Oil Markets teetering on brink of oil price spike or collapse in 2002

Has there ever been greater uncertainty for the direction of oil prices?

The oil industry at the outset of 2002 stands poised on a dual precipice: an oil price spike or collapse. Either or both could happen this year.

At this writing, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and chief non-OPEC oil exporters were establishing an uneasy rapprochement over the scope of oil production cuts needed to right the market again. It seemed likely that enough non-OPEC cuts would be forthcoming to trigger the 1.5 million in cuts OPEC pledged to undertake Nov. 14 and carry out at Cairo Dec. 28 on condition the non-OPEC nations would meet a threshold cut of 500,000 b/d (see Newsletter, p. 5). Whether that rapprochement survives the turn of the year was idle speculation at presstime. Whether this new OPEC confrontation with non-OPEC exporters dissipates or worsens, however, will determine the extent of downward pressure on oil prices this year and perhaps for years to come.

At the same time, the US-led coalition against terrorism was tightening the noose on Osama bin Laden and the Taliban in Afghanistan, and Washington, DC, was already sounding an early drumbeat for the next stage of the campaign: Iraq.

Whether an Iraqi oil supply disruption is in the cards will determine the extent of upward pressure on oil prices this year. Whether there is a domino effect involving other key exporters affected by civil unrest over the antiterrorism campaign or by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict could also determine the outlook for oil prices for years to come.

Post-Sept. 11

This dizzying dual scenario has its roots in the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks on the US.

The relationship of the antiterrorism campaign targeting Iraq and the events of Sept. 11 speaks for itself. But the OPEC vs. non-OPEC standoff warrants explanation.

The remarkable cohesion of OPEC in ratcheting oil supply up or down to fine-tune oil prices to within a desired range of $22-28/bbl (for a basket of OPEC crudes) had yielded the strongest oil price environment since the early 1980s. West Texas Intermediate crude oil was $26.69-31.95/bbl on an average quarterly basis from first quarter 2000 through third quarter 2001, according to Cambridge Energy Research Associates, Cambridge, Mass. That was the highest average price range for such a long span since 1985, and it came from a recent historic low: The price of Arab light crude had rocketed 117% to 2000 from $12.30/bbl in 1998.

OPEC´s success faltered with a slowing economy in third quarter 2001. The group was mulling yet another price-bolstering production quota accord when the Sept. 11 attacks sent a slumping market into full collapse. Sensitivity to a post-Sept. 11 reaction to another engineered boost in oil prices led OPEC to defer further action on output cuts.

OPEC, non-OPEC standoff

It was the downward spiral of oil prices after OPEC´s deferral of action that led the group to begin considering the loss of market share to non-OPEC exporters as having evolved from irritant into threat. (The irony here is that it was a non-OPEC exporter, Mexico, that helped Saudi Arabia and Venezuela overcome their feud 3 years ago and pave the way for OPEC´s future cohesion.)

OPEC´s gauntlet-tossing over the conditional non-OPEC cuts squarely targeted Russia, and with good reason. Russia has accounted for over half of non-OPEC production growth the past few years, with net oil exports projected to climb by as much as 1 million b/d this year from levels seen 5 years ago, according to Eugene Khartukov, general director of the Moscow-based International Center for Petroleum Business Studies. Khartukov forecast Russian oil production at 7.2-7.3 million b/d and exports at 3.4-3.5 million b/d in 2002. In 1997, those levels were 6.17 million b/d and 2.39 million b/d, respectively, Khartukov estimated.

Markets have taken a hopeful sign in the sight of Moscow relenting from its initial opposition to cooperating with OPEC on output cuts. But how substantive are those cuts? Frederick Leuffer, an analyst with investment banker Bear Stearns, remains skeptical that the pledged non-OPEC cuts will materialize.

The Russian offer of a cut in exports might seem a bit disingenuous in Leuffer´s view. He notes in a recent research note that Russian oil exports typically decline in winter because of higher seasonal demand and weather-related infrastructure problems in the former Soviet Union: "Russia is unlikely to reduce oil production for several reasons having to do with production costs that are well below the current oil price; sunk costs to bring on higher volumes; distrust for OPEC, which has not been compliant with its own production quotas; and Russia´s own history of not cooperating with OPEC."

Leuffer contends that the only way for OPEC to regain oil market share is for it to allow oil prices to fall to the mid-teens or lower.

"OPEC may be using Russia as a scapegoat to create a reason to lower oil prices," Leuffer said in the Dec. 6 note. "While we believe oil prices are in middle ground and the near-term outlook for prices is difficult to call, we believe oil prices are likely to retreat further over the next 3-6 months."

Calgary-based Canadian Energy Research Institute paints a similar picture, focusing on Saudi Arabia serving as engineer of another price war, as it did in 1985-86. But CERI, which forecasts WTI at an average $18.50/bbl in 2002, contends the new market share war may not be as short-lived as those in 1985-86 and 1998-99: "Low prices and high production levels are in Saudi Arabia´s interests. Relatively high prices over the past few years could provide it with the relatively smooth transition it needs to move to a more sustained low-price strategy."

But this view runs counter to the evidence that Saudi Arabia was one of the principal architects of the price-band strategy and to the widely held perception that the kingdom would not let oil prices fall far enough to force it drain its cash reserves rather than cut budgets.

Then there is the economic fallout on Russia itself. Merrill Lynch, in a late November research note, foresaw Russian producers´ resolve crumbling under government pressure. It noted that the oil and gas industry accounts for half of Russia´s export and tax revenues; a $1/ bbl change in oil prices has an effect of $1.5 billion on the Russian budget.

Other OPEC competition

OPEC has cause for concern from other oil supply sources eating into its market share: burgeoning output growth from the Caspian region and deepwater fields, a boom in volumes of (quota-exempt) Venezuelan and Canadian syncrude from oil sands and extra-heavy crude, and new liquids output associated with increased gas production and the emerging gas-to-liquids technology.

And then there is the boom in technology advances and new structural efficiencies that have underlain a new foundation for the economics of many hitherto uneconomic prospects.

"The rise in upstream costs since 1996 is already being reversed [because of technological progress]," said CERA Pres. Joseph Stanislaw. "Upstream costs in non-OPEC countries are expected to fall by an average of 3%/year to 2010 -from almost $9/bbl to little more than $7 [in inflation-adjusted terms.

"Cost reductions will occur fastest in the deep water…at an average of 4%/year."

It soon becomes apparent that only a return to robust oil demand growth will prevent the kind of market share erosion that forces OPEC to instigate another price war.

There is certainly adequate scope for such a demand projection, especially as the developing nations´ economies continue to grow in the next 2 decades.

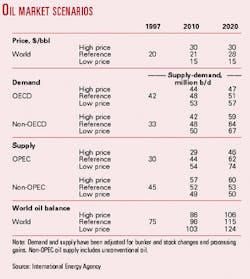

The International Energy Agency projects oil demand will climb by 41-65% by 2020 from 1997 levels, depending on the oil price scenario. But those same oil price scenarios incorporate a projection of OPEC market share that could range from 43% to 60% (see table).

Past evidence suggests OPEC will not cede that market share lightly. With the clout inherent in possessing the lion´s share of the world´s oil reserves and nearly all of its spare productive capacity, the inescapable conclusion is a moderate long-term oil price forecast at best.

Geopolitical turmoil

The near term provides a much more volatile outlook, and projections of price collapse must share the spotlight with the possibility of a price spike in 2002.

The focus of concern here is the always unpredictable regime of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. The growing ties between the US and Russia in the wake of the Sept. 11 events came to a head with an agreement last month to allow unchallenged a rollover of the latest United Nations-brokered oil-for-aid sales program in Iraq.

Whatever political expedience that accord served in light of the Afghanis- tan campaign and restive Islamic populations, it also set the stage 6 months from now for a bid by the US to renew its demand that Baghdad allow UN military inspectors back into the country. If Russia´s overtures to the US and Europe are genuine, then a confrontation with Iraq seems inevitable.

The loss of 2 million b/d or so of Iraqi oil exports would jump oil prices sharply at first, but there remains more than enough spare capacity in Saudi Arabia alone to take up the slack. The bigger concern remains a spillover effect that could affect other Persian Gulf exporters, notably a terrorist act or some widespread civil unrest and related political or military response.

The region will remain a cauldron of trouble irrespective of what happens with the Afghanistan campaign, Iraq, or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict this year. And there are some who believe that there is a shrinking capability even among the main Persian Gulf exporters to meet future oil demand (see the lead article in this week´s General Interest section). This view holds that these two concurrent trends will eventually converge in an explosion of sustained high oil prices.

If there is one certainty about the outlook for oil markets, it is a reaffirmation of the view that geopolitical considerations, for the moment, are still as much a short-term driver of oil supply, demand, and prices as are economic considerations.

The post-Sept. 11 "new world order" may be changing all that, and someday oil markets may be ruled by economic sanity to everyone´s benefit. But between here and there lies a minefield of volatility.

Near-term US gas outlook bleak; longer-term improved but volatile

null

While the near-term outlook for US natural gas prices may be bleak-absent any sustained weather-related rescue-the underlying supply-demand fundamentals of the market suggest upward pressure on gas prices in the longer term.

The combination of depressed industrial demand for gas and a strong supply response spawned by last year´s price spike has whelped a monster year-to-year storage surplus. At yearend 2001 this surplus was projected at 1 tcf by the end of the heating season on Apr. 1. That overhang would augur ill for the summer cooling season and, consequently, for gas prices for the rest of 2002-provided US wellhead deliverability were to hold up.

But there are signs that the 2001 gas supply response will prove short-lived, possibly evaporating even before economic recovery rejuvenates demand. So the wild price rollercoaster of 2000-01 could repeat in 2002-03-and perhaps for years to come.

Ephemeral supply response

US marketed gas production through the first 3 quarters of 2001 logged a 1.2% increase over the same period a year ago.

That situation is the flip side of lagging production in preceding years when gas prices were low. The resulting supply side slide coupled with rising demand created the tight markets that kept gas prices buoyed at record highs in late 2000 and early 2001.

The supply jump clearly reflected producers taking advantage of higher prices to drill more wells and reap the benefits of a spike in cash flow. But how sustained has that effort been?

Houston-based consultants and investment bankers Simmons & Co., in a late fourth quarter 2001 analysis, claimed that the 2000-01 production bump was not a "quality" supply increase.

Looking at a sample group of US producers representing over half of US gas deliverability, Simmons noted that their third quarter 2001 US production was flat compared with the prior year and down 1.7% compared with the prior quarter.

What makes this observation noteworthy is the fact that this suppy response followed a record level of gas-directed drilling activity-topping 1,000 rigs early in the year.

"…We believe as many as 200 of the last 350 rigs added since second quarter 2000 have been dedicated to acceleration projects, i.e, shallower, quick-hit wells designed to capture the opportunity presented by high commodity prices," Simmons said at the end of November.

These opportunistic efforts, especially in key areas such as East Texas, often were 10,000-15,000 ft prospects that targeted reserves of as little as 2-3 bcf/well, with initial production potential of less than 5 MMcfd and first-year decline rates in excess of 50%, according to Simmons.

And, conversely, the unexpected decline in gas prices produced an equally abrupt falloff in drilling activity.

"The recent downtick in gas-directed drilling with relatively firm gas prices is confirming evidence that wells were being drilled assuming $4.00+/Mcf."

With those price expectations already beginning to fade by the third quarter, the gas-dominated US active rig count was well into a slump by yearend 2001. Simmons projected the gas rig count would trough at 650 in first quarter 2002.

The resulting upward blip in output spawned by the price-opportunity shallow wells has briefly masked the longer-term trend of declining wellhead deliverability in the US. According to the US Energy Information Administration, more than 30% of US gas production in recent years has flowed from wells that are no more than 2 years old. So comparatively more wells are being drilled to replace the production from older wells.

It follows then that a return to historic drilling levels portends a renewal of the declining trend in US gas production in 2002.

Demand side rebound

On the US gas demand side, however, signs point to a recovery in 2002.

How much of a recovery depends on the extent of economic recovery and weather-related demand surges in the winter and summer.

The heating season has been pretty much a bust so far. EIA in early November 2001 estimated heating demand for gas this winter to be about 7% below last winter´s levels, with most of the difference concentrated in fourth quarter 2001.

Assuming normal temperature ranges in the summer leads to expectations of a surge in the cooling load in summer 2002 compared with the cool weather last summer.

Another factor is the pricing of crude oil relative to natural gas. An oil price collapse will make it tougher for the gas sector to recover from the flurry of fuel-switching that high gas prices triggered in 2001.

There are already early indications of a recovery in industrial demand for gas. According to Boston-based consultants Energy Security Analysis Inc., gas prices hovering near $3/MMbtu for several months were sufficient stimulus for chemical and fertilizer companies to reopen shutin capacity. But full recovery has been delayed by the recession. If the recession is short-lived, ESAI expects industrial gas demand to return to pre-2000 levels by yearend 2002-or about 16.5 bcfd.

Meanwhile, ESAI estimates that new gas-fired power capacity will represent an incremental pull on demand of 1.7 bcfd in 2002 and 4.6 bcfd in 2003-or year-to-year increases of 9.5% and 25.7%, respectively. Perhaps as much as 25% of that power capacity increment slated for 2003 could be delayed, however.

So what will meet this resurgent gas demand?

There remain some pipeline capacity constraints as far as US imports of Canadian gas are concerned, as well as infrastructure constraints within the US itself. And prospects for greatly expanded imports of LNG or deliveries of arctic gas from Alaska are still long-term opportunities.

Until those latter opportunities materialize-and gas persisting at $2/Mcf for long makes that problematic-rising US gas demand will be met by a short-term supply response spawned by price-sensitive, opportunistic drilling in the Lower 48.

As a result, US gas markets will see shorter, more volatile price cycles for the greater part of the decade.