middle East crude oil trade: future directions and implications for formula pricing

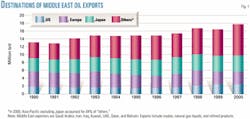

Currently, the total production of crude oil from the Middle East stands at 21.7 million b/d; this is projected to grow to 25.5 million b/d by 2005.

Consequently, the export availability of crude in the region is forecasted to grow from 17 million b/d in 2001 to 19.6 million b/d in 2005.

Furthermore, the region's production capacity is forecasted to increase substantially over the next 4 years, from 23.2 million b/d in 2001 to 26.8 million b/d in 2005.

The Asia-Pacific region is the biggest consumer of Middle Eastern crudes, accounting for almost 60% of the region's exports, followed by Europe (21%) and the US (14%).

The issue of pricing is central to the topic of oil trade. Several pricing mechanisms have been adopted in the past. Currently, Middle Eastern producers use formula-based pricing, which involves the use of different markers and differentials based on the destination.

Formula pricing has led to rather lopsided price levels across various regions, as the Asian consumers pay the so-called "Eastern Premium." At times the crude sold to the US is valued up to $4/bbl less than the same crude going to Asia. In spite of the ensuing criticism, the Eastern Premium might continue to exist. However, in the long run it might become difficult to sustain such premiums as crude markets move towards globalization.

Meanwhile, the search for a credible marker for eastbound sales of Middle Eastern crudes continues. In the absence of a formal trading exchange in the Asia-Pacific market, producers and consumers have relied on Dubai crude as a marker. Recent developments involve the inclusion of the Oman crude in price assessments; this, however, is an interim measure, and several other options are under consideration.

Middle East exports, production

The Middle East1 is the world's center of gravity in the oil market. It is widely known that the region contains the largest oil fields, lowest cost of production, and 66% of world oil reserves.

However, surprisingly, little is understood as to the nature of the exports, nature of the buyers, and direction of the future trade. Moreover, there is still confusion as to how formula pricing will continue to function in the future. This article is an attempt to explain these issues in broad terms.

To complete this report, we have drawn on our database as well as other sources.2 We have tried to avoid using any confidential information but have added our interpretations and insights.

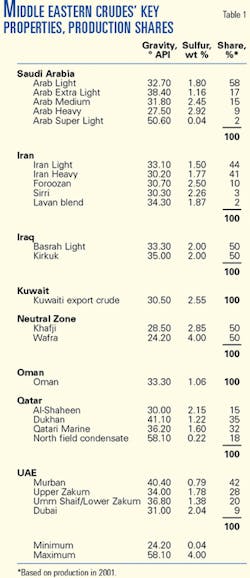

Persian Gulf crudes range from the very light Arab Super Light at over 50° gravity API and 0.04 wt % sulfur to Wafra at 24° gravity API and 4 wt % sulfur. There are also very light condensates with very high sulfur content and quite a few light, medium-sulfur crudes produced in the region (Table 1).

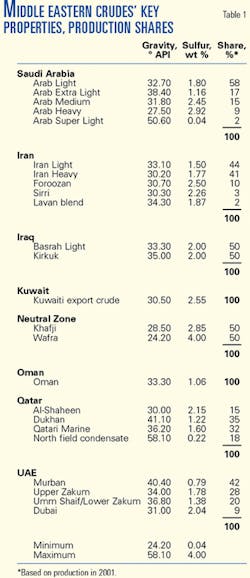

The countries of the Persian Gulf region export oil to almost every corner of the world. Since the late 1980s, exports to Asia have grown substantially. In 2000, almost 60% of the Pesian Gulf exports went to Asia, as compared with 21% to Europe, 14% to the US, 4% to Africa, and 2% to South America.

Within Asia, Japan alone accounted for 40% of all Middle East oil exports to the region in 2000. Japan, South Korea, China, and India are the major importers of Middle East crudes in Asia.

Persian Gulf oil exports were 13 million b/d in 1990; by 2000, they had reached 17.8 million b/d (Fig. 1).

Currently, the production capacity3 of major Middle Eastern oil producers stand at around 23 million b/d. We project substantial increases in this production capacity in the near future. As a high-case scenario, Middle East production capacity might increase by 6 million b/d by 2005 (Table 2). However, it's more likely that that capacity increase may be on the order of 3.6 million b/d by 2005.

Iraq remains a major wild card, and the Kuwaiti government has an ambitious target of attaining 3 million b/d of production capacity (including their share in the Neutral Zone)-which forms the basis of our high-case scenario.

Saudi Arabia

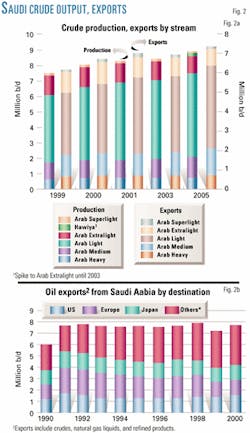

Key oil exporter Saudi Arabia currently has a production capacity of 10 million b/d and produces 8.3 million b/d. We do not foresee a substantial increase in Saudi production capacity, which is most likely to remain at 10-11.5 million b/d by 2005.

Saudi Arabia produces and exports a variety of crudes from very light Arab Super Light to Arab Heavy (Fig. 2). Historically, Arab Light and Arab Heavy were the mainstream of Saudi crudes.

Arab Extra Light was a minor stream that has grown substantially due to the discovery of Shaybah oil field and blending of condensates into the Arab Extra Light stream; it now accounts for 1.3 million b/d.

Arab Super Light's production has declined to 120,000 b/d from 200,000 b/d a few years ago. It is likely to continue to decline slowly to around 100,000 b/d by 2005.

Arab Light is the powerhouse of Saudi crudes, with production of over 5 million b/d and spare capacity too. Arab Heavy and Arab Medium output has been cut back under the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries quota to maximize Arab Extra Light and Arab Light production. Under a quota system, producers are likely to export the highest-priced crudes. Arab Heavy at 700,000 b/d is the minimum production necessary to avoid damaging the source oil field.

Internally, Saudi Arabia consumes no Arab Heavy, no Arab Super Light, and very little Arab Medium. Arab Light is heavily used to run the domestic refineries, together with 200,000-250,000 b/d of Arab Extra Light. Saudi Arabia's oil exports have increased from 6 million b/d in 1990 to 7.6 million b/d in 2000. The kingdom continues its strategic drive to remain the No. 1 crude oil exporter to the US. This is of utmost political importance to Saudi Arabia, and she has succeeded in capturing the top spot (Fig. 2b).

Saudi Arabia has a diversified group of customers. Based on crude term contracts of some 6.5 million b/d in 2001, 38% was sold to Asia-Pacific buyers, 14% to Europe and Africa, and 19% to the Americas. Major integrated oil companies bought 29% of Saudi crudes last year. We do not have the breakdown of where the majors sent the crudes but expect that the vast majority of the crudes ended up with their affiliates in Asia.

Among the top Asia-Pacific crude buyers buying 2.56 million b/d of Saudi crude in 2001, Japan captured the No. 1 spot with 30%, followed by South Korea 27.6%, India 12.5%, China 8.8%, and Pakistan 7.4%.

Iran

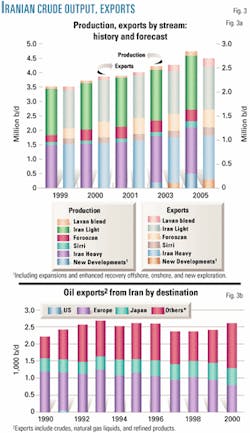

Iran is the second largest oil producer in OPEC and has undertaken policies to attract foreign investment and expand capacity via new projects under buy-back contracts.

In 2001, Iran's estimated production was 3.89 million b/d, just below its production capacity. Our base case projects Iran's capacity to grow 20% by 2005, and the corresponding increase in production is estimated at 22% in the same period (Fig. 3a), whereas exports are projected to grow by 7% by 2005 (Fig. 3b). This corresponds to a forecasted increase in domestic use of the crudes as 90,000 b/d of additional refining capacity is expected to come on line by 2005.

Iran Heavy and Iran Light constitute up to 85% of Iran's total crude production. New streams are likely to come from the buy-back contracts.

The major recipients of Iranian crudes are the European Union and Asia-Pacific. Most of the lighter Lavan blend, the heavier Sirri, and Foroozan blends are sold to customers in the Asia-Pacific region via term contracts. Major customers for Lavan blend are the Indian and Japanese oil companies.

One of the most unusual features of Iranian oil exports are liftings by National Iranian Oil Co. (NIOC) and Naft Iran Co. (NICO)-accounting for 6-7%, or 150,000 b/d of exports in 1999-2000. NICO (a 100% owned unit of NIOC) exports crude oil to nontraditional markets of NIOC, such as the former Soviet republics, Africa, and Latin America. NICO can also buy crude from NIOC at market prices and sells it to others, or it hedges in the futures market and uses the crude in its own arms-length commercial transactions.

Iraq

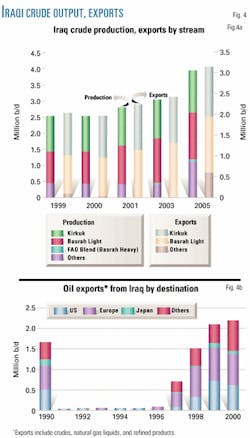

Iraq has the world's second largest proven oil reserves, which could last over 100 years at the current level of production. This number increases radically if probable and possible reserves are added.

Iraq's current production capacity stands at 3.1 million b/d, which is close to its current level of production 2.8 million b/d.

Iraq's production capacity could be anywhere from 3.0 million b/d to 4.5 million b/d by 2005. This depends on several factors; most important are the extent of international oil company (IOC) involvement and spending on maintenance in Iraq's upstream sector.

Iraq needs to make much-awaited investment to revamp and maintain its debilitated oil infrastructure. A positive move in this direction was last year's decision by the UN to allow doubling of the spending limit for Iraq's oil sector.

Iraq's production and exports are projected to increase by almost 40% during 2001-05 (Fig. 4a).

Iraq produces two major streams: Kirkuk and Basrah Light from its Kirkuk and Rumaila fields, respectively. In recent years Basrah blend has become heavier due to the addition of 29-30° gravity API volumes. The blend is now rated at 32-33° gravity vs. 34° gravity earlier. Kirkuk is relatively lighter. However, like Basrah Light, its quality has also deteriorated with the mixing of fuel oil and naphtha.

After the 1990-91 Persian Gulf crisis, Iraq resumed its exports under the UN oil-for-aid program introduced in 1995. Its exports have been increasing steadily since 1997. Most of Iraq's oil heads westward (Fig. 4b).

Kirkuk is exported from the port of Ceyhan through Turkey via the Iraq-Turkey pipeline, and therefore finds most of its markets in the Atlantic Basin. Basrah's main destinations are the Asia-Pacific region and the US. In 2000 Europe and the US accounted for almost 70% of Iraqi crude sales, with Asia netting 19%.

UAE

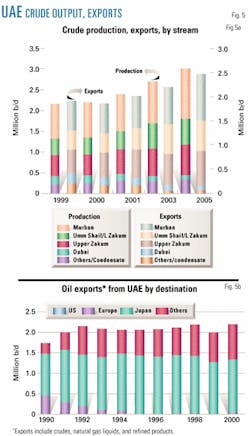

UAE is a federation of seven emirates,with Abu Dhabi holding almost 95% of proven oil reserves, followed by Dubai, Sharjah and others.

On the whole, UAE's current level of production, 2.4 million b/d, is close to its capacity. We forecast an increase of 20% in UAE's production capacity by 2005. Correspondingly, UAE production is projected to increase by almost 15% in the same period of time (Fig. 5a).

Abu Dhabi's major export blends include Murban, which accounts for 40% of total crude exports from the emirates. This blend enjoys a premium for its light weight and relatively low sulfur content. With a relatively higher yield of middle distillates, it is mainly marketed in the Asia-Pacific region, with term contract buyers in Japan (Fig. 5b).

Besides Murban, Lower and Upper Zakum crudes are also marketed mainly eastward. Lower Zakum is sold almost exclusively to Japan; other customers include South Korea and Singapore. And Upper Zakum is sold to Japanese, Singaporean, and South Korean refiners. Most of Abu Dhabi's crude therefore heads eastward, with Japan accounting for almost 60% in recent years.

Dubai crude has recently been the center of attention, as it is the price marker for Middle Eastern crudes sold in the Asia-Pacific region. In recent years its output has been declining, from almost 400,000 b/d in 1990 to 170,000 b/d in 2000. It is projected to decline further to some 100,000 b/d in the medium term. With decreasing trade volume, Dubai has come under increased criticism from importers, as a relatively small number of traders can manipulate its price and affect the selling price of all the Middle Eastern crudes to the Asia-Pacific region. Therefore, there is increasing pressure to adapt a more widely traded and therefore a more transparent marker for the eastbound Middle Eastern crudes.

Kuwait

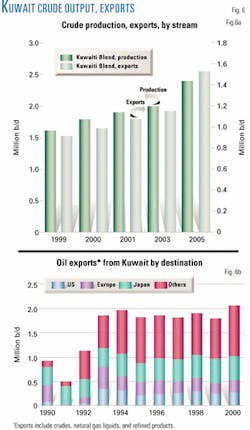

Kuwait holds a little under one tenth of world oil reserves, and at current rates of production, its reserves will last over 100 years.

Kuwait is one of the countries in the region with significant excess production capacity, currently 10%. The current production capacity of 2.125 million b/d is projected to grow by 25% by 2005. If the Kuwaiti government makes the groundbreaking decision to allow the involvement of IOCs in its upstream oil sector, Kuwait's production capacity may exceed 3 million b/d by 2005.

The production of Kuwaiti Export Crude (KEC) blend is projected to increase by 26% from the current level to 2005 (Fig. 6a). And with no significant projected additions in Kuwait's refining capacity, the export availability is projected to increase by 42% in the same period.

Kuwaiti oil fields hold medium to heavy gravity crudes at 30-36° gravity. KEC is a mix of crudes from these fields and the more sour crudes from the Neutral Zone, which include Khafji and Wafra. The final export blend is 30.5° gravity with 2.55 wt % sulfur.

Most of Kuwait's oil heads eastward, with the US and the EU together accounting for a fourth of Kuwaiti oil exports. In 2000, Japan accounted for 24% of Kuwait's oil exports. Besides Japan, refiners in India, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand also import Kuwaiti oil.

Oman

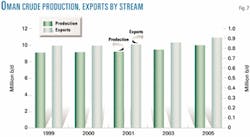

Oman's oil production is projected to grow by 7% by 2005 from a current level of 965,000 b/d (Fig. 7). Production from several Omani fields is combined into a single stream with API gravity of 33.3° and 1.06 wt % sulfur-slightly better than the average Middle Eastern crude.

With a low level of domestic consumption, Oman exports most of its production, volumes of which are projected to grow by 8% by 2005.

Oman's crude production increased by less than 1% in 2000, falling short of the targeted production of 850,000 b/d, primarily due to the continued decline in Yibal field's output.

About 50% of Oman's oil is sold via term contracts. And most of it heads eastward, with occasional cargoes marketed to the Atlantic Basin and US West Coast. The major importers of Omani crude in the Asia-Pacific region are Japan, Thailand, South Korea, and China. China in 2000 accounted for than one third of Omani oil purchases.

Omani crude is considered a serious candidate to replace Dubai as the marker for Middle Eastern crudes sold to the Asia-Pacific countries.

The argument in favor of that is that Dubai's decreasing production and trade volumes are more susceptible to manipulation and therefore an alternative marker; for example, Oman, with export volumes of 800,000-900,000 b/d, should replace it. However, a counterargument exists that reasons that Royal Dutch/Shell's 34% interest in Petroleum Development Oman Ltd. could lead to a situation where a single producer could have a major influence on prices.

Qatar

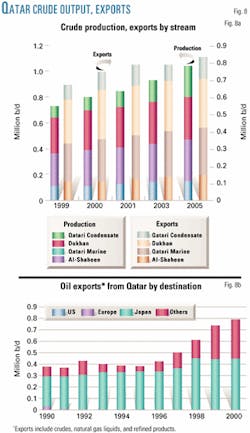

Qatar is currently producing close to its capacity of 850,000 b/d. Qatar produces four major blends: Dukhan, Qatari Marine, Qatari condensate, and Al-Shaheen. These streams are spread over a gravity range of 30-58° API.

On the whole, Qatar's oil production is projected to increase by 23% by 2005, and exports by 12% (Fig. 8).

Qatari condensate production is projected to double by 2005 from the 2001 level; however an expected addition of almost 200,000 b/d in Qatar's condensate splitter capacity will result in significant volumes being consumed domestically.

Dukhan and Marine will remain major Qatari export blends; however, Al-Shaheen crude output has increased considerably in recent years. It is expected that the crude will play a more significant role in Qatar's future export mix.

Most of Qatar's exports head for the Asia-Pacific region, particularly Japan, which accounted for almost 56% of the total exports in 2000 (Fig. 8b). Al-Shaheen, for example, is sold to refiners in Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. Dukhan, with its good yield for light products, is sold mainly to Asian customers. Similarly, Qatari Marine has traditionally been purchased by Japan via term deals.

Crude price mechanism

The issue of pricing mechanisms is central to the topic of Middle East crude trade.

Before 1986, Arab Light crude (ALC) was used as an OPEC marker for sales of Middle Eastern crudes worldwide. There were no destination controls, and every nation priced its crude off ALC.

However, the mechanism was abused, as it allowed some of the exporters to undercut the marker-i.e., sell their oil below the marker and grab Saudi market share. It was not long before ALC was dropped as the marker.

In the late 1980s, price formulas were adopted to set export prices. This involved use of three indices for sales of Middle Eastern crudes to various regions: West Texas Intermediate for sales to the US, Brent for sales to Europe, and a combination of Dubai and Oman for sales to the Asia-Pacific region.

In general, a marker crude should fulfill certain implicit criteria in that it should be:

- A good representative of all the alternative crudes available to buyers in the region in terms of gravity and sulfur content.

- Produced in significant volumes.

- Liquid, i.e., significantly traded in the physical market.

WTI is not traded internationally; however, it is significant because it is the main grade used as the benchmark for light, sweet crude futures contract on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX). Brent, on the other hand, is recognized as an international benchmark, with well-established spot, forward, and futures markets. WTI and Brent futures markets (including options markets) amount to 200-300 million b/d of paper trade in comparison to some 1.5 million b/d of physical trade in those two crudes.

The Asia-Pacific market is unique in the sense that it lacks a formal exchange where buyers and sellers meet, and the price thus determined is a realistic determinant of the underlying economic forces. Furthermore, there is a lack of formal trade in paper barrels, particularly a futures market (although there is a forward market) which translates into low transparency for price determination. Because of this, Middle Eastern producers currently rely upon Middle Eastern crudes-Dubai and Oman-as a marker for their eastbound sales. Under the present system, Dubai impacts Oman, and as such, the role of Oman is very minor.

The selling price is based on the price of the marker plus or minus a differential:

Pexport crude = Pmarker crude ± Differential

Where, Pexport crude is the price of export crude, e.g., ALC, and Pmarker crude is the spot price of marker crude, e.g., Brent or a combination of Dubai and Oman.

Perhaps the most important component of the formula is the differential, which is set and announced by oil producers in the Middle East. This is usually set by Saudi Arabia and is closely followed by other Middle Eastern exporters. The differential can be either negative, in the case of discounted pricing, or positive, in the case of a premium. Theoretically, the differential should reflect the difference between the Gross Product Worth (GPW) of the marker and export crude and the difference in the freight cost from the point of origin to the point of comparison for the two crudes:

Differential =

(GPW marker - GPW export) +

(FC export - FC marker) where FC is the freight cost.

In practical terms, the formulas and therefore the differentials are set ahead of the actual time of transaction. This implies that the formula might not reflect the "true" selling price at the time of delivery. The idea can be further explored by observing the differences between calculated and lagged actual differentials over a period of time. One can therefore test the hypothesis if the differentials are set based on economic factors, e.g., GPW and freight cost, or involve some other considerations as well.

One might criticize the formula pricing system, as it has limitations in reflecting the true value of the crude as captured by a netback pricing mechanism. However, such a system might not be practically viable. It was tried for a short period of time just before the introduction of formula pricing. The netback pricing mechanism is based on the idea that the netback value (N = GPW - freight cost - variable refining costs) should be reflected in the selling price of the crude. The system was taken up at the end of 1985; however, it failed as it ran into practical difficulties. It was soon realized that getting a consensus on crude yields, refining costs, freight costs, and profit margins between buyer and seller is not so straightforward.

More importantly, the netback system led to a sharp decline in oil prices in 1986, because it provided the incentive for refiners to maximize crude runs and drive product prices down, which in turn reduces the netback value of crude. The system was therefore abandoned and was replaced by price formulas.

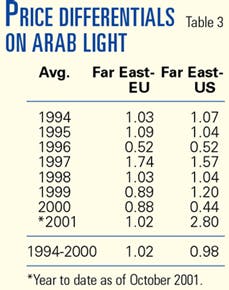

The use of destination-based price formulas lead to a rather disjointed system of pricing for the Middle Eastern crudes. This essentially means the same crude is priced differently depending on its destination (on an FOB basis). Asian customers have traditionally been at a disadvantage, as eastbound sales are usually at a premium to the marker crude, and sales to Europe and the US are at a discount to their markers (Fig. 9). These differentials are calculated on the basis of ALC sales to the US, Europe, and Asia-Pacific, and the selling price is calculated using differentials announced by Saudi Aramco each month.

It is evident from the differentials for Far East-US and Far East-Europe that eastbound sales are generally at a premium vs. sales to the US and Europe. This Eastern Premium has fluctuated at $2-5/bbl in recent years. One can argue that the Asia-Europe spread seems to be stabilizing or declining in the last 4 years; however, it's not certain if this is a sustainable trend (Table 3).

Supporting the premiums is the reason that the term contracts disallow the reselling of the crude and therefore exclude the possibility of profiting from these differentiated prices, which would force the same crude to be sold at the same FOB price, irrespective of the destination.

Dubai marker validity

Currently, the validity of Dubai as a marker is being questioned as the crude's production volume has fallen, as noted earlier. This is further compounded by the fact that Dubai itself does not stand as an independent marker. This is so because, starting in the late 1980s, there was a move towards spread trading rather than outright deals-spread between Dubai and the 15-day forward Brent market, which now accounts for almost 95% of the transactions, implying that Dubai is more of a derived indicator rather than an independent one.

There were several reasons why Dubai was chosen as a marker for eastbound sales. First, the production of Dubai crude was well diversified-divided at the time among Conoco Inc. 30%, Total SA 25%, Respol SA 25%, and others. It was therefore assumed to be less susceptible to manipulation by a single player. Furthermore, Dubai was (and still is) the only actively traded crude in spot and forward markets that is representative of the generally high-sulfur and medium-to-low-gravity Middle Eastern crudes destined for eastbound sales. Furthermore, initially as many as 25 cargoes of Dubai were traded each month. Dubai trade has now fallen to less than 12 cargoes/month.

In a nutshell, the current Middle East crude pricing mechanism-particularly that for eastbound sales-is not a good representative of the economic forces and therefore cannot be sustained for long. Several factors are likely to facilitate the move away from the status quo. For example, an increasing need to cut costs by the Asian refiners would result in the need for more-competitive deals.

Furthermore, the increasing trend of imports of Atlantic Basin crudes (which are priced off Brent) into Asia-Pacific countries may further pressure Middle Eastern producers to reduce, if not remove, the Eastern Premium. In 2000, over 900,000 b/d of Atlantic Basin crudes were exported to the Asia-Pacific region, up from just over 500,000 b/d in 1996. It is therefore quite possible that the Eastern Premiums on Middle Eastern crude will shrink in the future.

Another potential development would be the creation of a futures market as increased transactions on paper barrels will improve the mechanism of price determination.

New formulas sought

While the buyers of Middle East crudes complain about Dubai volatility due to low physical volume or manipulation, the exporters themselves are not too pleased with Dubai either. They prefer transparency and stability to confusion or volatility.

Indeed, it is exactly for these reasons that Saudi Aramco decided to move away from using dated Brent for its European sales and adopted the Brent weighted average (Bwave) starting Apr. 1, 2001, followed by Kuwait and Iran. Bwave is published by London's International Petroleum Exchange. It is based on the weighted average by volumes of futures contracts on Brent and said to be more stable than dated Brent (Fig. 10).

In continuation of their pursuit for a stable pricing system, OPEC adopted a price band mechanism. This mechanism, introduced in first quarter 2000, involves administration of prices (the OPEC basket of crudes) within $22-28/bbl. A breach of the band would result in automatic production adjustment-prices exceeding the upper bound for 20 consecutive days would result in a production increase of 500,000 b/d, and prices dropping below the lower bound for 10 consecutive days would result in a production decrease of 500,000 b/d.

The serious limitations of this system have been exposed in the recent events-where the largest price decline in a single day over the last decade was experienced following the terrorist attacks on the US, and OPEC, until recently, refrained from exercising the "automatic" production adjustment, given the political scenario and deteriorating economic growth. The effectiveness of this price band mechanism is now being questioned, increasingly warranting fundamental changes in the mechanism.

Meanwhile, Platts Pricing Service, which reports crude and product prices in the Asia-Pacific market, has prepared a new pricing system. Announcing that as of Nov. 16, 2001, the Dubai crude oil assessment was to be redefined.

From this date it was to start expiring its Dubai assessments 2 weeks earlier, allowing the sellers to deliver Oman into Dubai bids-which will have to be declared at the time of execution. The objective of the early expiration is to harmonize the trading period of Dubai with other Middle Eastern crudes.

The industry has some reservations, but everyone, including the key Middle East exporters, is willing to go along with Platts at least as an interim measure. After a while, exporters and importers will assess whether the Platts proposal is acceptable to them, and the Omani government will decide if it is willing to have Omani crude as a marker. Oman says it is willing to consider the option but so far has moved very cautiously. After all, it is not exactly clear what the advantage is for Oman, beyond possibly only prestige. Even then, Oman may create liquidity to become a marker on its own or 50-50 with Dubai.

Sometime early this year, the fate of the marker for the East will become clearer. Oman is not the only option being considered as the marker. Other proposals suggest the use of WTI or Brent and weighing in volumes from Al-Shaheen, Arab Medium, and Upper Zakum besides Oman.

Eastern Premium's fate

One thing, however is still certain: The Eastern Premium of around $1/bbl is likely to be paid by Eastern buyers under any formula, whether Dubai or Oman, at least for the next year or two. What may change is the volatility of the marker caused by price manipulation, not the premium itself.

Finally, the question is often asked: Is there any justification for an Eastern Premium at all? The answer depends on the different viewpoints. The Asians' point of view considers the premium unfair and unreasonable. It argues that higher Eastern prices at a time of devastating refining margins are intolerable. Moreover, the Asians consider European exports from the Mediterranean (particularly gas oil) competing with their products based on the cheaper Middle Eastern crude. As such, they see themselves squeezed unfairly.

The Middle East exporters see things differently. They see the Eastern premium as nothing but market reality. The Asians have no better alternatives than the Middle Eastern crudes. Atlantic Basin imports provide only limited competition, because Asian refineries are designed for Middle East crudes. If Asians had any real alternatives, they would have already switched. They have no choice but to pay the Eastern Premium.

In a way, both sides are right: Asians are suffering because of low refining margins, but they do not have much of a choice. In the long term, we cannot have a globalized product market at the same time as a regionalized crude market. With product markets moving to become globalized by 2005 as a result of harmonization of specifications, crude prices must also become globalized. It is theoretically difficult to justify the continuation of the Eastern Premium beyond 2005 or even earlier. For the time being, the Eastern Premium is alive and well and is going to be paid.

Future directions

Middle East crude promises to continue domination of the global oil market for many years to come. There is virtually no scenario in which the role of Middle Eastern crudes will diminish, despite the addition in crude oil output from Central Asia and Africa.

Where will the Middle Eastern crudes flow? The natural home of Middle East crude is in Asia. That large volume of Saudi and Iraqi crudes are exported to the US is due to specific policy imperatives rather than economics. Crude oil exported to the US has been valued at times up to $4/bbl lower than the same crude going to Asia. The so-called Eastern Premium is around $1/bbl crude going to Europe vs. Asia. The direction of exports are heavily influenced by politics and regulation.

Destination controls and formula pricing are unnatural behavior in the global oil market. Still, they have been in existence for many years and may well continue for several more years, but their time is running out.

Sooner or later, a Middle East crude or a basket will emerge as a marker. Then flows will be determined by economic factors, and exports to the West become balancing in nature. Middle East crudes will slowly tend to focus on their natural home: the Asian market.

References

- Middle East refers to Persian Gulf countries. For purposes of this article, Middle East and Persian Gulf are used interchangeably.

- We have used the following sources in addition to our own databases: Middle East Economic Survey, Petroleum Argus, BP Statistical Review, International Energy Agency, and US Energy Information Administration data and reports.

- Please refer to FACTS Energy Advisory #251, OPEC Production Capacity Trends: A Quiet Revolution, for further discussion on production capacity of Middle Eastern OPEC members and its relation with crude prices.

The authors

Hassaan S. Vahidy holds an MA in economics from the University of Hawaii at Manoa and an MBA and a BS in engineering. He is currently a senior associate at FACTS Inc. and a researcher at the East-West Center in Honolulu, involved in downstream oil and gas research for the Asia-Pacific and Middle East regions. Prior to this position, Vahidy worked for Royal Dutch/Shell in Pakistan.

Fereidun Fesharaki is president and founder of FACTS Inc. He also is a senior fellow at the East-West Center, Honolulu. Fesharaki received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey, England. He then completed a visiting fellowship at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern Studies. In the late 1970s, he attended the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' ministerial conferences as energy adviser to the prime minister of Iran.