Condensate trade will reshape crude, gas markets East of Suez

Al Troner

Asia Pacific Energy Consulting

Houston

Segregated condensate volumes produced east of the Suez Canal ("East of Suez") will only continue to grow in the near term, particularly among Mideast gulf countries and will reshape crude, oil product, and gas markets throughout the East of Suez region.

Yet condensate has impacts even further afield. Its production assists difficult gas development, quickly increases naphtha and gasoline supply, and—because it requires (unlike LPG) no specialized infrastructure—has become a major addition to crude output in East of Suez markets.

In gas development, condensate production has become a key consideration in launching new developments, providing additional project revenue as well as revenue when developers are still spending to complete the gas supply chain. In some oil-producing countries of the region, condensate has become a major part of liquids output.

Condensate usually yields more than half naphtha in simple distillation but affects gasoline markets as well as petrochemical feedstock needs. In addition, since the onset of the Great Recession in 2008, its influence has only grown.

While condensate has a wide range of utilization, its supply is increasingly shaped by petrochemical markets and more particularly petrochemical prices. The divergence of oil and petrochemical markets was most notable in Asia-Pacific, as the region began to climb out of recession in second-half 2008 through 2010. We expect that condensate prices will remain loosely aligned with general crude prices, but there will be more occasions when they follow the direction of petrochemical markets.

Condensate is not crude, however, but a crude equivalent and a by-product of gas production. Its supply economics are therefore based on gas output. As a by-product, production volumes reflect gas output, which leads to a certain element of price inelasticity in condensate sales. While condensate can be considered a light sweet crude equivalent, it has diverged substantially from crude pricing since 2008.

There are times when condensate prices are simply dictated by the invariability of incremental condensate output as a function of gas production. When storage tanks are full, condensate must be sold at whatever price is obtainable. Unlike crude production, it is not easy to throttle back the engine. The invariability of condensate supply—despite shifting demand—creates marketing, trade, and pricing anomalies, not only in petrochemical feedstock and gasoline markets, but also in crude balances.

Accelerated development

The buildup in condensate production for East of Suez markets has sprung from a structural shift in the region from considering gas a poor second to finding oil, to an independent focus for hydrocarbon development. Accelerated development has been the norm for gas finds since 2000. In both the Mideast gulf and Asia Pacific, recession has slowed the buildup in gas output and parallel segregated condensate production, but not reversed it.

It is inevitable that increased gas production will underpin a parallel and, for East of Suez markets, unprecedented rise in condensate production. For a gas developer the choices are simple: With all other factors being equal, the decision is a matter of simple choice, yes or no. Clean gas gets developed before dirty; onshore gas finds, before offshore; wet gas, before dry.

| . |

East of Suez condensate studyOGJ readers can find the full report "Condensate East of Suez 2011: NGL Impacts on the Light Ends Balance," Asia Pacific Energy Consulting, Houston, at http://ogjresearch.stores.yahoo.net/condensate-east-of-the-suez.html or by going to www.pennenergyresearch.com and entering "Condensate" in the search box. |

A buildup of gas production will underpin a sustained rise in condensate output. Transporting gas easily requires NGL content to be reduced to minimal levels; otherwise flow will puddle in pipelines and destabilize LNG cargoes. For gas transportation, NGLs must be for the most part removed; this processing will support increased condensate production, particularly in the Mideast, for years to come.

A further incentive to development of condensate production exists for members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Condensate remains outside of national production quotas, and gas development, in a small-volume oil exporter such as Qatar, allows for massive earnings from condensate sales and will soon exceed black oil sales.

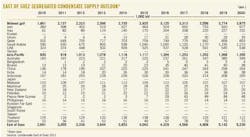

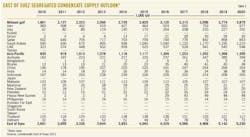

Table 1 presents condensate production by countries East of Suez.

The Mideast gulf has remained the focal point of incremental condensate production. By 2015, Saudi Arabia will increase segregated condensate output by two-thirds; Qatar will top 700,000 b/d; and Iraq, a small-volume producer in 2011, should approach 200,000 b/d for segregated production. The odd man out has been Iran, with project work slowing to a near standstill. This country will see condensate production rise only modestly, despite great hopes pinned on further South Pars phases.

Together these three countries will produce more than 2.1 million b/d of segregated output by 2016.

Despite Iran's gas development woes, the Mideast gulf will increase segregated condensate production by more than 40% through 2015, topping 2.9 million b/d, and see output rise further by nearly a third by 2020 to reach nearly 3.9 million b/d. In contrast, Asia Pacific will see segregated condensate production rise far more slowly, increasing only by 63% through 2020. Yet the forecast 1.36 million b/d of segregated condensate output will have a major impact on Asia Pacific liquids production, as black oil production will decline to less than 6 million b/d by the end of the decade.

Despite attempts to restrain condensate sales abroad, segregated condensate exports will rise sharply from Saudi Arabia and Qatar and more moderately from the UAE this decade. Saudi Arabia, of course, has the option at any time of spiking all or a significant portion of its condensate exports into its enormous crude pool, but Qatar does not have that luxury. We expect that the rise in segregated condensate production will inevitably increase Mideast condensate exports.

Goldilocks Dilemma

Condensate is remaking the dynamics of upstream development across the Mideast gulf and Asia-Pacific. This NGL has finally gained recognition upstream as a vital revenue producer that allows more difficult, costly gas developments.

We expect that the structural shift to accelerated gas development will continue in East of Suez markets and inevitably will underpin a parallel, sustained rise in segregated condensate output. One of the chief concerns of the viability of Australia's coalbed methane-based LNG projects is their ability to weather sustained periods of low gas prices without condensate revenue. Many gas developers are reluctant to take that risk.

In the Mideast gulf, condensate will play an ever more important role in getting new gas projects up and running. Many Mideast gulf gas producers have run out of the easy-to-develop onshore gas prospects that characterized projects for much of the past generation. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, and Kuwait now have to undertake development of gas reserves that are difficult and costly: Offshore (Saudi Arabia), tight sands (Oman), highly dirty (Abu Dhabi), or technically challenging (Kuwait) discoveries are what these countries must depend on for incremental gas supply.

Developing this future output will be far more costly than in the past, and it is clear that highly subsidized electricity sales, together with the need to promise heavily discounted NGLs to new petrochemical plants, will keep Mideast gulf gas demand growing, whether additional gas is cheap or expensive to develop.

This leads to a pricing conundrum, in which condensate plays a pivotal role in the Goldilocks Dilemma. To develop new and more costly gas, Mideast gulf governments must allow the price of gas and accompanying NGLs to rise to cover the increased cost of converting that potential supply into actual production. Since many of the new projects are technically daunting—and far beyond the skills and experience of most Mideast gulf state companies—foreign investors, companies highly skilled in developing challenging upstream gas reserves, must be attracted and committed.

That means much higher prices for gas and NGL production, in order to pay these foreign partners, such companies as ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, and Occidental. Yet many of these same gulf states are striving to attract massive petrochemical investment, using the sweetener of supplying long-term discounted NGLs to serve as ethylene cracker feedstock. This means discounted ethane, LPG, and condensate.

The price cannot be both high and low at the same time and, since few Mideast gulf governments trust markets to set price, they now seek to set gas and NGL price levels that are "just right"—an unenviable task.

Condensate may well be the key to solving this predicament. If host countries reserve difficult-to-transport NGLs, such as ethane and LPG, for discounted feedstock sales to petrochemical investors, gas exploration and development could be supported by export sales of condensate. Yet this would mean ceding some, if not all, marketing to the gas development company, a measure that only Oman has been considering.

Product supply effects

Whole condensate generally yields more than 50% naphtha, and a fair share of that can be converted to gasoline. While it is clear that segregated condensate output will rise sharply in the medium term, many analysts have yet to realize that condensate already has reshaped light-end balances East of Suez, in particular allowing Mideast product sellers to continue naphtha sales abroad, despite the diversion of growing volumes of naphtha to domestic gasoline production.

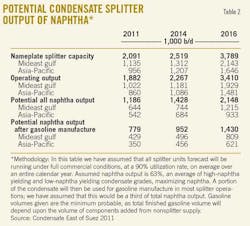

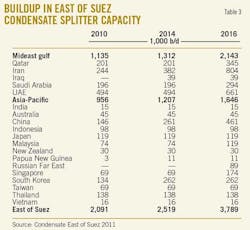

More than three quarters of reported naphtha available for export from Mideast gulf sellers in 2011 came from condensate, either condensate sold as naphtha (such as Saudi A-180) or naphtha derived from condensate splitting. By 2016, splitter capacity East of Suez will grow to nearly 3.8 million b/d and will produce about 2.15 million b/d of naphtha, nearly 1 million b/d in the Mideast gulf. Condensate will remain a vital support in continued Mideast naphtha exports and most paraffinic naphtha produced will move to Asia-Pacific (Table 2).

For markets in which the price of gasoline has been kept far too low for far too long, condensate splitters will be the key in meeting ballooning gasoline demand over this decade. Despite financial woes, intensified by sanctions, Iran will likely triple its condensate processing capacity by 2016.

While much of the splitter output will be used as petrochemical feedstock, condensate splitting will play an important role in reducing, if not fully eliminating Iran's need for gasoline imports. And, since a 200,000-b/d condensate splitter can be built at a cost of around $1.5 billion in the Mideast, while a high-conversion conventional refinery of the same size would cost more than $4-5 billion, there has been a surge in new condensate splitter proposals in 2010-11.

Yet not only are splitters cheaper, they produce far more naphtha and gasoline than a conventional, high-conversion refinery—something in the range of 60-65%, compared with a refinery's average 40-45% output.

Yet it must be underlined that a condensate splitter complex is basically a simple plant configuration to process a specialized feedstock. The tower has cut points adapted to a feedstock that yields a high proportion of light-ends, with sufficient overheads to prevent bottlenecking in distillation.

Increasingly splitter complexes have hydrotreating and reforming units, but the rule remains that splitters should be simple and relatively cheap, designed to produce large volumes of light-ends. Iran's 244,000 b/d in condensate processing capacity in 2010 was capable of producing roughly 105,000 b/d of petrochemical feedstock and about 85,000 b/d of low-quality gasoline (Table 3).

Pricing paradoxes

Since condensate yields mainly naphtha, paraffinic naphtha, N+A naphtha, and naphtha-derived gasoline are the key product determinants in assessing condensate price. In recent years, the petrochemical sector's influence on condensate prices has grown, yet other products, notably middle distillates, can also have an impact on markets valuing condensate.

A new round of construction for condensate splitters in the Mideast gulf and in both Northeast and Southeast Asia, will impact naphtha and gasoline trade flows by 2016.

It is interesting to note that condensate and crude prices have increasingly diverged. In the 2008-10 recession, condensate prices rose at least three times, supported by mini-booms for petrochemical feedstock, while overall crude prices dropped sharply yearend 2008 through early 2009 and only gradually regained strength from yearend 2009 and throughout 2010, stabilizing in 2011.

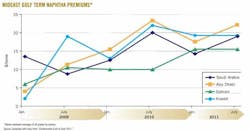

Mideast gulf naphtha exporters noted the divergence as well. While April 2009 was the nadir for Mideast gulf term naphtha prices, including condensate sold as naphtha such as Saudi Arabia's A-180 grades, naphtha prices rose sharply in second-half 2009. Prices for other gulf exporters lagged the market, including Kuwait (full-range and light plant naphtha), Qatar (Messaieed splitter-derived naphtha), and Abu Dhabi (low-sulfur naphtha, C5+—another condensate sold as naphtha—and splitter-derived naphtha) remained high even as soft markets could not absorb exports.

Prices rose by early 2010 and were confirmed in April and July term renewals by Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi. Another price slump hit exporters in early 2011, although Abu Dhabi and Kuwait increased prices by April term renewals (Fig. 1).

This leads to one of the pricing puzzles at the heart of condensate markets. While naphtha is the chief determinant of condensate price levels, crude, gasoline, and middle distillate demand also shape condensate sales. One of the chief justifications for Mideast gulf condensate splitters would be that incremental condensate output would be absorbed by these units. This would support segregated condensate prices, as there would be less volume of condensate to export.

Yet when Mideast splitters aim mainly at producing gasoline for the domestic market and paraffinic naphtha output is for the most part exported, this tends to weaken naphtha prices and eventually softens condensate prices as well. The key for future prices will be the ability of Asia-Pacific to absorb additional Mideast gulf naphtha output as well as new exports from India. Many Mideast state companies appear to be unaware of this danger.

National oil companies, both in the Mideast gulf and in Asia, appear determined to maximize their condensate opportunities. Condensate will grow in importance as Mideast producers realize that producing and processing condensate will allow them to meet ballooning domestic gasoline demand, while continuing large-volume naphtha exports. It will be the key instrument to support development of difficult gas discoveries, whether tight gas, sour gas, or costly offshore projects.

In Asia, where transport and petrochemicals are competing for the same light-end output, such as in China, condensate's dramatic impact in increasing naphtha and gasoline output has been increasingly recognized. All three national Chinese state oil companies—CNPC/Petrochina, Sinopec, and CNOOC—have built condensate splitters, and condensate is increasingly separated and segregated from overall crude production.

For international oil companies, condensate allows them entry into upstream gas development and in countries where majors and large independents have been banned from developing crude finds for decades, such as Saudi Arabia. Majors and large trading independents have found that adding condensate production and condensate processing to their activities can provide additional volumes for crude trade as well as naphtha and gasoline marketing.

Majors with substantial petrochemical production, most notably Shell, have been developing condensate processing also as a means of providing feedstock for their petrochemical plants.

After decades of being considered a specialty trade, condensate has entered the mainstream of oil and gas production, trade, and marketing. Condensate has gone from an oddity of the hydrocarbon world to occupy a small but essential piece of the products' jigsaw puzzle in the Mideast gulf and Asia-Pacific.

We see condensate trade, like LNG marketing, becoming not only a global marketing activity, but also part of an integrated global supply-demand balance.

The author

| . |

Manuscripts welcomeOil & Gas Journal welcomes for publication consideration manuscripts about exploration and development, drilling, production, pipelines, LNG, and processing (refining, petrochemicals, and gas processing). These may be highly technical in nature and appeal or they may be more analytical by way of examining oil and natural gas supply, demand, and markets. OGJ accepts exclusive articles as well as manuscripts adapted from oral and poster presentations. An Author Guide is available at www.ogj.com, click "home" then "Submit an article." Or, contact the Chief Technology Editor ([email protected]; 713/963-6230; or, fax 713/963-6282), Oil & Gas Journal, 1455 West Loop South, Suite 400, Houston TX 77027 USA. |

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com