What tax reform in Russian oil industry really means for investors

The Russian oil industry's taxation system-established during the previous decade-is inflexible, basically revenue-based rather than profit-motivated, overcomplicated, and fiscally oriented. In order to improve it, the Russian government has introduced a new, simplified tax system for the industry in the recent draft, "Russian Energy Strategy for the Period to 2020," the guidelines of which the government approved Nov. 23, 2000.

Implementation will consist of three main components: a profit tax, a severance tax (on extraction of mineral resources), and an incremental revenue tax (IRT). Each of these components is designed to extract a particular portion of oil-related economic "rent:"

- Profits tax. With this tax, the state will levy a portion of revenue from all subjects of entrepreneurial activity-in all spheres of the economy.

- Severance tax. With a severance tax, the state intends to levy a "mining rent" or fee from all entrepreneurs actively engaged in the extraction of mineral resources. This revenue will be based solely on extraction of natural resources, not present in other economic spheres.

- IRT. The state intends to levy IRT on entrepreneurs engaged in the extraction of mineral resources that operate sites or develop projects located in more-than-normally favorable natural conditions. The tax would be on a portion of the "differential rent" (or excess revenues or profits) received due to such better natural conditions.

Under the general subsoil use licensing system, this tax regime will be governed by administrative (public) law, with all three taxes unilaterally fixed by the state. Under production sharing agreements based on contract (civil) law, the IRT will be replaced by production sharing established through negotiations.

The first two elements of this three-chain taxation system became effective Jan. 1, via the introduction of relevant chapters of the Russian Federation's tax code. The president of the Russian Federation signed these relevant laws in August 2001. The profits tax rate has been reduced, its administration has changed, and a new severance tax (on extraction of mineral resources) was introduced to replace several taxes subsoil users previously paid (OGJ, Aug. 13, 2001, p. 54). This completes the first stage of Russia's planned tax reform. The work on the IRT draft law is still going on. Work on a special chapter of the tax code devoted to taxation under PSAs continues as well.

Impact on investors

How can the efficiency of the implemented reforms be evaluated from the investors' point of view? Experts of the Moscow-based Energy and Investment Policy & Project Financing Development Foundation (ENIP&PF), which the author headed prior to accepting his current position, prepared an analysis, the full version of which will be published soon in Russia. Details can be found on the web site of the ENIP&PF (www.enippf.ru).

The main conclusions of the analysis, however, are as follows:

Preliminary conclusions show that tax reform in the oil industry has not been properly balanced at the current stage. The introduction of the severance tax and the review of the profit tax, on the whole, discourage investment and only serve as the means for resolving the state's fiscal problems. The government's main target is securing as much in tax revenues as possible from producers of mineral resources in order to have a budget surplus required-first and foremost-to finance social expenditures such as wages and pensions and to be able to make unprecedented high payments on Russia's foreign debt in 2003.

The reforms have failed to make the tax system both more transparent and effective. Transparency has prevailed over efficiency. Rather than growing more efficient, the tax system has become more primitive. The only oil companies that can benefit from the introduction of those new tax instruments are those seeking to maximize their current financial flows and exports while minimizing investment activities.

Small and medium-sized companies and nonintegrated upstream companies are definitely among the main losers. Under current conditions, the introduction of any mechanism of the IRT -the third element in the new tax system for the oil industry-can only further discourage investment.

As competition in the world markets of oil and capital has toughened, potential strategic investors' interest in Russia's oil and gas may further flag, and borrowings by Russian oil companies to finance their oil and gas projects in the country may grow more expensive. As a result, this kind of tax reform may lead to Russia's losing its competitive position in the world oil and capital markets, and liquid fuel may even lose its ability to compete in the domestic energy market.

To avoid that, tax reform should have a complex nature, ensuring a balance of the state's fiscal and investment interests. Striking a balance of interests at the macroeconomic level should be the main objective for the state when it works up and pursues an effective economic policy.

Profits tax

The new procedure for the profits tax is established by Chapter 25 of Russia's tax code. The main innovations are the reduction of the profits tax rate to 24% from the current 35% in return for cancellation of all allowances applicable to profits tax payment. This includes the investment allowance that currently allows companies to write off 50% of the taxable amount from the taxable base calculated for the profits tax, under the condition that such amount is used as investment.

It also provides the Russian Federation's state authorities the option of giving profit tax concessions in an amount of up to 4 percentage points from the portion of such tax payment that is transferred into the state budget, which may result in the effective profit tax rate's being just 20% (see table).

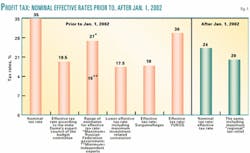

The cabinet and many parliament members regard the reduction of the profits tax rate as a strong incentive for investment. But the effect of the diminishing tax rate cannot be evaluated separately from the effect of the investment allowance cancellation, because it is not the nominal tax rate that matters, but its effective rate.

Under the new system, the nominal and effective profits tax rates will be equal-all the deductions of the tax are canceled. But prior to 2002, the nominal and effective profits tax rates have differed significantly.

The implementation of the profits tax incentives, and primarily the investment allowance, has been a widespread practice in Russia. According to the Russian state Duma budget committee, the actual profits tax rate with all tax breaks was 19.5% on average for Russia in 2000, compared with its nominal rate of 35%. When the tax code's Chapter 25 was debated, government officials estimated the effective profits tax rate at 27%, while independent analysts assessed it at 15-17% (Fig. 1).

Various companies have not enjoyed similar investment allowances. Smaller and midsized, nonintegrated companies have been particularly keen on using them. As a rule, they work in smaller and midsized fields with hard-to-recover reserves and get their share of economic rent through "effect of specialization," which requires more expensive technologies. For that reason, the ratio of annual capital investment to production volumes is higher for smaller and midsized companies than for vertically integrated ones (VICs)-by 1.5 times in 1999 and 5.5 times in 2000 for companies operating in Russia. This explains why smaller and midsized companies have used investment allowances to the utmost, and their loss will be particularly painful for those firms.

But a different effect of the profit tax reform does exist in a group of the vertically integrated companies as well. To a company with long-term production plans, such as OAO Surgutneftegas, that used to pay an effective profits tax rate of, say, 18% and is maximizing oil-related priorities and implementing its investment program to expand production capacities, the tax reform means an effective growth in the tax burden by 6 percentage points (to 24% from 18%).

But VICs, such as OAO Yukos, for which the actual profits tax rate was, for example, around 30%, that are maximizing current cash flows and thus are continuing to 'eat away' available reserves on their balance sheets-which they, like other Russian VICs, got mostly for free in the early 1990s-will see their tax burden eased, due to the reform, by the same 6 percentage points (to 24% from 30%).

The reason is that the owners and managers of the VIC-which has usually come into the oil business in the mid-1990s in the course of the Russian "loans for shares" campaign-focus on its short-term financial priorities in a broader range of their businesses and do not necessarily intend to go on working in the sector in the longer run. Rather than laying the foundation for future production, such a company is interested in increasing its current capitalization, using all possible means to add as much reserves as possible to its balance sheets, so owners can sell the business profitably.

Therefore, for the oil companies conducting intensive investment activity, the reduction of the nominal profits tax rate in return for the cancellation of the investment incentive actually means an increase of the effective tax burden, even taking into account the availability of the regional profits tax incentive.

Severance tax

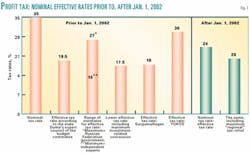

This new severance tax and its levy procedure are outlined in the tax code's Chapter 26. The severance tax on the extraction of mineral resources replaces royalties, payments on the restoration of mineral resources, and the excise tax, except those for natural gas. According to Russia's Ministry of Finance, the severance tax is introduced as a mechanism that would ensure a tax burden equivalent to the taxes it replaces but would simplify the taxation and make it more transparent. This way the Ministry of Finance fixed the basic tax rate at 16.5% of gross revenue-8%, 6%, and 2.5% are the actual, effective rates for royalties, mineral resources payments, and excises, based on the weighted average prices of oil supplied to the domestic market and exported. Their nominal rates and budget allocation are presented in the table on p. 24.

The rate of 16.5% will only be applied from 2005 on. For PSA projects, half the rate will be used, although it has not been specified whether the reduced rate will be effective in 2002-04. For projects implemented under the general license system by companies financing initial exploration with their own funds, the severance tax rate will be 30% lower than the basic rate.

During 2002-05, a special rate of the severance tax will be levied, equal to 340 rubles/tonne, adjusted to the ruble's hard currency rate against the dollar and changes in world prices of Russia's Urals export blend. At this initial stage, the severance tax will serve as a means of combating transfer prices. For that reason, a specific rate is fixed, rather than an ad valorem rate.

For hydrocarbons, tax revenues are shared 80:20 between the federal budget and the budget of a relevant region. For regions with a complex legal structure, where hydrocarbons are produced in an autonomous district within a region, the federal budget gets 74.5%, the autonomous district 20%, and the region 5.5%. For production on Russia's continental shelf or in its exclusive economic zone, the full amount of the tax goes to the federal budget (table, p. 24).

Fig. 2 shows the effect of the severance tax introduction within the period 2002-04 compared with the effect of payments it has replaced:

a) under the current licensing system applied to:

- Fields under development (mean values curve, i.e., average conditions: royalty = 8%; payments on restoration of mineral resource = 6%; excise tax = 2.5%).

- New fields, taking into account the deterioration of natural conditions of the mineral resources and execution of exploration activities by the companies at their own costs (minimum values curve, i.e., deteriorated conditions: royalty = 6%; payments on restoration of mineral resource = 0; excise tax = 2.5%).

b) undeer PSA projects (mean values curve, i.e., average conditions: royalty = 8%; payments on restoration of mineral resource = 0; excise tax =0).

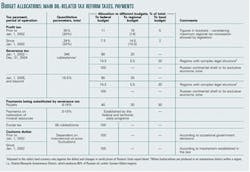

As seen in Fig. 2, the introduction of the "specific" rate for the severance tax eases the tax burden on fields previously developed under the general license system for virtually any price level-prices higher than $35/bbl for Urals are very unlikely-but only under the most favorable scenario for oil companies if they can export 100% of produced oil.

But the tax burden grows for new fields developed under the general license system and for any PSA project if prices are higher than $14/bbl for Urals, according to ENIP&PF estimates.

We do know all relevant price estimates for the near future. For example, those used to compute the 2002 Russian federal budget's revenues ($23.50/ bbl) and expenditures ($17/bbl). The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' target price band, and the International Energy Agency's forecast all exceed this level. The "fair" price range-$20-25/bbl-mentioned by Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov and other Russian officials many times, is also higher than the break-even $14/bbl level. In recent years, it was only a period from early 1998 to early 1999 when oil prices fell below the break-even level as a result of the "Asian crisis" (Fig. 2).

So the implementation of the specific rate for the severance tax during 2002-05 actually increases the tax burden on new projects and PSA projects, i.e., on those projects that are definitely needing investments, and-within the anticipated price range-discourages investment.

If estimates are made for actual shares of exports, rather than for 100% exports, the situation is much worse for various groups of companies. In our study, we have estimated the consequences of the severance tax's introduction for various groups of companies (VICs and small and medium-sized companies) with various export quotas (30%, 60%, and 100%), for projects implemented in various natural conditions.

The overall conclusion is that the lower the share of exports is in a company's production, provided that all other conditions are similar, the lower is the critical level of world oil prices under which-taking into account of the margin between domestic and world prices-the production tax is higher than the combined taxes it replaces (Fig. 3).

The absence of a mechanism for differentiation of severance tax collection based on various stages of investment projects-initial, mature, final, or declining-or based on qualitative parameters of the developed fields, such as API gravity or sulfur content, does not create adequate incentives for the potential investors either.

The single fixed "ad valorem" severance tax rate to be applied to all projects from 2005 on, instead of the fixed rate for each project in a wide interval of the allowed values-as happens today with regard to royalty-means a real increase of the tax burden for all categories of subsoil users. For the PSA projects, it is true in all price intervals. The severance tax equals 8.25% instead of the effective royalty rate equal to 8%.

The PSA investors have in principle an opportunity to compensate for such an increase of the tax burden in the course of their negotiations with the state, proving the bigger profit-oil split in their favor. For the projects developed on license terms, the transition to the severance tax means an increase in the tax burden when crude oil prices exceed $12/bbl or 2,600 rubles/ tonne. The market price of crude oil in the internal Russian market, or sales price between nonaffiliated third parties, steadily exceeded this level in 2000-01.

The internal wholesale price of crude oil reflects transfer prices of the VICs and during 2000-01 modestly grew to 2,000 rubles/ tonne from 1,500. There is a high probability that by 2005 it will exceed the threshold level of 2,600 rubles. Thus, under the licensing system and under the PSA, after 2005, the severance tax will generate a heavier tax burden for the oil companies compared with the current tax system.

Customs tariffs

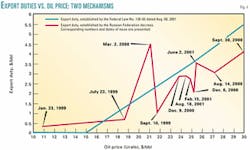

On Jan. 1, new rates also took effect for oil export tariffs. The most important innovation here is that tariff rate caps are at long last fixed by law. This law fixes the mechanism for defining customs tariffs, which corresponds to the ratio of prices to tariffs at the moment the law was adopted.

Our analysis shows that, within the ranges of expected world prices at or exceeding $17-18/bbl, or according to Kasyanov's definition of fair prices of $20-25/bbl, the tax burden on oil companies due to export tariffs will be somewhat higher than that previously established by the government's ordinances (Fig. 4). This is certainly bad for oil companies.

But, in my opinion, there are two positive things outweighing this negative aspect. First, there is now rigid dependency-which did not exist before-between the level and dynamics of world prices, on the one hand, and the level and dynamics of export tariffs, on the other.

Second, the fact that customs tariffs are fixed by law is positive for investment activities. The government has finally ceded the ability to fix new customs tariff rates at its own discretion, which formerly made it hard for oil companies to plan their taxes, as tariff rates were unpredictable from quarter to quarter.

The government regarded customs tariffs as a tariff regulation instrument. It obviously used it to resolve its budget problems, which perhaps explains abrupt changes in tariff rates fixed by governmental ordinances (Fig. 4). Customs tariffs fixed by law reduce investment risks and the cost of borrowing for oil projects, creating greater stability, customs tariff predictability, and the transparent mechanisms for fixing them. F

The author

Andrei A. Konoplyanik is the newly appointed deputy secretary-general to the Energy Charter Secretariat in Brussels. Previously, he was president of the Moscow-based Energy and Investment Policy & Project Financing Development Foundation. Since 1993, he has held a number of advisory positions with the Russian Federation government, including the Russian Ministry of Energy, and has served on state Duma committees. During 1996-99, he was executive director of the Russian Bank for Reconstruction & Development in Moscow. Konoplyanik received his PhD in energy economics at the Moscow Institute of Management and earned a doctorate of science from the State Academy of Management. He has published more than 300 articles in Russia and abroad.