E&D organizations face structure, focus, cost issues

The structure and business orientation of exploration organizations promises to be a key issue for the exploration and development sector in 2002.

Team concepts and the application of global knowledge to local geologic opportunities are taking hold in some companies in unprecedented ways.

Despite the opening of large, previously closed areas of the world to exploration in the 1990s, much prospective acreage remains off-limits, especially in and off the US.

Drilling and completion costs have been at historic high levels in recent years and are difficult to predict even a year ahead due to uncertainties about oil and gas prices and consolidation in the service and supply industry.

Salaries for geoscience personnel increased last year and are uncertain with respect to the year just begun for the same reasons.

World oil and gas reserves have grown during the past decade, and research suggests that twice the volume remains to be discovered as has been produced.

Understand the unexpected

Some exploration organizations are changing focus and structure as they hone application of basic geologic principles and react to improvements in technology.

Materiality, capital efficiency, and value creation are common factors that differentiate best-in-class explorers from the pack, said Andrew Wood, head of global exploration, Shell International E&P BV. Wood listed key enablers for each category (Table 1).

"Trying to work on too many different plays in too many different countries is only likely to result in doing nothing properly," Wood said. "Put another way, it is no good being in all the right basins but not in the right blocks."

Focusing on the right aspects is also key, he said. The South Oman salt basin is an example of a basin "that you know has got what it takes to deliver success year after year" and which has an apparently endless capacity to surprise, Wood noted.

Light oil recently began flowing from Late Precambrian overpressured, highly porous and fine-grained siliceous deposits trapped in salt domes 4 km deep.

"A postage-stamp approach to exploration is unlikely to generate discoveries of this kind, which we owe a great deal to understanding how such a basin, with an incomparably long petroleum geological history, works. Yet so often this all-important part of the puzzle is skipped as attention becomes focused at the prospect level," Wood said.

Finding the more elusive accumulations will not be just a matter of using better tools but of going back to building on geological acumen and geological reasoning to help unlock the unseen, understanding the unexpected, and, crucially, to assess the risks involved, Wood told an interviewer for Shell´s publication "Changes."

Teams and large fields

Other ideas for exploration company structure and profitability are on the horizon.

Statoil ASA was to have set up a new global exploration unit (GEX) by Jan. 1, 2002.

GEX, made up of around 100 geologists, is responsible for accessing and proving new high potential acreage worldwide based on the best possible use of the group´s exploration resources, Statoil said.

The organization´s focus and structure reflect a high degree of integration at Statoil.

"The new organization model will allow us to focus even better on exploration and enhanced oil recovery in our core areas and awarded areas on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS)," said Henrick Carlsen, executive vice-president for Norwegian exploration and production.

The exploration team will be organized by projects. Initially the projects will be the 17th round, the Barents Sea except the Tromso Patch core area, global and regional screening, Venezuela, Kazakhstan, Iran, and Brazil.

Around 100 exploration geologists will remain within the various areas on the NCS to maximize focus on EOR in core areas and develop the best solutions for awarded areas.

"Statoil has a very experienced team of geo-personnel. By bringing the various teams together in one organization, we will lay the basis for increased efficiency and enhanced creativity," said Richard Hubbard, executive vice-president for International Exploration & Production (INT). Hubbard took the position 14 months ago.

Statoil established the new exploration unit on the basis of recommendations by a working group that consisted of representatives from its Norwegian E&P, INT, and technology divisions. GEX will report to E&P INT.

Hubbard said, "Our targets in the exploration area are very ambitious. Consequently, we have to create an organization where we as a group make the most out of our total expertise. Thus our exploration personnel will work as an integrated team, regardless of whether they are evaluating the [NCS] or areas elsewhere."

Meanwhile, separating exploration and production functions into distinct entities might be needed to lure investors that no longer view upstream operations as a growth business, a London investment banker said last month.

Such exploration companies would find and then quickly sell new reserves to production firms or royalty trusts that would extract and monetize them, Malcolm Butler, HSBC Investment Bank PLC, told the annual energy industry symposium sponsored by Arthur Andersen LLP in Houston Dec. 5.

Access to opportunities

Some say that to be profitable, a discovery outside the US must contain reserves of as much as seven times the size of one made in the US.

This would appear to be a strong incentive to explore in the US, but first one has to have access to the acreage that contains the prospects.

The restrictions seem endless: Offshore Alaska, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, the waters off California, the George´s Bank off Massachusetts and Maine, basins off the Carolinas, the eastern Gulf of Mexico, and even parts of onshore basins in the Lower 48.

Environmental groups maintain that the industry has wide access to federal lands and restricted areas, but close-up studies support the contrary.

One example involved tract-by-tract studies by a team from the US departments of Energy, the Interior, and Agriculture. The team spent 7 months studying federal lands in the Greater Green River basin of Wyoming and Colorado. It reported its findings to the National Petroleum Council, advisory body to the US Interior Department.

One finding: 68% of Green River´s technically recoverable gas resource is either closed to development or under significant access restrictions. These areas harbor as much as 79 tcf of gas. Another finding: 30% of the area is completely off-limits, and a further 39% is available but subject to restrictions industry considers objectionable.

Fortunately, the trend in the rest of the world has been to greater access to acreage.

Vast prospective basins in the former Soviet bloc are but one example. For the truly risk-oblivious company, exploration and development opportunities are available even in such corners as North Korea, Libya, Cuba, and Chechnya, among others.

Burgeoning E&D costs

Overall exploration and development costs appear to be at some of history´s highest levels.

These costs, which apply to the US and its waters, at $19.3 billion in 2000 were 29.6% higher than in 1999, the American Petroleum Institute´s annual Joint Association Survey on Drilling Costs showed. API said the industry spent 15.2% less to drill and equip US wells in 1999 than in 1998, but that followed 4 years of cost increases in 1995-98.

The higher oil and gas prices and demand that spurred increases in the number of wells drilled and in drilling and completion costs in 2000 moderated near yearend 2001, muddying the drilling cost outlook for 2002.

API also attributed the 2000 cost increase to continued economic growth, closer-to-normal weather, and the end of the previous 2-year industrywide structural reorganization.

Several trends are apparent. Gas well drilling exceeded oil well drilling for the 13th year.

API reported an overall emphasis on onshore development objectives at all depth ranges. This fueled some of the highest averages for cost per well and cost per foot ever, API said.

Significantly, operators spent $7.1 billion offshore. Industry drilled 13% more wells offshore than in 1999, and they cost 7% more on average.

Exploratory well costs

Close readers of the survey might have noticed that the dry hole cost for the 3,738 dry holes averaged $1.075 million. This compared with $593,387 for a completed oil well, $756,939 for a completed oil well, and $754,567 for all 25,620 wells.

API attributed this to offshore drilling and especially to exploratory dry holes offshore. For most of the 1990s the average cost per dry hole was higher than the average completed oil well cost, and by 1998 it was higher than the average completed gas well cost as well and has remained higher, API said.

The average footage drilled in all dry holes began to take off in 1996, and since 1997 the cost of offshore exploratory dry holes has risen steadily to $10 million/well in 2000 from an initial $7 million.

In 2000 the number of expensive sidetracks in exploratory offshore dry holes was three times larger than for exploratory offshore oil and gas completions.

Geoscience salaries

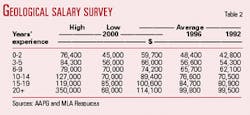

Interesting trends in the pay and demand for geologists can be seen in an annual salary survey conducted for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists.

The 2000-01 survey showed an overall 7.18% increase in salaries registered for the year. Salaries in individual experience categories climbed 5.6-10.2% (Table 2).

The survey is based on information from employed, salaried geoscientists. It excludes other income and benefits such as consulting fees, retainers, overrides, automobiles, and other perquisites. It also excludes remuneration of consultants.

Salaries firmed up as oil and gas prices strengthened from the weak levels of 1998-99.

Company mergers and downsizing in the last decade have trimmed the ranks of geoscientists in both the most experienced and least experienced categories.

One finding of the most recent survey is that more than two thirds of working geoscientists have more than 20 years´ experience.

Other findings involved bright prospects for younger hires. The pay of a geologist with 2 years or less experience climbed more than 10% from the previous survey. Responses indicated that signing incentives such as cash, stock options, and retention bonuses were becoming common.

Companies in some cases are paying new, less experienced hands higher salaries than geologists of longer tenure. That treatment inspires the more seasoned folks to seek work elsewhere.

An unemployed geologist should focus his or her skills, exhibit interpretive and thought-process skills, and be capable of working in a team environment, the survey found.

Exploration´s payoff

So how is exploration going these days?

World gas reserves have grown 1.9%/year during the past decade compared with 0.2%/year for oil reserves, two authors from Institut Français du Petròle pointed out.

The gas gains were the result of a string of gas discoveries and better assessment of existing fields.

Bernard Duval and Marie-Francoise Chabrelie said it is estimated that additional gas resources representing twice as much as current proved reserves are likely yet to be found, implying no resource constraint in the medium to long term.

They also summarized key ingredients of exploration success: early recognition of attractive geology, fast action on permitting, advanced technology to determine the best well locations, efficient drilling, and access to hydrocarbons transportation.

The structure and business orientation of exploration organizations promises to be a key issue for the exploration and development sector in 2002. Team concepts and the application of global knowledge to local geologic opportunities are taking hold in some companies in unprecedented ways.