This is the third year in which we have produced this overview of the prospects for Offshore Europe for Oil & Gas Journal (OGJ, Aug. 27, 2001, p. 58, and Aug. 14, 2000, p. 84).

Over the years the general theme that has developed is of the region being in the main a mature one (the only exceptions being on its deepwater frontiers). There has, as a consequence, been a lessening of interest by the major oil companies in the remaining prospects. These, in most instances, are very small compared with the giant fields of 20 years ago. A major exception to this trend is the discovery of Calgary-based EnCana Corp.'s Buzzard field in the UK, which has been steadily increasing in size over the past year as it has been further appraised and now seems to be capable of holding 1 billion bbl of original oil in place.

However, this broad-brush picture hides small gems. Many of the remaining small fields, given a suitable tax environment, can make good profits for the new generation of smaller operators that we have long forecast would appear.

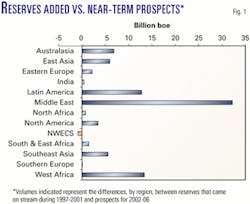

The Infield Systems database shows that, over the past 5 years, some 812 offshore oil and gas fields have been bought on stream worldwide with estimated reserves totalling 51.5 billion boe. For the period 2002-06, 1,180 fields are under consideration for development with estimated reserves of 100 billion boe. Most of these fields will probably be developed, but all too often the on-stream date is somewhat later than originally planned, due, it must be said, more to regulatory requirements than to technical challenges in most cases.

The average size of the 812 fields coming on stream over the past 5 years was 60 MMboe; the average size of the 1,180 development prospects is 115 MMboe. However, if the Middle East region is excluded, where 32 field prospects have sizes averaging 1 billion boe, the average size of prospects falls to 87 MMboe. Still, the overall trend is up. This reflects two things: the early stages of deepwater development and the increasing importance of natural gas. But both development cycles are in an earlier stage than that for more mature, shallow-water oil.

Fig. 1 shows that, when considering the individual regions, their offshore reserves that are under consideration for development over the next 5 years are greater than in the past 5 years. There is one notable exception, however: the Northwest European Continental Shelf (NWECS) area, the region that includes the North Sea. Although in absolute terms this figure for the NWECS falls only slightly, to 15 billion boe from 16 billion boe, its share of future 5-year prospects falls to 11% from 32% due to growth in other regions. In short, the message is that while offshore activity is set to increase in much of the rest of the world, the North Sea is now facing decline. One result is that the major operators have already voted with their feet and are investing an increasing proportion of their development dollars outside Europe in new, usually deepwater, areas of the world. One exception to the deepwater rule is the Middle East, where huge offshore gas fields are in prospect.

Whereas operational expenditure off Europe is likely to continue to rise for some years to come, capital expenditure is set for a dramatic decline, bringing with it some tough choices for many local suppliers if the relevant national governments do not make any moves to promote one of their major industries and employers.

As Table 1 shows, over the 5 years to 2001, new offshore oil and gas reserves totaling some 51 billion boe came on stream worldwide. The largest share was in European waters. Much of this was associated with the start-up of just one field, Norway's huge Troll gas field. Looking ahead to prospects slated to go on stream during 2002-06, these total some 135 billion boe and are dominated by the phased start-up of South Pars field in Iran. The first phase of this giant development is expected to hold some 5.8 billion boe and came on stream this year. Further phases (4-12) are expected to go on stream during 2004-09. The total may reach 25 billion boe at full development over 20 years.

Another major project in the Middle East-Central Asia region centers on Kashagan field in the shallow waters of the Northeast Caspian Sea. Although first touted as a 10-50 billion bbl structure, current estimates put its reserves at the lowest level of this range.

Natural gas is of increasing importance worldwide, but still 53% of the world's offshore reserves being considered over the next 5 years are liquids. There are some considerable variations from region to region, however. To give one example, in South and East Africa only 6% of the reserves are oil, whereas off West Africa oil accounts for 84% of expected production. With Kizomba A and B, Dalia, Benguela-Belize, Plutonio area, Bonga, Erha, and Akpo, the list of major West African developments seems endless at the moment.

Table 1 is not a forecast, as we do not expect all the future reserves shown to be bought on stream in the particular years for which they are slated, e.g., ChevronTexaco Corp.'s Agbami project off Nigeria. However, it does indicate the considerable prospects for the offshore industry in general worldwide and the major changes ahead for Offshore Europe in particular.

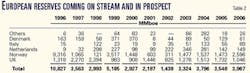

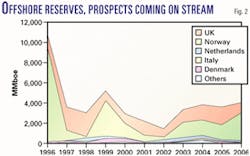

Fig. 2 and Table 2 show that the UK and Norway will continue to dominate new field development prospects off Europe. To some extent, the decline in 2001-02 is a delayed reaction to the oil price fall of 1998. Beginning in 2006 we see a significant decline in UK prospects and an increase in Norway, which has more opportunities in its northern waters, particularly the development of Sn hvit gas field-Europe's first LNG export project, allowing Norway the flexibility to serve markets its pipeline network cannot reach, such as the US East Coast.

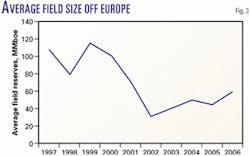

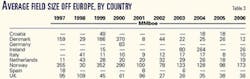

But for the NWECS region as a whole, Fig. 3 and Table 3 show that the overall trend of new reserves coming on stream is decidedly downwards. There will be dramatic reductions in the average size of new fields awaiting development for most European countries in the future if nothing is done to boost further exploration.

To counter this downward trend in new field sizes, it must be said that increased recovery rates in existing fields are showing an improving trend across the region. This has been particulary true recently in the chalk reservoirs of the Danish sector, where enough gas is now thought recoverable to allow export to the UK or eastern Europe.

European vs.global trends

Our analysis of activity off Europe compared with the rest of the world (ROW) shows some major differences in long-term field development trends.

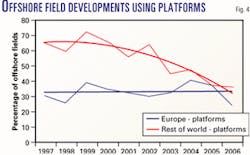

About 30% of fields developed off Europe entail the use of fixed platforms, and this percentage is staying reasonably constant (Fig. 4). The ROW total has at times exceeded 70%, but there is now a strong downward trend and a move towards floating production and subsea production as the infrastructure network has grown and moved out into deeper waters.

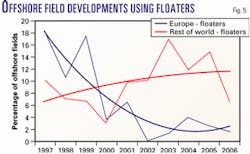

The use of floating production systems has declined off Europe and is expected to stay low. In other regions, however, the use of floaters is increasing as more fields are developed in deeper waters or remote locations in areas such as West Africa and the Gulf of Mexico (Fig. 5).

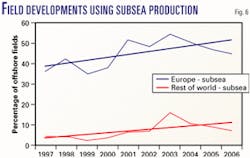

The North Sea has been the world's largest market for subsea production systems, and we expect this to continue as more fields are developed with subsea tiebacks. ROW percentages for this category are also increasing but from a smaller base (Fig. 6). At the moment all the large subsea projects seem to lie in the golden triangle of Brazil, West Africa, and the Gulf of Mexico. Outside of these three, Egypt is also seeing strong growth in subsea production.

Global forecasts

Moving away from prospects to a consideration of forecasts, there are four key expenditure sectors: deepwater, floating production, subsea, and pipelines.

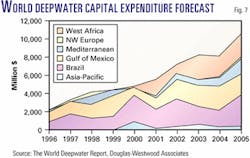

We expect global deepwater (500 m or greater) capital expenditure (capex), which was $5.6 billion in 2001, to grow to $10.6 billion/year by 2005-a total of $40 billion over the period (Fig. 7). West Africa is the region where we expect to see the largest capex growth, followed by the other deepwater hotspots, Brazil and Gulf of Mexico.

In many instances, floating production systems (FPSs) offer the only viable means of developing the more remote, deepwater fields. At present, the maximum tieback distance of a subsea oil satellite field to a host platform is some 45 km, in ExxonMobil Corp.'s Mississippi Canyon 211 Mica project in the Gulf of Mexico. While Shell Oil Co.'s MC 687 Mensa gas field has more than double that tieback distance, the flow assurance problems of gas flow over long distances in deep water are much less than those for often-waxy crude oil. But in all water depths, an FPS is often the development method of choice because of its flexibility and minimization of decommissioning costs.

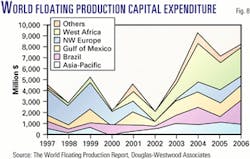

We expect capex on field developments using floaters to total $42 billion on 123 FPSs over the next 5 years (Fig. 8). This is mainly in West Africa, Latin America, and, to a lesser extent, Asia. Although North America has 20% of the forecast market by FPS numbers, it is only 11% by value due to the predominance of low-cost solutions such as production spars and mini-TLPs (tension leg platforms). Greatest capex growth is likely off Africa due to some very large field prospects. Only northern Europe, being a mature region, is expected to experience any significant decline.

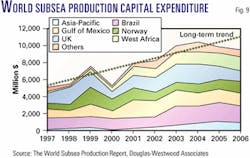

More floating production means more subsea wells, which together with subsea tiebacks to existing platforms will cause total subsea well numbers to continue their long-term growth trend. We forecast that annual spending for subsea wells will rise to around $10 billion/year from 2003 onward. Compared with the previous 5-year period-during which the estimated capex amounted to $31 billion-we forecast that 2002-06 will see a 50% growth in market value to just under $48 billion (Fig. 9).

Gas has been described as the fuel of the future, and global gas demand is growing even more strongly than that for oil. Across the world, more major subsea pipelines are being planned, especially to bring more gas to the UK and to mainland Europe-for example, Mara- thon Oil Co.'s proposed 800 km Symphony pipeline network to connect the UK and Norwegian sectors to Bacton in Norfolk, England (OGJ Online, May 15, 2002).

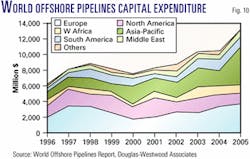

We expect the annual value of the world offshore pipelines market to grow to $13 billion in 2005 from about $8 billion in 2001 (Fig. 10). Europe will continue to form the largest segment at 29%, but we expect the largest future growth to be in the Asia-Pacific region due to the plans for large-diameter gas lines there.

It is likely that sometime after 2006 the UK will become a net importer of natural gas. Europe as a whole is also likely to experience a gas shortfall-hence the increase in pipeline expenditure as more lines to connect Europe to the major suppliers of Russia and North Africa continue. For instance, a major new pipeline project across the Mediterranean Sea is due to go ahead shortly. Called GreenStream, the 32-in., 570 km line will be laid in 1,150 m of water on its way from Libya to Sicily.

However, the main disadvantage of natural gas is that its largest sources (Russia and the Middle East) are far removed from major markets (and in the context of security of supply, it is very difficult to protect long-distance pipelines).

It is already evident that one major growth area in future years is likely to be that of gas converted to LNG. This will require increasing numbers of LNG tankers. Already plans are afoot to build two or more LNG regasification plants in the UK within the next 5 years.

We also expect to see a strong growth of interest in the use of floating production for natural gas conversion, either in the form of FLNG (floating liquefied natural gas) plants or FGTL (floating gas-to-liquids) plants. There are huge amounts of stranded gas offshore.

In most shallow-water regions of the world, the large fields have been developed first, with the result that considerable numbers of small fields await development. The Infield database lists 881 identified future field development prospects in water depths to 75 m. Present plans call for some 900 platforms to develop these fields, which are mainly located in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, West Africa, Latin America, and Northwest Europe, but by North Sea standards, these platforms will mainly be very small, less than 1,000 tonnes, and many probably very much smaller.

Offshore Europe prospects

Offshore Europe has always been a very different region compared with the other producing areas of the world, not the least for its harsh climate and consequent high engineering costs. As we have noted before, the region has also been complicated by the individual nations' very different approaches to the exploitation of their reserves. For the UK, the dash to generate oil and gas revenues to repair the economic chaos of the 1960s and 1970s led to what some might say was too rapid an exploitation of its reserves-with the result that practically all the large prospects have been developed. It is likely that only small fields remain unless enhanced exploration can discover more Buzzard-like fields to keep the momentum going.

Norway on the other hand, with its small population, was able to adopt a more managed approach to its developments and hoard away huge amounts of the proceeds to pay its citizens' future pensions. The result is that there are still some major prospects ahead but outside our time frame-one example being the massive and technically challenging Ormen Lange field and the potential for more lookalike structures in the Norwegian Sea (see related article, p. 28).

As a mature province, Offshore Europe now exhibits many of the characteristics shown earlier by the Gulf of Mexico-a great number of tiny, shallow-water prospects and a deep frontier. Europe now faces a very different future associated with these two extremes. In total there are 353 fields identified by oil companies as development prospects over the period to 2006. The problem is that the great majority of these are very small-by 2002, the average reserves of prospective fields have fallen to 31 MMboe, and by 2003, it is projected at 40 MMboe.

It is unlikely that the majors will wish to be significant players in this new game when they can invest in deepwater fields in other regions offering reserves of 10-30 times this size. A further opportunity arises for small players in taking over the operations of declining fields from the majors-this, of course, is dependent upon settlement of the decommissioning issues.

So overall, considerable numbers of opportunities will remain for players that are geared to the efficient production of small fields. In general, these are small oil and gas companies noted for their new thinking and being "fast on their feet." Examples include Consort Resources Ltd., a private equity-funded London firm with 20 employees and all operations outsourced. In the UK southern sector, Consort has interests in 12 UK Continental Shelf licenses, 6 producing fields, 6 fields under development, and 2 pipeline systems; is a gas buyer, seller, and shipper; and is the first company of its size to be granted operatorship of a UK offshore field.

Other notable companies include London-based Acorn Oil & Gas Ltd., whose first project is the redevelopment of the UK's first offshore oil field (OGJ Online, Jan. 16, 2002). Originally operated by Hamilton Bros. Ltd., Argyll field was the world's first to be developed with an FPS (the modified Transworld 58 semisubmersible drilling rig) and started up in 1975. The field and its satellites produced nearly 100 million bbl before abandonment in 1992. Licenses for the newly named Ardmore area development have been awarded to Acorn (35%) and Aber- deen-based operator Tuscan Energy Resources Ltd. (65%). This shows the potential not only for small players but also for applying 2002 technology to old or abandoned areas and begs the question of how many more opportunities exist for innovative thinking.

The other major consideration is the future for the region's service and supply industries. High levels of expenditure coupled with huge technical challenges have generated some world-class service and supply companies within Europe. However, they are now facing a major long-term problem: The large home market is set to decline as fields deplete and the size of new prospects reduces dramatically. The leading companies have great skills in the growth market sectors such as deepwater and subsea technology and are already global players, but there are also many companies that do not have exportable services. Therefore, in reality, it is unlikely that export activity can fully replace the home market, and a major reorientation of many of the region's suppliers is essential for the majority of its participants to have a long-term future.

However, the increasing involvement of the new small oil companies in the region also offers considerable prospects for some contractors. But new-era operators need new-era contractors, as they find it increasingly difficult to work with world-scale contractors that have been developed to serve the oil majors; there is an uncomfortable imbalance between a 20-person operator and a 5,000-person contractor.

Bibliography

Infield Systems' database contains details of existing and proposed global offshore field developments (www.infield.com).

The World Series of Reports are published by Douglas-Westwood (www.dw-1.com).

The authors

John Westwood heads the industry analysts Douglas-Westwood Associates and has, over the past 16 years, been responsible for over 120 specially commissioned oil industry business studies. He previously spent 12 years working in the underwater contracting industry; has established, expanded, and sold two offshore industry companies; and has served on the boards of offshore industry companies in the UK and Norway. Westwood has published over 60 papers and is joint author of a number of worldwide industry reports published by Douglas-Westwood Associates. His e-mail address is [email protected].

Roger Knight has spent the past 15 years responsible for the collection, validation, and evaluation of the global offshore oil and gas data held on the Infield Systems database. He holds a PhD in geology and is a member of the Institute of Petroleum. Prior to the Islamic Revolution, Knight worked as a university lecturer in petrology and structural geology in Iran. He is the author of a number of papers on the offshore oil and gas industry and is joint author of a number of worldwide industry reports published by Douglas-Westwood Associates. His e-mail address is [email protected].