Industry faces reorientation at start of 2002

Together, oil prices that slumped instead of jumped and an antiglobalization movement stymied by events demonstrate the burgeoning influence of global interdependency. Adjusting to that influence challenges the oil and gas industry this year and will do so for many years to come.

The year 2002 will be one of reorientation for the oil and gas industry. It won´t be new-economy reorientation wrought by dot-com whiz-kids peddling digital "solutions" to hidden problems. It will be reorientation of the industry´s sense of purpose. And it began Sept. 11, 2001.

Ever since terrorists destroyed the World Trade Center in New York and damaged the Pentagon in Washington, DC, killing more than 3,000 people, two crucial nonevents have thundered with scant notice through petroleum commerce and politics. One of them has to do with oil prices, which didn´t leap. The other is a new round of negotiations on international trade, which didn´t succumb to either terrorist threat or antiglobalist protest.

Together, oil prices that slumped instead of jumped and an antiglobalization movement stymied by events demonstrate the burgeoning influence of global interdependency. Adjusting to that influence challenges the oil and gas industry this year and will do so for many years to come.

New price behavior

Recent behavior of oil prices shows how interdependency has changed market responses.

Prices are supposed to rise in a crisis, especially one involving Islam and the Middle East. At least that´s what analysts, traders, politicians, and industry leaders once thought they should do. In the traditional crisis scenario, surprising events with potential to affect oil distribution always make prices spurt by inspiring panic over security of supply. Any threat thus inspires hoarding, which aggravates the price response.

It happened in 1973-74. It happened in 1978-79.

It did not happen after Sept. 11.

After the terrorist crisis there was little panic buying for storage. Buyers acted as buyers do when markets recede: They bought less. Sellers kept selling to the extent possible. Leading exporters spent November and December trying to coordinate production cuts. And prices continued the downward drift they had begun before Sept. 11. What´s more, buying and selling persevered with relative normalcy even with violence escalating in Israel and Palestinian territories and with strains exposed in relations between Saudi Arabia and the US.

So where´s the panic? What happened to the crisis scenario under which the price of crude should now exceed $30/bbl?

It smashed against global interdependency. More so than was the case in the 1970s and early 1980s, sellers need to sell as intensely as buyers need to buy. And a market vastly more liquid and transparent than it was in earlier crises makes trade more flexible and embargos much easier to skirt.

While security of supply is as important as ever, therefore, it now comes mainly from the interdependency of buyers and sellers at work in a fluid market. That most oil traders understand this explains why crude prices didn´t zoom after the terrorist attacks in the US and Israeli-Palestinian upheavals. The potential for disruption and panic still exists, to be sure. But the ability of interdependency to dissipate panic over supply upsets has proven again-as it did after Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990-to be an important dimension of the modern oil market.

Trade round

Global interdependency asserted its influence just as strongly in the restoration of trade negotiations at the World Trade Organization´s ministerial meeting in Doha during mid-November. The outcome reflected a dramatic swing in the international political mood.

Before Sept. 11, trade liberalization was under siege. With violent protests, antiglobalists disrupted and contributed to failure of a November 1999 WTO meeting in Seattle, eliciting a conciliatory hint of support from then-US President Bill Clinton.

A worldwide series of protests followed, and media attention to the concerns of antiglobalists-among them environmentalism, economic inequality, trade´s effects on cultures and economies, and the influence of international corporations-increased. In a sign of growing influence, the promise of antiglobalist disruption forced the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to foreshorten their annual joint meeting scheduled shortly after the attacks in New York and Washington, DC.

After Sept. 11, however, popular sympathy for extremist causes vanished. Recognizing a public-relations crisis, most leaders within the loose antiglobalization network that had organized protests around the world since Seattle decided to moderate their tactics. Deflated opposition probably helped trade-minded negotiators in Doha resolve disputes over agriculture subsidies, intellectual property, and labor and environmental standards in order to start a new round of trade talks.

Whatever the future holds for the antiglobalists, their success in the 2 years between Seattle and Doha forced supporters of liberalized trade to refresh their arguments and-what is especially important-to address head-on the charge that international commerce does more harm than good to the world´s poor.

"The multilateral trading system works," declared WTO Director-General Mike Moore in an Oct. 9 speech in Paris. "The last 50 years has seen unparalleled prosperity and growth, and more has been done to address poverty in these last 50 years than in the previous 500." During that period, total exports of goods and services as a share of global gross domestic product increased to 30% from 8%.

Moore cited a study estimating that developing countries would gain $155 billion/year from further trade liberalization, far more than the $43 billion/year they receive from foreign aid. A separate study, from the University of Michigan, estimates that cutting trade barriers in agriculture by one-third would increase the worldwide economy by $613 billion.

"That is equivalent to adding an economy the size of Canada to the world economy," Moore said. Eliminating trade barriers, he added, would boost the global economy by $1.9 trillion: the equivalent of two Chinas.

For the oil and gas industry, growth stimulated by trade means bigger markets. A larger global economy means greater worldwide demand for energy, including oil and gas. So industry leaders support trade liberalization. Many of them have spoken out strongly on the subject in response to the antiglobalization movement. Some of their arguments even include an uncharacteristic appeal to values beyond markets, economics, and the operational technicalities that usually absorb industry professionals.

"The system of multilateral trade needs to be defended more strongly than ever," declared Peter Sutherland, nonexecutive chairman of BP PLC at the World Energy Congress last October in Buenos Aires (OGJ, Nov. 5, 2001, p. 20). Asserting that the energy industry has a moral obligation to defend growth in trade and the energy use essential to economic development, he said, "There is more than just business interests at stake."

Earlier in the year, ExxonMobil Corp. Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Lee Raymond, in a speech to a business group in Chicago, disputed antiglobalist charges and said, "We hold the moral and economic high ground, and we must take the time and make the effort to persuade those who do not agree."

He said economic data clearly show "that if we are going to bring the greatest economic good to the greatest number of people, we must embrace open markets and international trade and investment."

Appeals to morality and interests beyond business are unusual in the low-wake speeches oil executives tend to favor. A look at global population trends shows why some of them are talking this way.

Population growth

Simply put, the population will grow by one-third in the next 25 years, and nearly all the growth will occur outside the developed world.

At present, according to the World Bank, there are 6 billion people in the world. Half of them subsist in technical poverty, meaning they live on less than $2/day. And 1.2 billion people live in extreme poverty, surviving on half that amount.

Of the 2-billion-person population gain likely in the next quarter-century, all but 50 million will occur in developing countries and those with economies in transition away from centralized ownership. Will people in that increment suffer poverty or enjoy prosperity? The answer will affect everyone.

James D. Wolfensohn, president of the World Bank Group, described the developing dynamic as "an issue of the planetary bargain" to a group in Australia last August.

"It is not going to be possible for Australians or Americans or the British or anybody to think that you can just live behind a wall," he said. "It might be possible for people of my generation and for some of you, but one thing is certain: It is not true for your kids.

"They will grow up in a wholly different world-a world in which the developing world, and the transition economy, will become dominant in size and the features of which will determine the stability of the planet."

In a statement at the beginning of the WTO meeting in Doha, the World Bank chief again emphasized the links between population growth, poverty, and stability and related them to terrorism.

"Never before have growth and poverty reduction had such tremendous implications for the stability and peace of our world as they do today," Wolfensohn said. "The tragic events of Sept. 11 and the fallout since have made it clear that we live in a highly interconnected world and that problems in one region can destabilize the welfare and security of all.

"Trade is not only, in my view, a mainspring of development but ultimately of international peace and solidarity as well."

As Sutherland said, more than business interests are at stake in these issues.

Energy at center

At the center of the stability question Wolfensohn raises about population growth in a "highly interconnected world" is energy, especially oil and gas.

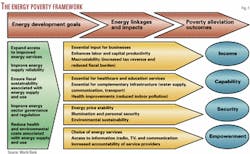

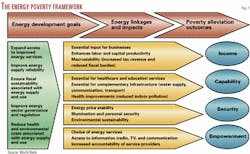

The remedy for poverty is economic growth, which requires energy. A draft chapter in World Bank´s Poverty Reduction Strategy Sourcebook relates energy development goals to poverty reduction and divides relief into four categories: income, capability, security, and empowerment (Fig. 1).

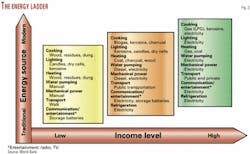

The same document provides an important reminder of the obvious but easily forgotten insight that patterns of energy use vary over a range of income. The poorest people rely on manual and animal work, combustion of wood and wastes, and batteries. The richest people rely on distributed electricity and hydrocarbons. As economic growth alleviates poverty, consumption patterns move up the "energy ladder" depicted in Fig. 2, inclining consumption in successful developing countries toward oil, gas, and electricity. As trade liberalization stimulates growth, this shift in patterns of energy use accelerates.

The trend won´t weaken from efforts to limit use of fossil energy out of concern for climate change. Those efforts will surely affect consumption-but mostly in the developed world. They won´t erode the basis for rising demand for oil and gas in the next couple of decades: the need to resist poverty in a developing world destined for major population growth.

There´s an important change here. In the past, the basis for growth in oil and gas demand was the developed world, where policy priorities tended to be military defense of the geography and processes of industrialization. Stability was a regional proposition.

Now, the basis for oil and gas demand growth has moved to a developing world destined for large gains in population and energy use. And stability, as everyone saw last Sept. 11, is a global concern. Security everywhere is a growing function of planetary stability. And stability depends greatly on economic development and ready access of burgeoning populations to the fuels of prosperity.

Creating wealth

And that´s just the consumption story. Wealth generated by development of oil and gas resources can relieve poverty in countries lucky enough to have hydrocarbon endowments. International oil and gas companies know well, however, that benefits too frequently don´t reach the people who need them most.

Companies once excluded themselves from the internal affairs of countries in which they worked; many now seek a new approach. They are at least examining reasons for the failure of resource development in some countries to improve conditions of the poor. Prominent among those reasons are corruption, inadequacy of legal systems, and deficiency of infrastructure-all of which are receiving new attention from oil and gas companies.

Even where it is easy to see why wealth from resource exploitation eludes the people who need it, however, what companies can or should do about the problem is seldom clear. This dilemma will challenge the industry for many years.

As Wolfensohn of the World Bank said about developed countries, companies working outside their home countries no longer can wall themselves off from populations affected by their operations. The connections of an interdependent world won´t allow it.

Essential purposes

These are the forces, the many dimensions of global interdependency, that are reorienting the oil and gas industry. They raise new complexities. But they also give the industry a powerful new way to respond to resistance to its work.

In an older, less interdependent world, the essential purpose of oil and gas was to fuel war machines. In the modern, increasingly interdependent world, the essential purpose of oil and gas is to feed people.