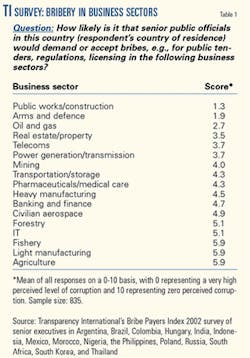

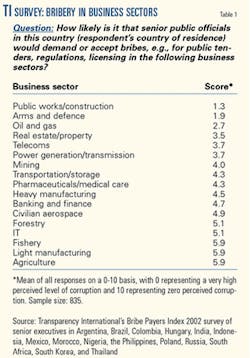

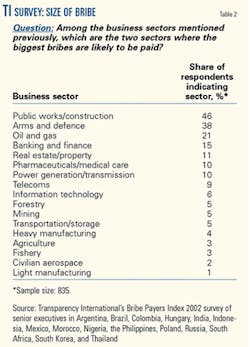

Problems of corruption in the oil and gas sector of the business world stood out in a recent survey commissioned by Transparency International (TI), a nongovernmental organization (NGO). In research conducted for TI's 2002 Bribe Payers' Index (BPI), business people in 15 emerging markets assessed 17 commercial sectors for their propensity to corruption.1 They were asked to identify the sectors where officials were most likely to demand bribes, as well as the sectors where the biggest bribes were actually paid. In response to both questions, the polling sample cited construction and defense as the industries most prone to corruption. Oil and gas came in third.

The BPI is a survey of opinions and perceptions rather than an objective measure. But perceptions matter. If international petroleum companies are seen as corrupt, they risk losing their welcome in countries offering upstream opportunities. Downstream, they run a greater risk of consumer boycotts, legal action, and angry questions at shareholders' meetings. The reputational issues associated with corruption matter to the industry as a whole, not just to individual companies.

The good news is that the international community is making solid progress in its efforts to check corruption. In particular, the major industrialized countries have reached consensus on the legal instruments needed to curb transnational commercial bribery. The bad news is that progress is uneven. Implementation of anticorruption laws remains inconsistent, and companies still fear that they will lose out to corrupt competitors if they refuse to pay bribes.

This article reviews progress in the struggle against transnational corruption. It argues that recent legal reforms are an important but insufficient remedy. There is much more that companies can do to support the campaign against corruption, both individually and collectively.

Defining the problem

The standard working definition of corruption has been "the abuse of public position for private gain," referring to bribery involving officials in their dealings with companies and individuals. This definition certainly should be extended to include private-private bribery: for example, kickbacks paid by suppliers or subcontractors to secure orders. Money-laundering and accounting fraud are related to the wider problems of corporate integrity but lie outside the scope of this article, which focuses on three core issues:

- Bribery to secure business advantage in the form of licenses or contracts. In the petroleum sector, such bribes can easily run into millions of dollars. They are damaging because they raise costs and reduce the revenue available to the host country. Companies that pay risk reputational damage in their home countries, and they are almost certain to face repeat demands.

- "Facilitating" or "facilitation" payments, otherwise known as "speed money." In many countries it is common to pay officials small amounts of money to accelerate routine transactions such as customs clearances or telephone connections. At first sight such payments seem less damaging than the grand corruption involved in multimillion-dollar bribes. However, if facilitating payments are pervasive, they can have a corrosive impact on society as a whole. As will be seen, the role of international companies in this area is becoming more controversial.

- Government transparency. In countries such as Nigeria and Angola, official accounting for the revenue derived from oil and gas is either incomplete or obscure. Much of the revenue is thought to end up in the private bank accounts of well-placed individuals; no more than a limited amount is spent on social development, even in-or especially in-oil-producing regions. Companies are not responsible for government accounts or spending decisions, but malpractice in these areas affects the reputation of the entire industry. So what can companies or other international actors do to improve the situation?

All three varieties of corruption touch on the question of power. How much influence do petroleum companies have in the countries where they operate? And how should they exercise it?

No one actively defends corruption, but executives frequently argue that as outsiders they have limited influence on practices that are considered routine in their host countries. And if they refuse to pay, or embarrass their government counterparts, their companies will lose out to unscrupulous competitors.

Oil's high rank

There are several reasons why the petroleum sector ranks so high in TI's index.

The first is its sheer size. In many countries, oil and gas account for 50% of the national economy or even more. In Equatorial Guinea the economy grew by 70% in 2001 entirely because of petroleum. It is scarcely surprising if officials in countries with poor records of governance seek an opportunity to take their share.

The second reason follows from the first. The industry's size and strategic importance mean that it typically is closely regulated. Individual officials enjoy a high degree of discretion in their interpretation of regulations, and are therefore well placed to seek extra payment for reaching the "right" decision. The commercial emphasis on rapid results enhances the officials' negotiating position. If executives are under pressure, they are less likely to haggle.

The third issue is a matter of political geography. Famously, petroleum companies have to go where the geology takes them, and the most exciting new reserves are mostly in regions that present great technical or political challenges. However, geography alone is not sufficient to explain what has become known as the "curse of oil"-the apparent link between oil reserves and corrupt or oppressive re- gimes. Recent studies argue that petroleum and other natural resources tend to distort political economies.2 3 Oil becomes a curse where it reinforces the power of pre- datory regimes by giving them an easy source of revenue without the need to seek authority or support from their citizens.

Legal initiatives

Legal reform is part-but only part-of the answer to corruption. It is not the whole answer because the existence of laws makes little difference unless they are actively enforced, and in this respect the international record has been patchy. The emergence of new laws governing transnational bribery is a positive step, but the key issue is implementation.

Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

To its credit, the US has taken the lead in legal initiatives to combat international corruption. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), in force since 1977, makes it possible for the US authorities to prosecute US companies for paying bribes anywhere in the world.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) have actively enforced the law. The total number of prosecutions is relatively low-about 40 in the case of the DOJ-but the act makes a difference. No major US company wishes to risk the public humiliation of being taken to court in a corruption case. As a result, all major US-based international companies have introduced FCPA compliance programs to make sure that key executives are aware of the implications of the law.

International conventions

US companies have long complained that the FCPA puts them at a disadvantage when faced by unscrupulous competitors that do not face the same legal restrictions.

This concern has been partially addressed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) convention on bribery in transnational business transactions, which was signed in 1997 and came into force in 1999 (see www.oecd.org). Under the terms of the convention, the OECD's 35 member countries have undertaken to introduce laws similar to the FCPA that make it possible to prosecute companies that pay bribes abroad. All these new laws are now in place and, at least in principle, this means that competing companies from the major industrialized countries are playing by the same rules.

In practice, the impact of the convention has so far been limited. Governments may have introduced laws, but they have been slow to publicize them, and, outside specialist legal circles, there is limited public awareness of the full implications.

Crucially, there have so far been no prosecutions that are directly attributable to the convention. In part this may be because of a lack of resources: As the DOJ well knows, it takes considerable time and expense to prosecute a corruption offense that took place abroad. The lack of prosecutions may also reflect limited political will.

US experience suggests that it will take no more than a handful of successful prosecutions to raise public awareness of the new OECD anticorruption laws dramatically. But this needs to happen soon.

Meanwhile, there are several other international initiatives against corruption. The most important include an agreement signed by the Organization of American States (OAS) similar to the OECD convention. The Council of Europe has set up a monitoring body, the Group of States Against Corruption (known, after its French acronym, as GRECO), which assesses the 40 member states' compliance with the council's anticorruption instruments. And the UN General Assembly has passed a resolution calling for a future UN Convention against Corruption.

These initiatives together constitute an important sign of the times. They establish a clear set of markers demonstrating that commercial bribery is no longer seen as acceptable. But the task of resolving the problem falls as much to companies as to governments.

Anticorruption policies

With companies, as with governments, the key question is no longer policy, but implementation.

Nobody now seriously defends bribery as an acceptable means of promoting international business, but there is considerable public scepticism about companies' willingness to implement their declared anticorruption principles. This scepticism will be all the greater following the collapse of Enron Corp. and other corporate scandals in 2001 and 2002.

So what are the ingredients of success?

Corporate culture

The first requirement is a clear sense of direction from the top.

In the UK, BP Chief Executive John Browne and Mark Moody-Stuart, the former group managing director of Royal Dutch/Shell Group, have been particularly outspoken in their condemnation of commercial corruption.

Secondly, it is not sufficient simply to publish a code of conduct. The contents need to be communicated to suppliers and business partners as well as company employees, and they should be translated into the appropriate languages. In China, US companies have distributed Chinese translations of the FCPA so that their local counterparts know what to expect.

Third, there need to be clear reporting lines so that employees know what to do and whom to consult when a problem arises. This includes the provision of different channels of communication for employees who suspect some infringement of the company's ethical code: Some may prefer to talk to a company ombudsman; others may prefer e-mail or anonymous telephone hotlines.

All these measures need to be set in a corporate culture where employees know that they will be rewarded for integrity and not simply for achieving financial targets by whatever aggressive means possible. As the Financial Times argues in its analysis of the Enron collapse, "The main factor that discouraged questioning of Enron's business practices was a ruthless and reckless corporate culture that lavished rewards on those who played the game, while persecuting those who raised objections."4

Facilitating payments

Almost all company codes of conduct now explicitly forbid employees to pay bribes to secure business. However, they differ in their policy on small "grease payments" or "speed money."

The FCPA specifically excludes "facilitating payments" from its definition of bribery. It defines these as payments to speed up "routine governmental action" such as processing visas or work permits and providing a phone service or power or water supplies. It is understood that facilitating payments are relatively small although the FCPA does not specify any limit.

Such payments are considered routine in many developing countries, and the decision to exclude them from the FCPA could be considered a pragmatic response to an unfortunate social reality. Many US and other international companies have allowed employees to pay provided that the payments are genuinely customary; the amounts paid are properly recorded; and there is no realistic alternative. However, this approach creates both practical and legal problems.

First, it is often difficult to define the distinction between a "facilitating payment" and a "bribe." If a company gains a reputation for willingness to make small payments, it will find it harder to resist demands for more substantial bribes. Secondly, such payments are rarely legal in the country concerned, even where they are customary. If a company condones facilitating payments as part of its official policy, it appears to be sanctioning a deliberate breach of the local law.

The main text of the OECD convention does not specifically refer to grease payments although the official commentary says small facilitation payments do not come within its definition of bribes paid to "obtain or retain business." The texts of the laws passed by individual OECD member countries differ on this point. For example, the new UK law on transnational corruption, which came into effect in February, makes no distinction between different forms of payment. Since then, BP has specifically forbidden facilitation payments, and this ruling applies to all its operations worldwide-including those based in the US.

The policy of banning facilitating payments outright makes good legal sense. However, companies will need to ensure that they give their employees full support when putting it into practice, particularly when introducing a stricter new policy after an earlier period of laxity. Senior management must ensure that the new company policy is well publicized; they may need to accept longer bureaucratic delays; and they will need to recognize that some payments genuinely amount to a form of extortion. When confronted with an armed, drunken militiaman demanding a spurious traffic fine, you may have little choice: You pay.

Intermediaries

A second controversial area is the role of intermediaries or third parties-whether agents, joint venture partners, or consultants.

Companies routinely employ commercial agents to help them win business, particularly in unfamiliar jurisdictions. Such agents may be paid by commission, and in the past many business people have argued that it is no concern of theirs if part of the commission is passed on as a bribe to some company official.

Similarly, foreign companies operating in the former Soviet Union often expect their joint venture partners to act as a buffer from dubious local business practices: Local partners know what needs to be done and how. It is best to let them get on with it.

Such attitudes are misguided for both practical and legal reasons. The FCPA is particularly clear on this point. According to the act's "knowledge principle," companies do not need to have definite information that a bribe has been paid on their behalf; they can be prosecuted if they might reasonably have suspected that an agent might pay a bribe on their behalf.

In 1997 Triton Energy Ltd., Dallas, fell afoul of the FCPA when it faced US Securities and Exchange Commission civil action on account of its activities in Indonesia. Triton and two former officers of its Indonesian subsidiary were accused of authorizing "numerous improper payments" to Roland Siouffi, a business agent. The SEC charged Triton with "knowing or recklessly disregarding the high probability that Siouffi either had or would pass such payments along to Indonesian government employees." Triton agreed to pay a $300,000 penalty without admitting or denying the charges.

More recently, in 2001 Baker Hughes Inc., Houston, the oil services company, reached a settlement with the DOJ and the SEC on another Indonesian case. PT Eastman Christiansen (PTEC), an Indonesian company controlled by Baker Hughes, had paid a fee to an Indonesian affiliate of KPMG. The accountants in turn had passed on part of the fee to a tax official in the hope of securing a reduction in Baker Hughes' tax bill.

This transaction took place against the advice of Baker Hughes's general counsel, who reported it to the US authorities. As a result of Baker Hughes's corrective action, the authorities imposed no fine on the company, but there was never any suggestion that the fact that the payment had been made via an intermediary amounted to any kind of defense.

Corrupt environments

Codes of practice backed by senior management are an important part of companies' armory against corruption. If they can establish that they simply do not pay, they are less likely to receive demands in the first place. However, they still face the challenge of winning business honestly in environments where corruption is commonplace.

To succeed, companies need to develop a high degree of diplomatic skill. They need to identify key figures and potential hazards well in advance: Who really makes the decisions, and what motivates them? What are their interests? Are they motivated primarily by the desire for financial gain? Or do they have other concerns-for example, a political requirement to promote development in a particular part of the country?

Many of the "alternatives" to bribery raise problems of their own. For example, it is no use contributing to charity as a goodwill gesture if the charity lacks transparency and happens to be controlled by the president's wife.

Expenses-paid visits to Europe or the US are sometimes seen as another alternative means of influencing decision-makers. There may be legitimate reasons for officials to make such trips-for example, to see a working example of a proposed petroleum facility-but the practice is open to abuse if it is seen simply as a perquisite or if the officials' wives accompany them.

At the most practical level, if companies dispense such perks freely, they will create further demand. They may also face legal problems. In 1999 the DOJ prosecuted Metcalfe & Eddy Inc. for financing an Egyptian official's visits to the US, together with his wife and two children. The DOJ argued that the company paid their expenses as a means of securing a business advantage.

Collective initiatives

Companies arguably make their most important contributions to society where they espouse and implement strong standards of corporate integrity and make sure that their business partners do the same. However, individual companies acting on their own will have no more than a limited impact on the wider problems of corruption.

Effective reform requires a collaborative approach involving different groups of companies and companies working in association with civil society and government.

Industry associations

Collective industry initiatives against corruption make sense for two main reasons.

First, it is easier to establish a "level playing field" if all major companies in the petroleum sector-in this case-are committed to the same rules.

Secondly, a major scandal involving a single company will weaken the reputation of the sector as a whole. It is in the industry's collective interests to make sure that this does not happen.

The oil and gas sector is still at an early stage in building up a common front against corruption. The International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (OGP) has established industry guidelines on issues such as environmental management and in November 2001 held an initial meeting in Houston to discuss the corruption issue. Among the ideas discussed were proposals to share best practice in due diligence and training, both within the OGP and-ideally-with other related industry associations.

In this as in other issues, one of the OGP's greatest challenges will be to achieve consensus among a large and culturally diverse membership.

Other industries have established valuable precedents from which the oil industry could learn. One example is the Defense Industries Initiative (DII), which was founded in the US in 1986. DII signatories undertake to adopt integrity measures including a written code of conduct; a regular training program; the provision of a hotline-helpline; and participation in best practices forums.

More recently, the International Federation of Consulting Engineers has developed a set of guidelines for an Integrity Management System for consulting engineers. They are published at www.integritymanagement.org.

Capacity building

At a government level, the best defenses against corruption are strong, independent institutions backed by a vigilant civil society. The problem is that governments in many developing societies lack the manpower and technical capacity to build up such institutions, both at the national and-still more-at the local levels. This raises the question of what companies can do to support them.

Again, the answer is likely to lie in collective initiatives involving groups of companies or individual companies working with NGOs. The Makati Business Club in the Philippines is a good example of a business association sharing anticorruption expertise at the national level.

A valuable example of a set of bilateral initiatives comes from Denmark, where the Confederation of Danish Industries has been working with its counterparts in Tanzania, Ghana, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Lithuania, and China to build up their technical capacity.5 In turn, the local chambers have been advising their own governments on best practice, for example on commercial law reform-an issue with important implications for the fight against corruption.

Petroleum companies can and should play an important role in such initiatives.

Revenue transparency

A third area where collective initiatives are the most likely way forward concerns the transparency of oil revenues. Global Witness, a UK-based NGO, has highlighted this issue with respect to Angola. It argues that petroleum revenues have enriched Angolan government leaders and helped fuel the civil war, while the country's social indicators on matters such as health and education continue to decline.

The Angolan government has prime responsibility in matters of revenue expenditure. However, Global Witness argues that companies should at least declare the amount of revenue that they pay to the Angolan authorities. It will then be that much easier to judge what happens to the money once it enters the government system.

The problem is that the Luanda government actively discourages companies from making these disclosures, and individual firms fear that they may be penalized if they do so on their own initiative. BP has set an example by publishing its own revenue payments-only to receive a strongly worded note of protest from the Angolan authorities.

Financial transparency is a cardinal principle of international bodies such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. Both institutions are looking for ways of working with governments and companies to improve standards in oil-producing economies.

Meanwhile, in June international financier George Soros helped launch a "Publish What You Pay" campaign in London with the support of more than 30 NGOs. Soros calls on stock market regulators to require resources companies to report net payments to governments as a condition for listing.

Outlook for reform

No one seriously expects to eliminate corruption completely. There will always be loopholes. There will always be individuals with the imagination, determination, and greed to exploit them. However, it is possible to imagine a world in which business corruption is seen as exceptional rather than commonplace. It certainly should not be accepted as part of the norm in any society.

On the international scene, the most important indicator will be the effectiveness with which the OECD convention is implemented. At the national level, the most important task is to strengthen political and judicial institutions. Companies' first task is to implement high standards in their own operations. As discussed, this means both adopting the right policy and implementing it effectively.

A business commitment to integrity will carry costs. In some cases it may be necessary to stay clear of otherwise attractive projects in order to avoid unacceptable compromise. But the long-term rewards include a greater sense of security. A strong anticorruption stance is justified by enlightened self-interest.

In all scenarios the pace of change will be uneven in different countries and industries. Some countries will have better resources and more committed leadership than others. Some industries-including petroleum-will be more exposed to corruption than others because the rewards of graft are seen to be higher. Given that the stakes are so high, the oil and gas industry needs to take a lead in promoting international anticorruption initiatives. It cannot afford to wait.

References

- The countries were Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, the Philippines, Poland, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, and Thailand. The full survey appears on www.Transparency.org.

- Leite, C., Weidmann, J., "Does Mother Nature corrupt? Natural resources, corruption, and economic growth," IMF Working Paper, 1999.

- Fridtjof Nansen Institute/ECON Centre for Economic Analysis, "Petro-states-predatory or developmental?" Oslo, 2000.

- Fidler, S., Chaffin, J., "Enron revealed to be rotten to the core," Financial Times, Apr. 9, 2002.

- "Capacity building in industrial employers' organizations: The experience from Africa of the Confederation of Danish Industries," unpublished report, Copenhagen, 2001.

The author John Bray is policy director at Control Risks Group, an international business risk consultancy. He studied history at Cambridge University; has lived and worked in Kenya, India, and Japan; and has conducted short-term international assignments in a variety of locations. He joined Control Risks in 1983 and was head of research during 1988-96. His latest report, Facing up to Corruption: A Practical Business Guide, will be launched in October. It includes results of a survey of business attitudes toward corruption in the US, the UK, the Netherlands, Germany, Singapore, and Hong Kong.