Russia's oil majors:engine for radical change

It is hard to believe that merely a decade ago the Soviet oil empire-the largest oil industry ever built-was falling apart, burying under its debris the biggest centrally planned economy.

Within 10 years, Russia's crude oil output shrank by nearly half, from 11.5 million b/d in 1988 to only 6.1 million b/d in 1998, with no visible signs of eventual recovery.

Recently, with over 7.4 million b/d of crude production, Russia has outstripped Saudi Arabia as the world's leading oil producer and is set to hit 10 million b/d around 2010.

However, this unexpected development is no longer controlled or financed by the state. On the debris of the state-run oil distribution system there have arisen new major private companies, vigorously building their own "petropreneurship" and paving their way to the world oil business.

Russian oil majors categorized

The radical reorganization of Russia's oil sector, which began at the end of 1992, and the hasty sell-off of state oil property, which started in fall 1995, have dramatically changed and continue to change the still unstable corporate structure of the industry.

Its denationalization and decentralization have opened up the Russian oil market to hundreds of new players with diverse origin and ownership: private, cooperative, municipal, public, joint-stock, joint-venture, and foreign entities operating both upstream and downstream but primarily involved in crude and product trading. Still, less than a dozen major, vertically integrated oil companies-which were formed in 1992-98 and are now mostly privatized (see related article)-constitute the cornerstone and the backbone of Russia's present-day, clearly oligopolistic industry.

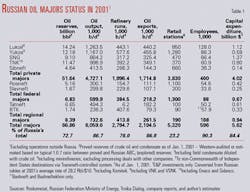

Although all the Russian majors are big producers and sellers of crude and products, they differ in some other respects-first of all, with regard to their ownership and scope of operations. With this in mind, the Russian major oil companies can be conventionally divided into three fairly homogenous groups: private majors, federal state entities, and regional players.

The group of private majors includes the six largest oil companies with zero or only symbolic state participation and countrywide operations: OAO Lukoil, OAO Yukos, Surgutneftegaz (OAO SNG), Tyumen Oil Co. (TNK), and Siberian Oil Co. (Sibneft). Until recently, this grouping of privatized and independent companies included the once powerful Sidanco Oil Co., whose oil production shrank last year to a modest 180,000 b/d (or 2.6% of Russia's total output) and which is now effectively controlled by other majors-by the Russian TNK (69.3%) and the international supermajor BP PLC (25%).1

The formerly dominant group of federal state majors is now represented by the 100% state-owned Rosneft and the Russia-Belarus state-controlled JSC Slavneft. It is noteworthy that this group of integrated oil firms does not comprise other Russian state-run companies working in specific areas of the oil business, such as the 100% state-owned Zarubezhneft, which operates exclusively abroad; the 75% state-controlled Transneft, which almost fully monopolizes Russia's crude oil shipments by pipelines; and the 75% state-owned oil product pipeline monopoly Transnefteprodukt.

As for the regional majors, this specific grouping of unevenly integrated enterprises includes two partly privatized oil companies, Tatneft and Baskir Fuel Co. (BTK), which basically operate in the Volga-Urals republics of Tatarstan and Bashkortostan and are virtually controlled by the respective republics' governments. The poorly integrated Tatneft (which lacks its own refining capacity in Tatarstan) is more internationally oriented both upstream and downstream and is well-known on the world stock and capital markets. In this respect, the partly state-controlled Tatneft tends to gravitate towards the first group of private majors and often joins their ranks in protecting common business interests. In turn, the internationally shy and regionally focused BTK is a rather self-reliant energy conglomerate, embracing local oil production, refining, transportation, and power generation.

A well-informed reader could have added some more names to the above short list of regional players. However, for various reasons, they would no longer qualify as major oil companies. Some of them-such as the Siberia-based Eastern Oil Co. (VNK), East Siberian Oil & Gas Co. (VSNK), Komitek in the Komi Republic, and Orenburg Oil Co. (Onaco) in the Orenburg region-were swallowed by Yukos, Lukoil, and TNK. As for the semiprivate Sakhaneftegaz, which integrates gas and oil operations in the far-eastern Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), and the wholly state-owned Groznefte- gaz, which was set up to protect and restore oil facilities in the Chechen Republic, they are (as yet) too small to claim a major's status.

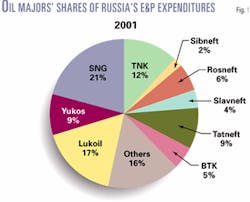

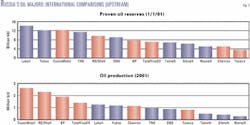

Hence, there are nine independent companies in Russia that can be currently regarded as oil majors, with only five of them (Lukoil, Yukos, SNG, TNK, and Sibneft) embodying all the classic features of a large, integrated, and not fully state-owned (national) oil company (Table 1, Figs. 1-2).

Relative size

Despite controlling sizable portions of the country's oil business and vigorously muscling into foreign-based operations, so far the Russian majors can be compared with their international peers only in terms of oil reserves and production.

In particular, according to Western audits, even without its foreign assets, Lukoil's proved oil reserves (14.2 billion bbl) exceed those of ExxonMobil Corp., which are roughly equal to Yukos's (12.2 billion bbl). In turn, TNK (11.5 billion bbl) controls more proved oil than does Royal Dutch/Shell Group, while SNG's reserves (9.1 billion bbl) outstrip those of BP PLC.

As for oil output, Russia's largest producers-Lukoil (1.3 million b/d) and Yukos (1.2 million b/d)-have already surpassed Chevron Corp. (prior to its merger with Texaco Inc.) and tread on the heels of TotalFinaElf SA.

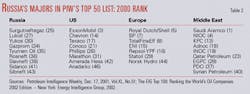

Admittedly, the Russian companies' current achievements in downstream and in total sales are much less impressive. Still, in the latest Petroleum Intelligence Weekly ranking of the world's top 50 oil firms, Russia's majors occupy more places than their peers from the US or Western Europe and as many slots as oil companies of the Middle East (Table 2).

Comparing the Russian oil majors with other, nonoil companies by their market capitalization gives another useful dimension. According to Financial Times' latest ranking of the world's largest companies (published in early May and grading companies by their market capitalization as of Mar. 28), Russia has four entries in the global Top 500 list-all in oil and gas: Yukos (in 227th place with $18.74 billion), OAO Gazprom (250th, $17.36 billion), SNG (344th, $13.16 billion), and Lukoil (362nd, $12.53 billion).2

Logically, the Russian oil majors also look much better on a regional-East European-basis. This year's rating by Financial Times has given them (and their controlled firms) 12 places in its Eastern Europe Top 100 list, including 4 out of the first 5 places. A similar and almost simultaneous ranking by the Russian Kommersant newspaper appears to be more thorough and, as such, includes 18 Russian oil companies in its own list of 100 biggest East European companies (Table 3).

Who controls them?

The quick and all-out privatization of Russia's oil companies has dramatically changed the patterns of their ownership and management. With very few exceptions, new "masters" of Russia's oil majors are influential Russian financiers and tycoons who managed to buy actual control of the privatized oil companies owing to accumulated cash resources and implicit government support.

On the surface, virtually all the known major acquisitions (Table 4) were made by previously unknown, oil-related investment firms (Laguna, NFK, Interros Oil, Sins, Refine Oil, Monblan, FNK, Novy Holding, and Noviye Prioritety) that were set up to bid for tendered state shares and to camouflage the interests actually involved. Still, it became eventually known that such ambitious commercial banks (like Unexim, Menatep, SBS-Agro, Alfa, and NRB) and well-known Russian oligarchs (such as Vladimir Potanin, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Roman Abramovich, Boris Berezovsky, and Mikhail Fridman) had been standing behind the successful bids of these investment firms.

Thus, the hasty privatization of Russia's oil took the form of its swift seizure by a handful of commercial banks (and financiers) that took less than 2 years to take over the biggest oil companies. At the heyday of Russian oil's "bankization" (i.e., prior to the August 1998 financial crunch), directly or through affiliated firms, Khodorkovsky's Menatep Bank controlled 84.7% of Yukos and 54.2% of VNK; Potanin's Uneximbank, 86.5% of Sidanco; Smolensky's SBS-Agro Bank, 51% of Sibneft3 and 85% of VSNK; and Gazprom-affiliated National Reserve Bank, 67.3% of Komitek. As for Fridman's Alfa Bank, it still controls 50% of TNK with all its newly acquired assets (Onaco and Sidanco).

Admittedly, virtually none of these oil assets is owned (or used to be owned) by the banks directly. As it was noted by Petroleum Argus's FSU Energy, "ellipsein Russia what is important is what you control, not what you ownellipseGood political links are essential whether you are seeking to win a privatization auctionellipseor to get your people into a position where they can milk another company's assets."4

Not surprisingly, the best-connected financial moguls are known to head and actually manage most of the privatized oil majors, while publicly disclaiming any personal holding interests.

In the aftermath of the August 1998 financial crisis, the impoverished Russian banks could no longer use their shrunken financial resources to buy into the national oil business. Besides, the concurrent slump in oil prices transformed the acquired oil assets from cash cows into financial liabilities. This led Russian financial groups to distance themselves from the once-lucrative business or to divest their oil holdings entirely. Hence, by 1999, the period of the state-backed "bankization" of Russia's oil had come to its logical end.

Nevertheless, three of the Russian private majors (Yukos, TNK, and Sibneft) are still controlled and even personally managed by financial magnates, while the other two (Lukoil and SNG) are run by the old-guard "oil generals" who also belong to the cluster of well-known and richest Russian oligarchs.

Still, in many cases, shareholding structures of the private oil majors is quite obscure, if not completely closed, with regard to disclosure of personal holdings. Major owners of oil stock ordinarily refrain from exposing their involvement in the "biggest business" to the public, criminals, and tax-collectors. "Most of them now live modest lives, and they can walk down the street without a bodyguard," explained Khodorkovsky, head of Yukos. "If others find out that someone is wealthy, that is the end of his personal life. And the taxman will call."5

Why they go abroad

At the dawn of perestroika-the restructuring of the Soviet Union's economy-most of the new oil entities started to set up their own joint ventures with many Western oil and service companies in order to revamp producing oil fields, to reactivate idle wells, and, surely, to launder much-desired hard-currency earnings.

But as the lust for currency was mainly satisfied and the grown-up JVs began to compete for congested export outlets with their own Russian parents, the latter became increasingly xenophobic and nationalistic. As production-sharing contracts were introduced and the formerly unavoidable marriage with a local partner was no longer needed, Russian majors and their oil-producing subsidiaries began to claim sizable stakes in multibillion-dollar foreign-backed projects in Sakhalin, Siberia, Timan-Pechora, and the Barents Sea-regardless of available finances, technology, and management skills.

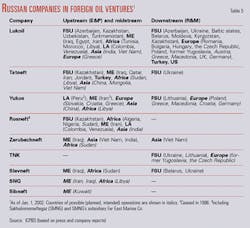

The most ambitious and aggressive companies (such as Lukoil, Yukos, and Tatneft) dared to risk their limited capital and reputation in the former Soviet republics as well as in Eastern Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and even in the Americas. To facilitate their penetration into the world oil trade, internationally minded Russian majors such as Lukoil, Yukos, Sidanco, and Slavneft set up their own representations and trading firms in Geneva, Vienna, London, Brussels, Houston, and other world oil capitals.

As oil export revenues increased but domestic taxation remained unbearable, the Russian oil majors' interest in overseas ventures and lucrative markets became ever stronger. The windfall profits of 2000 prompted most of Russia's majors to vigorously seek lower-risk, higher-profit investment projects outside their home country-away from the endless nonpayments, insatiable bureaucrats, and ever more persistent tax-collectors. Besides, buying into East European downstream and midstream sectors has a special raison d'être-securing direct access and massive crude supplies to local refineries fenced otherwise by expensive middlemen (see related article).

Last year saw a real upsurge in the Russian companies' overseas activities, with Nigeria, Algeria, Qatar, Sudan, Morocco, and Colombia as well as project proposals in Iraq having been added by Lukoil, Rosneft, Slavneft, and Tatneft to their lists of foreign-based exploration and production ventures. In addition, Lukoil and Yukos expanded their midstream and downstream operations in Europe (Slovakia, Poland, Lithuania, and the former Yugoslavia). By now, Russian oilmen operate or intend to launch new ventures in some 40 foreign countries on almost all the continents (Table 5).

Why so cheap?

The Russian majors are rushing abroad even though the country's oil assets look so teasingly cheap to acquire.

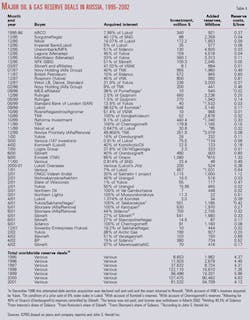

It is hard to believe, but the biggest chunks of the state oil property were pledged and sold in late 1995 for 3-11¢/bbl, while, say, nearly 1 billion bbl of proved oil controlled by VSNK changed hands for only 1¢/bbl. Understandably, foreign strategic investors (ARCO, BP, and India's Oil & Natural Gas Corp. unit ONGC-Videsh) had to buy their highly promising "entry tickets" at higher prices-$0.40-$1.10/boe-which is also typical of the later strategic purchases by the Russian oligarchs and of some public sell-offs of Russia's largest companies, such as SNG, Lukoil, and Yukos (Table 4).

Still, even now, reserve-related acquisition costs in Russia are, on average, a fraction of the $4-7/boe typically recorded in recent years in major reserve deals worldwide (Table 4). Average acquisition costs for Russian oil and gas reserves were 32¢/boe in 1997, 21¢/boe in 1998, 11¢/boe in 1999, 71¢/boe in 2000, and 34¢/boe in 2001.

There are two main reasons for these unbelievably inexpensive oil reserve purchases of Russian oil assets.

First, most of the publicly sold assets are not really available on a competitive basis. The Russian oil majors have enough political leverage and economic power to fence off all those auctions and tenders from undesirable competitors and to "compete against themselves," ensuring the lowest winning bids. Besides, squeezing minor resourceful companies out of business and then cornering their hopelessly cheap stock is a fairly widespread predatory practice among the Russian majors trying to establish their dominance in promising oil-producing regions.

Second, the low acquisition costs reflect the notoriously high investment risks typical of doing oil business in Russia. Few foreign investors would make a competitive bid for Russian oil assets without having substantially trimmed it down to allow for the high investment risks.

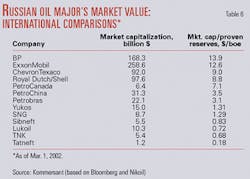

Consequently, Russia's oil pool is not yet opened to international competition, so the extremely low reserve-acquisition costs must be seen as an entirely indigenous phenomenon, clearly mirrored by the correspondingly low reserve-related market capitalization of Russia's oil majors. Not surprisingly, the reserve-related market value of the Russian oil majors is still much lower than that of the international majors as well as their Canadian and even Chinese and Brazilian peers (Table 6).

International attractiveness

Understandably, as Russia's investment climate improves, the Russian majors' undervalued stock will become more attractive (and, consequently, more expensive) for foreign investors.

"I think market ratios of Sibneft must be comparable with those of Western, at least regional, oil companies," argued Yevgeny Shvidler, president of Sibneft. "I cannot justify any discount based on the fact that we are a Russian company. We are set to achieve Western companies' levels by all the yardsticks.''6

"By now we understand how business is done in the West," said Khodorkovsky. "As a shareholder, I earn money in dividends and with the increase in the market capitalization of my company."7

Anyway, by the time of the international majors' probable reentry into the Russian play, the nation's underpriced (and poorly managed) assets may appear to be completely redistributed among competing Russian majors. Even now, the Russian minister for natural resources, Vitaly Artyukhov had to admit that "all reserves of any noticeable significance are already divided; the partition of subsoil is over."8

This may make some international majors (such as BP, TotalFinaElf, and Shell) reconsider their shelved joint ventures and postponed strategic alliances with the most attractive Russian counterparts. However, not only is a partner's resource potential taken into account, but the quality of its corporate management, financial performance, and operating milieu is also given close consideration.

No doubt, the Russian oil majors-and, particularly, the five biggest majors-symbolize and shape Russia's modern oil business, being the main driving force of its radical transformation and dynamic growth.

However, despite the new oil masters' ambitions and aspirations, the ongoing internalization of Russia's oil industry is still hindered by the financial weakness of the country's oil majors, while their competitiveness vis-a-vis Western counterparts is still seriously undermined by the lack of market-oriented management.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for invaluable information and useful observations kindly shared with him by Russian leading oil investment analysts, including Valery Nesterov (Troika Dialog), Gennady Krasovsky (Nikoil), and Alexey Stepanov (Lukoil). Still, none of them should be supposed to assume responsibility for any opinion expressed by the author or any factual error that may be found in this article.

References

- Although 84.3% of Sidanco's equity was formally held (since mid-2001) by Cyprus-based Sborsare, this offshore firm is totally controlled by Alfa Group and Access/Renova, which, in turn, equally own TNK Industrial Holdings Ltd. The latter fully controls TNK International Ltd., based in the British Virgin Islands and holding 97.1% of Tyumen Oil Co. (TNK) as well as over 90% of Orenburg Oil Joint-Stock Co. (Onaco). Last April, 15% plus one share of Sidanco was bought from Sborsare by BP PLC, which added the new stock to its previous 10% interest in Sidanco to form a blocking stake.

- Financial Times, May 10, 2002.

- Before SBS-Agro went broke in 1998, its chairman and owner, Alexandr Smolensky, controlled 51% of Sibneft through his Oil Financial Co. (NFK), while Roman Abramovich and Boris Berezovsky kept another 46% of the company through their three firms, Runicom, Refine Oil, and Sins. At present, up to 88% of Sibneft assets are reportedly controlled by Abramovich (perhaps equally with Berezovsky).

- FSU Energy, Apr. 16, 1999, p. 2.

- Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, Feb. 25, 2002, Vol. XLI, No. 8, p. 7.

- Kommersant, May 7, 2002, p. 12.

- Forbes Global, Mar. 18, 2002, p. 39.

- www.strana.ru/stories/02/02/ 26.

The author

Eugene (Yevgeny) Khartukov is general director of the International Center for Petroleum Business Studies (ICPBS), Moscow; head of World Energy Analysis & Forecasting Group (GAPMER), Moscow; vice- president (for Eurasia) of Petro-Logistics, Geneva; and professor of management and marketing at Moscow State University of International Relations (MGIMO). E-mail address:[email protected].