UNCONVENTIONAL OIL & GAS FOCUS: Shell exec says shale, tight gas benefits outweigh likely risks

Shale gas and tight gas offer many countries the best chance to move toward an affordable energy supply that promises an alternative to coal-fired power generation and potentially a way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, said Royal Dutch Shell's executive director, upstream international.

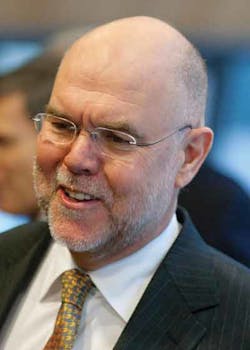

Malcolm Brinded acknowledged mounting "public anxiety" about the safety of developing and producing unconventional oil and natural gas. He spoke late last year to the Foundation for Science and Technology in London.

"Tight gas has already brought tangible environmental and economic benefits to North America," he said. "It now offers the rest of the world the opportunity to cut carbon dioxide emissions in the power sector while meeting surging demand for affordable energy.

"The sheer scale of this opportunity is what makes it so vital that any discussion about these energy sources is underpinned by hard facts and rigorous analysis," he said.

Brinded said industry has been "too hesitant to engage with the public about these matters, leaving the field clear for a number of misconceptions to take root, misconceptions that form a major part of the case against tight gas." Encouraging gas producers to maintain high operational and environmental standards, Brinded recommends governments implement "strict and well-targeted regulation" regarding shale gas and tight gas operations. Many countries are moving to develop their gas resources.

"The tight gas revolution is poised to become a global phenomenon," he said. "China, Latin America, Australia, Eastern Europe, and South Africa all hold significant tight gas deposits. Coupled with the rapid expansion of the global LNG market, this is giving more governments the confidence to back natural gas."

The International Energy Agency estimates the world will need to invest some $38 trillion to meet projected energy demand in the period to 2035 ($9.5 trillion in gas).

Shell's operating principles

Shell established operating principles for its tight gas operations worldwide to protect water, air, wildlife, and the communities in which Shell operates. These principles cover well design, construction, and operation.

"At Shell, we use what is known as a safety-case approach based on North Sea regulation. This requires our staff and contractors to assess closely and mitigate systematically all potential risks before drilling begins," he said.

"I emphasize this because a major public concern is that hydraulic fracturing could lead to the contamination of fresh water supplies, either by the fluid used to fracture the rocks, or by the gas itself."

A 2011 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that "there is no evidence" that contamination by fracturing fluids is occurring, he said.

MIT researchers noted "evidence of natural gas migration into freshwater zones in some areas, most likely as a result of substandard… practices by a few operators" in designing and constructing wells.

To put that in perspective, Brinded noted industry has used fracing more than 1.1 million times in the US during the past 60 years.

Industry is responsible to demonstrate to the general public that proper well design and construction prevent groundwater contamination.

"At Shell, we only operate wells that can be safely isolated from potable groundwater," he said. "First, where we drill through the aquifer, we line all of our tight gas wells with multiple steel and concrete barriers to prevent gas or liquids from escaping.

"Second, our North American gas formations that require fracturing are typically located a mile or more below the water table, trapped below many layers of impermeable rock. So, it is virtually impossible for gas or liquid to reach drinking water supplies through the localized cracks induced by fracturing the rock, which typically extend no more than 100 m above the well."

Displaying 1/2 Page1, 2Next>

View Article as Single page

About the Author

Paula Dittrick

Senior Staff Writer

Paula Dittrick has covered oil and gas from Houston for more than 20 years. Starting in May 2007, she developed a health, safety, and environment beat for Oil & Gas Journal. Dittrick is familiar with the industry’s financial aspects. She also monitors issues associated with carbon sequestration and renewable energy.

Dittrick joined OGJ in February 2001. Previously, she worked for Dow Jones and United Press International. She began writing about oil and gas as UPI’s West Texas bureau chief during the 1980s. She earned a Bachelor’s of Science degree in journalism from the University of Nebraska in 1974.