Government-industry engagement revitalizes UK tax regime after 'low-point' budget of 2011

Editor's note: This article is adapted from an October 2012 report from Oil & Gas UK, London.

The UK's offshore oil and gas industry has experienced nearly 2 years of unprecedented change in the fiscal regime. Various modifications to the regime have seen the balance of risk and reward shift appreciably between government and industry for different types of investment.

Submission of the national budget on Mar. 23, 2011, was a low point. Budget 2011 reaffirmed the UK oil and gas tax regime's reputation for fiscal instability—a reputation the industry had hoped was a thing of the past. The 12-percentage-point increase in the supplementary-charge rate to 32% meant that new investment was now taxed at 62%, with fields developed before 1993 taxed at up to 81% if they paid petroleum revenue tax (PRT). In addition, the tax relief on decommissioning was effectively restricted to 50% against corporation tax and supplementary charge, even though profits were taxed at a higher rate, a feature not seen in any other regime.

While these measures were intended to raise around £2.2 billion/year in tax revenues, they had a material impact on the balance of risk and reward from an investor's perspective. A quarterly index by Oil & Gas UK showed that operators' business confidence after Budget 2011 fell by 25 points on a 100 point scale, the greatest quarter-on-quarter decrease since the index began at the start of 2009, and a similar trend was felt across the supply chain.1

Broadly, the impact of the tax increase was fourfold:

• Investments in the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) became less attractive, losing up to 24% of their value. This impact was seen most markedly in commercially marginal projects which then struggled to attract investment, including a number of potentially big new-field developments as well as new investments in existing fields.

• Field allowances intended to promote investment in more marginal new fields were seen to be less effective.

• The value of new exploration in the UKCS was impaired.

• The UK was perceived by overseas investors to be a less certain destination for investment, leading to an increase in risk premiums.

Treasury adjustments

To the credit of the Treasury, the announcement of the tax increase was followed by a commitment to engage with industry on the impact of the rise and on concerns regarding decommissioning tax relief, albeit ensuring that the full tax increase remained in place. Through the tax regime, the Treasury is a key stakeholder in the UKCS. The Fiscal Forum was created by Treasury to enable ministers to engage more effectively with a wide cross section of the industry in pursuit of the joint government-industry objective of maximizing economic recovery from the UKCS.

Budget 2012 was much heralded by the government as "a budget for growth," and measures announced since then are consistent with that aim. The existing small-field allowance (SFA) was enhanced, and a new allowance was introduced to open up the West of Shetland area for large oil developments. The government also committed to find a solution to resolve the industry's uncertainty over the continued availability of decommissioning tax relief; it favored a contractual mechanism and has since carried out a detailed formal consultation. On July 25 the government introduced a new-field allowance for shallow-water gas developments, and on Sept. 7 it announced a "brown-field allowance" (BFA) to promote further productive investment in mature fields.

Falling production

The current production dynamic is worth noting. While UKCS production between 2000 and 2010 declined by around 6%/year, in 2011 it crashed by 19%. This effectively negated the previous increase in the supplementary charge, as the tax yield for 2011-12 was £2.3 billion lower than anticipated by the Treasury only months earlier, and energy imports increased with a detrimental impact on the UK's balance of payments.

This drop in production reflects the underlying challenge of operating in a mature province—sustaining production by attracting new investment to extend field life—made more difficult by a relentlessly increasing tax rate reducing the attractiveness of the province to global investors. It also reflects the costs now being encountered in extending infrastructure beyond its original design life, in part a consequence of the design constraints of the "Cost Reduction in New Era" (CRINE) initiative of the early 1990s. Current signs are that production in 2012 has again fallen by more than anticipated, reflecting unexpected, prolonged outages in several areas of the UKCS, including Elgin.

Despite the disappointing output in recent years, the UKCS is attracting historically high capital investment, more than £11 billion this year. However, this has been concentrated in a limited number of particularly attractive opportunities, mostly in new fields and one or two major field redevelopments. Less attractive, more expensive investments in new fields and in fields already in production (brown fields) have stalled due to the inability to compete effectively for capital. This has led to a "two-speed" UKCS, which does not accord with the imperative to maximize economic recovery. The measures announced since Budget 2011 should have a material benefit on the future of the UKCS.

A consideration of each of these measures follows.

Small-field allowance

Prior to Budget 2011, the SFA meant that new fields of 20 million boe or less qualified for the full £75 million worth of allowance with a taper going down to zero for fields 25 million boe in size. The announcement in Budget 2011 increased both the value of the allowance to £150 million and the qualifying criteria to 45 million boe, with a taper down to zero for fields 50 million boe in size. The increase in the SFA protects qualifying projects from downside risks such as a sudden fall in the oil price, unexpected cost increases, or low-case reserves being realized.

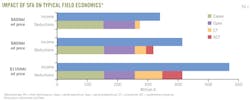

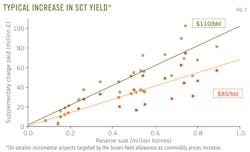

Fig. 1 demonstrates how the SFA shelters some of the profits of a small field against the 32% supplementary charge tax (SCT) at lower oil and gas prices, though the field always pays corporation tax (CT) of 30% in full measure. This effect is particularly seen in new oil fields of less than 6-8 million bbl and gas fields of less than 14-17 million boe.

Oil & Gas UK has assessed the impact of the increase in the SFA on UKCS projects using data available through the annual Activity Survey and its own set of screening criteria.2 3 The increase in the SFA has a subtle but beneficial impact on project economics: protecting downside value for the investor, providing additional support averaging at £11 million/project on a discounted basis; increasing capital efficiency (P/I)4 by an average of 0.1/project; improving internal rate of return by an average of 3%/project. The analysis shows that, based on currently known developments, the increase in the allowance attracts enough new investment that it more than pays for itself. Moreover, it will have a beneficial impact on exploration activity, which has been depressed over the last 2 years despite current oil prices.

Of 35 potential new small-field developments examined by Oil & Gas UK, five were considered to be unlikely to proceed without the increase in the SFA. Together, these five projects generate around £470 million in production tax receipts with further economic benefits arising from the capital investment required to develop these fields. In comparison, the increase in the allowance is estimated to reduce supplementary charge collected from other small-field opportunities by £400 million, demonstrating that even on existing new-field opportunities there is a net benefit to the Exchequer.

The full effect of this measure will be felt only in the longer term as it provides vital support for exploration, which had been particularly impaired by the tax increase of Budget 2011. Only 14 exploration wells were drilled in 2011, half the number drilled in 2010. While new discoveries on the UKCS vary widely in size, the median size of new fields discovered on the UKCS is around 10-15 million boe. The revised allowance is more closely attuned to typical exploration outcomes in the UKCS, effectively rebalancing risk and reward for exploration, helping to offset part of the detrimental impact of the previous year's tax increase.

Since the SFA increase in Budget 2012, a number of companies have been seen to adjust their exploration strategies as they price in the effect of the larger allowance. In part the intense interest shown by explorers in the 27th licensing round reflects this. While many factors affect exploration activity, including access to finance, availability of drilling equipment, and access to infrastructure, the increase in the SFA has certainly influenced intent.

Deepwater allowance

In Budget 2012, Treasury announced an allowance that would shelter up to £3 billion of production income from the supplementary charge for fields that meet the following criteria:

• Water depths in excess of 1,000 m (found only in the West of Shetland region).

• Minimum reserves of 25 million tonnes (approximately 188 million bbl).

• Maximum reserves of 40 million tonnes (approxiately 300 million bbl), with the allowance tapering down to zero where reserves exceed 55 million tonnes (approximately 412 million bbl).

The Rosebank project is a direct candidate for this field allowance. It had been discovered in 2004 but had always been seen as noncommercial given the fiscal framework and oil prices of the time, and the increase in the supplementary charge in 2011 had not improved matters. However, just months after the allowance was announced, the owners announced that the project had entered the front-end engineering and design stage, a move that was clearly stimulated by the new allowance. The Rosebank project alone is set to deliver an estimated 240 million bbl of recoverable reserves.

Perhaps more importantly, further potential upside arises from the infrastructure put in place for the Rosebank development. This will open up a remote frontier region, which currently lacks export routes to get hydrocarbons to market.

Shallow-water gas allowance

In July 2012, the government announced a further new-field allowance to shelter up to £500 million of income from the supplementary charge for sizable gas fields in shallow water. A specific beneficiary of the allowance was Cygnus gas field, whose owners sanctioned the project in August 2012. The development of Cygnus will boost the UK economy by:

• Injecting £1.4 billion of capital investment into the economy.

• Directly creating 1,200 new jobs in the UK.

• Recovering an estimated 18 billion cu m of gas (proved and probable reserves).

The allowances for both shallow-water gas and large deepwater projects would be available to any fields which met the designated criteria. They, like the allowances introduced in 2009 for high pressure-high temperature (HPHT) and heavy oil projects, are a way of addressing through the tax regime the high upfront capital costs required to develop such fields.

The field allowances have been calibrated to improve key economic metrics, in effect adjusting the marginal tax rate back to a level where the fields can be developed. Without these allowances, both Cygnus and Rosebank would have been trapped by the current fiscal environment. This would have prevented the recovery of at least 340 million boe of oil and gas, halting billions of pounds of investment, and preventing the UK from maximizing the economic recovery of its oil and gas resources.

Brown-field allowance

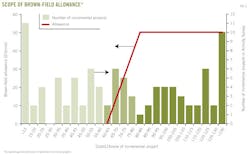

On Sept. 7, the government unveiled the BFA, which seeks to unlock marginal investment in existing fields. The BFA is unusual compared to other existing field allowances because:

• It targets fields already in production rather than new-field developments.

• The size of the allowance is determined on a sliding scale based on the capital cost per tonne of the incremental project and is not related to the physical characteristics of the field.

• A distinction is made between PRT and non-PRT fields in terms of the maximum amount of relief that can be received.

• Where the conditions for the BFA are met, the allowance is additional to rather than instead of any existing new-field allowances, provided the field has sufficient income to use both allowances.

The BFA acts in a manner similar to that of the new-field allowance but is applicable to new investment in existing fields which delivers incremental production over and above that contained in the intended field development plan. The allowance will be available for brown-field developments costing more than £80/tonne (£10.67/boe) to develop and is set at £50 of relief for every tonne of oil or gas equivalent (£6.66/boe) produced. Projects that cost £60/tonne (£8/boe) or less to develop will not get the allowance; projects that cost £60-80/tonne will earn the allowance on a pro-rata basis.

The design of the allowance, with a cap on quantum of allowance, means there is no motivation for companies to pursue more expensive development options. To secure the BFA, licensees must submit an addendum to the field development plan covering the scope of the incremental development and also provide an independent verification of the associated costs. Once the allowance is awarded, it is not intended that the allowance will be revisited in light of the post-investment outcome. The BFA is a new fiscal lever to promote investment in existing fields, effectively acknowledging that the current marginal tax rate has become a barrier to investment.

The benefits of this allowance are threefold:

• Extra barrels that would otherwise not have been produced are brought on stream, helping to slow the UKCS's decline in production. As brown-field investments typically have short lead times, this measure should rapidly help to alleviate the current production decline.

• Increased oil recovery projects and enhanced oil recovery projects may be given greater consideration, although EOR using carbon dioxide is not currently within the scope of the allowance.

• Field life is extended, a result that defers decommissioning costs and increases the window of opportunity for marginal fields in the vicinity to be tied back to existing infrastructure.

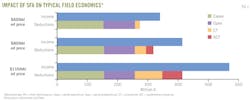

Through the annual Activity Survey, Oil & Gas UK is aware of around 100 incremental projects of which around 40 have capital development costs of £80/tonne or higher and 16 have capital development costs of £60-80/tonne. These projects are at different stages of maturity and some are not yet or may never be commercially viable, even if they were able to access the allowance. The economic benefit of the allowance is a subtle one which provides qualifying projects with a maximum net benefit of £2.10/bbl developed on an undiscounted cash basis.

Nonetheless, analysis suggests that the introduction of the BFA should in the near term lead to at least seven new investments proceeding which would not have done so without the allowance. These seven projects made commercial by the BFA should alone lead to around £2 billion of capital investment, delivering 160 million boe and contributing production tax revenues of over £2.5 billion, with two key projects accounting for over 60% of this amount.

Despite providing some downside support to the investor, the BFA still provides ample return to the Exchequer. There are 56 incremental projects identified which could possibly, over time, secure the allowance. Of these, 35 projects are likely to proceed, including a couple of very large, complex projects. If these projects do proceed, a net £5.6 billion of production tax income could be seen by Treasury (in 2011 money, undiscounted, and assuming $85/bbl oil and 50 pence/therm gas). This is a large prize compared to a potential short-term cost to the Exchequer estimated by Treasury at £100 million/year.

Analysis shows that smaller brown-field projects (say, less than 1 million tonnes) in the allowance catchment area that are likely to go ahead all pay supplementary charge and that the return to the Exchequer increases rapidly as oil and gas prices rise. Typically, the Exchequer gains a payback of 10-15 times in corporation tax and supplementary charge receipts what it affords these projects in amount of allowance. This demonstrates the potency of the BFA.

Certainty on decommissioning

The final step in the oil and gas value chain is the decommissioning of offshore fields and associated infrastructure and restoration of the seabed to its previous condition. Until now, licensees have been concerned that the tax relief available under the tax code for decommissioning could be removed before decommissioning occurred. This concern was exacerbated by the decoupling of tax rates charged on profits and relief available for (decommissioning) costs, which was announced in Budget 2011.

The government and the industry recognize that achieving certainty over decommissioning tax relief would facilitate asset trades, free up capital currently tied up in security for decommissioning, and send a positive signal to industry that the UKCS is a stable environment in which large-scale, long-term investment decisions can be made. These assertions are underpinned by a range of different sources. An examination of 16 fields which have changed ownership in the last 5 years, for example, shows investment in these assets increased by £2.1 billion, delivering an additional 300 million boe. This extended the productive lives of these assets by an average of 10 years.

Hannon Westwood studied the impact of the government's having given certainty on its current decommissioning position on the province's productive life. Conservative indications were that certainty could lead to an additional 1.7 billion boe being recovered from the UKCS over time, and decommissioning could be postponed by a further 5-7 years on average.

A 2011 study by Alexander Kemp shows the critical importance of retaining infrastructure, with estimates that up to around 950 million bbl of oil and 8 tcf (equivalent to 2.3 billion boe in total) would be lost through the premature decommissioning of existing infrastructure.5

In Budget 2012, the government announced that it would provide certainty on the continued availability of tax relief for decommissioning, and in July the Treasury launched a formal consultation on proposals to introduce a contractual mechanism to do just this.6 Reflecting the progress that has been made on this issue, the consultation document states in its introduction that "the government recognizes that a lack of certainty over how much decommissioning tax relief companies will be able to claim is currently making it difficult for assets to change hands, limiting the funds available for new ventures and deterring incremental investment. The contractual approach that the government is proposing in this consultation is intended to address these issues, facilitating ongoing investment and production in the UKCS and increasing Exchequer benefits."

The industry is wholly aligned with the government's policy objectives. The proposed solution should cost the government nothing yet provide the certainty sought by all parties. The consultation should lead to constructive measures in Finance Bill 2013 to remove fiscal uncertainty and should give a high degree of assurance to previous, current, and future investors in the UKCS that extending the life of their fields is worthwhile and make asset transfers to smaller companies easier to achieve.

Irony and change

There is a certain irony in that, had the tax increase in Budget 2011 not occurred, then the fiscal regime would not have experienced as much change as has occurred in the intervening period. The tax regime has a powerful influence on investor sentiment, and the Treasury has for the first time acquired fiscal measures which are seen to have a powerful impact on all aspects of the exploration and production business cycle.

To again quote from the recent decommissioning consultation document issued by the Treasury, there has been substantial progress over the last 21 months: "The government recognizes the considerable contribution that the UK oil and gas sector makes to the UK economy. Even as we move towards a less carbon-intensive future, oil and gas are set to remain a vital part of our energy system for years to come. The sector also has an important role to play in driving jobs and growth across the UK and is a rich source of skills, expertise, and technology. It is therefore important that we do all we can to maximize the economic recovery of our indigenous hydrocarbon reserves, and the government remains firmly committed to encouraging investment and innovation in the UK Continental Shelf. As the basin matures, the tax regime will continue to play an important role in helping us achieve those objectives."

The various tax changes have led to a more complex yet more flexible regime. With marginal tax rates remaining at up to 62-81%, depending on the field, the Exchequer is still a net winner. The increase in supplementary charge was designed to raise more than £2 billion/year, whereas the sum total of the measures announced are seen on Treasury's projections to cost a few hundred million pounds a year. Extending the field allowance mechanism into the brown-field arena has been a critical and overdue step.

The government has the levers to promote investment at all phases of a field development plan and, as such, can more directly help arrest production decline. Government and industry interests are aligned as never before. Securing certainty on the amount of tax relief available on decommissioning costs reduces a risk factor for companies, leaving the industry to focus on managing other operational risks such as those geological or technical. This will allow the UKCS to be managed as a long-term asset, not simply a source of short-term cash flow. As the government acknowledges, alongside tax revenues from production, the benefits of the UK's oil and gas industry can also be measured in terms of employment and related tax revenue, skills, and technology.

References

1. http://www.oilandgasuk.co.uk/knowledgecentre/oil_and_gas_uk_index.cfm.

2. The 2012 Activity Survey is available at http://www.oilandgasuk.co.uk/publications/viewpub.cfm?frmPubID=434.

3. Economic assumptions used throughout the analysis unless otherwise indicated: $110/bbl oil, 60 pence/therm gas, with economics typically shown at 10% real discount rate with all values adjusted to reflect 2011 money.

4. P/I refers to (P)—the net present value, post-tax—divided by the capital invested (I) and is often used as a measure to rank capital investments.

5. Kemp, A.G., Stephen, L., "Prospective Decommissioning Activity and Infrastructure Availability in the UKCS," 2011.

6. "Decommissioning Relief Deeds: increasing tax certainty for oil and gas investment in the UK Continental Shelf," July 2012.