Restricting North Dakota gas-flaring would delay oil output, impose costs

Trisha Curtis

Tyler Ware

Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc.

Washington, DC

Public concerns about flaring of natural gas have led to suggestions that the practice be prohibited in booming North Dakota even if it means permanently or temporarily halting crude oil production. An analysis by the Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc. indicates that production delays of only a few years would be very costly.

Policies on flaring must weigh prospective losses against any gains in environmental protection and saved gas. A decision to prohibit flaring would have to be based on the conclusion that the environmental benefits outweigh the economic costs of delayed oil production. However, the losses in natural gas production are not trivial and clearly justify policy strategies which shorten the time to build out natural gas infrastructure.

Operators decide to flare gas when doing so enables them to produce the more-valuable crude stream until equipment is installed to capture associated gas. They need to extract as much value from wells as possible by capturing and selling both oil and associated gas, but infrastructure constraints sometimes make that impossible. With crude oil prices now more than 30 times those of natural gas on an energy-equivalent basis, the incentive is very strong to produce oil and burn associated gas that has no route to market.

Flaring in North Dakota has grown rapidly because of the recent growth in production of oil and associated gas. Since January 2008, oil production in the state has risen by 500,000 b/d, and gas production (largely associated gas from Bakken shale wells) has risen by 500 MMcfd. Gas production has outpaced the installation of gas-gathering and treatment facilities.

Flaring and regulations

North Dakota was producing 660,000 b/d of oil and about 713 MMcfd of gas in June 2012. The vast majority of North Dakota's produced gas is associated with oil. About one third of the produced gas is being flared.

Millions of dollars have been deployed for natural gas infrastructure, and large outlays are expected over the next several years. Despite the large growth in gas capturing, gathering capacity has failed to prevent flaring.

Regulations in North Dakota allow companies to flare gas from an oil well for up to 1 year before being forced to shut in the well, pay royalties, or connect gas output to gathering lines and facilities so it can be used for on-site power or sold. Exemptions are permitted if a company can prove that it is not feasible to hook up the well to the necessary infrastructure.

If hookup is deemed infeasible, the North Dakota Industrial Commission (NDIC) grants the producer the right to continue flaring gas from the well for longer than 1 year. The NDIC says it periodically follows the activity of many of these wells to see if circumstances of the permit have changed. However, there are currently no regulations in place requiring follow-up.

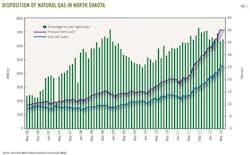

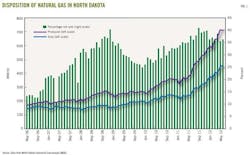

While new gathering lines and processing facilities are being put into place, a large gap remains between gas produced and gas sold. About 36% of produced natural gas is not being captured. However, not all of this is attributable to flaring. About 32% of the gas produced in North Dakota is being flared. Fireflooding for enhanced oil recovery in Bowman County accounts for 2-3% of the unsold gas (Fig. 1).

Because over 100 wells come on line each month (147 in June), the number of wells without gas sales remains above pre-Bakken boom levels; however, the growth in wells with gas sales (wells that are capturing gas) has far outpaced the growth of wells without sales (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2a indicates a steady increase in the number of new wells connected to a gathering system for the first time each month.

Infrastructure investment

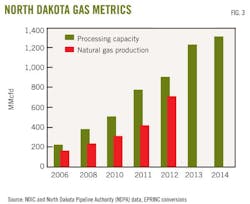

The oil and gas industry is investing $4 billion for gas gathering and processing in North Dakota from now until 2017. Currently, gas processing capacity in North Dakota is keeping up with production, but the continuation of flaring indicates delays in the building of infrastructure and connection of individual wells to gathering systems. The delays probably result from issues of rights of way and related effects on construction.

Fig. 3 shows how gas plant processing capacity has more than kept pace with gas production in North Dakota and is set to continue this pace. Table 1 shows planned investments for gas-gathering. Typically, the government of North Dakota approves permits within a few months; however, permitting alone does not secure the necessary rights of way needed by producers from landowners to build gathering pipelines from the wellhead.

Speed of development

Rapid oil development has occurred across a 15,000-sq-mile play since 2006 in North Dakota, and it is only now that companies are beginning to hold acreage by production. Many leases signed at the beginning of the boom in 2007-08 required companies to drill wells and begin production promptly, typically within 3-5 years. Flaring might have a chance to decline now that many companies are beginning infill drilling and holding their acreage by production. The NDIC estimates that in 2 years most acreage will be held by production in North Dakota with an average state rig count of 225 units.

The extent of development and speed at which wells come on line, over 100 wells/month, are important to understanding why every well is not immediately connected to a gathering line.

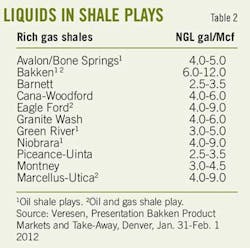

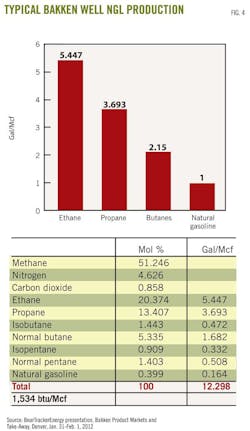

Many critics contend that companies are simply flaring associated gas from Bakken wells because, relative to oil, gas offers little value to the producer. Henry Hub gas prices are currently around $3/Mcf. In fact, Bakken gas is very rich in NGLs and offers considerable value to producers and midstream operators.

The Bakken is said to yield 6-12 gal of NGLs per thousand cubic feet of natural gas. This makes it one of the richer gas plays in the US. The cost of flaring thus is greater in North Dakota's Bakken than in other plays (Table 2).

The value of these NGLs varies according to the market but can easily add $6-12/bbl of oil if captured and processed. This is a strong incentive to the oil producer faced with transportation discounts that lower wellhead values of North Dakota crude oil because of distance to major refining centers.

While obtaining the necessary permits from the government of North Dakota has not been a large issue, obtaining rights of way from landowners is a rising obstacle. Due to the intense level of oil activity in the Bakken shale region, landowners are experiencing fatigue, and companies are experiencing increasing difficulty getting all the landowners along individual pipeline routes to agree to pipeline construction, whether for gathering gas or for moving crude.

The result is a lag between permit approval and construction completion. North Dakotans have expressed concerns about increased traffic from trucks moving equipment, supplies, and crude. New pipelines remove some of the trucks from the road, but resistance from landowners to pipeline construction delays the ability to remedy this problem.

State officials have been working with companies and landowners on these issues.

North Dakota in context

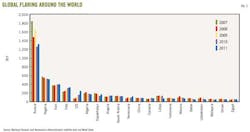

The World Bank recently published updated numbers on flaring across the globe showing the US had the highest increase in flaring in 2011. The bank pointed to North Dakota as the primary source for the increase. However, historical data correlated to increases in US production indicate that North Dakota may not be responsible for the majority of this increase.

Despite its world-leading increase last year, the US still flares a small fraction of the amount of the global leader, Russia. In 2011 Russia flared over five times as much gas as the US: 1.321 tcf vs. 251 bcf (Fig. 5).

The pace of oil development provides important context for flaring in the US. Since January 2008, production of crude oil has grown by over 1 million b/d and now is well over 6 million b/d. Many oil-producing regions, such as the Permian basin, have extensive legacy production. However, other plays, such as the Eagle Ford in southern Texas, have had little to no production and therefore have almost no infrastructure to manage the oncoming associated gas. Even the prolific Permian basin has infrastructure constraints as its older facilities are proving inadequate to handle vast new flows of oil and gas.

So much production growth in such a short period of time is historic, and the repeatability of high well performance is unprecedented. Wells in both the Eagle Ford in Texas and the Bakken in North Dakota often have initial production rates of 4,000 b/d of oil. They also produce associated gas at high rates. And while billions of dollars of investment are taking place across the US to build gathering and processing facilities to capture natural gas, flaring will not dwindle overnight. For example, when a new well comes on line at a high rate in North Dakota, previously connected wells sometimes must resume flaring so gathering pipelines can safely handle the new gas.

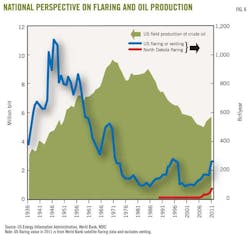

Fig. 6 shows that gas flaring and venting peaked in the 1940s, several decades before crude oil production peaked. Since then there have been several temporary increases in flaring and venting, notably in the 1960s as crude oil production was growing towards its peak. But flaring and venting have remained at 100-300 bcf/year since the late 1970s. Flaring and venting actually declined during 1976-85, when crude oil production grew by almost 1 million b/d. The spike in the mid-1990s corresponds to the same spike in Fig. 7, indicating that flaring and venting in Wyoming led to this increase.

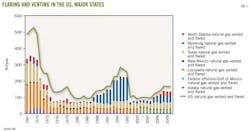

Fig. 7 indicates that while North Dakota flaring and venting (almost all flaring) have greatly increased, substantial amounts through 2010 are attributable to Texas and Wyoming.

Since 2009, Texas oil production has risen by nearly 800,000 b/d. This is due to booming oil and liquids-rich production in plays such as the Eagle Ford and Permian basin. Texas issued 306 flaring permits in 2010 and 651 permits in 2011.

Cost of prohibition

While flaring can be inefficient and harmful to the environment, prohibiting the production of crude oil has significant economic costs. A typical 2012 Bakken well has an expected production life of 45 years and will produce 615,000 bbl of oil. It creates $20 million in net profit, pays $4 million in taxes, $7 million in royalties, $2 million in wages, and $2 million in operating expenses, according to NDIC estimates.

The economic incentive for a producer is to connect a well to gas sales at the very beginning of the production cycle, when gas and oil flows are at their highest levels.

As Table 3 indicates, a well generates most of its lifelong value in first few years of production. And the value of oil far outweighs values of dry gas and NGLs with assumed prices of $3/Mcf for dry gas and $10/Mcf for NGLs.

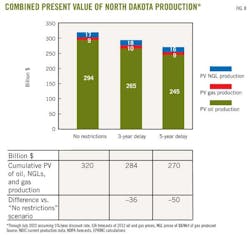

EPRINC constructed a present value (PV) model to analyze the financial incentives associated with natural gas flaring in North Dakota. These are financial calculations and do not take into account environmental gains or losses. The model examines the PV implications of banning any new flaring in order to construct sufficient infrastructure to capture all associated gas.

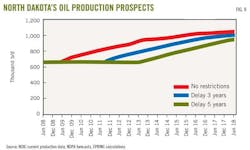

Scenarios were designed around hypothetical regulations prohibiting flaring gas and thereby foreclosing vast amounts of new oil production. The three scenarios include: no restrictions on new wells, continued gas flaring at a rate of 32% that declines by 2%/year during 2013-16 and 3%/year in 2017-22 as additional infrastructure is installed; a 3-year delay on new wells, subsequent 100% capture of natural gas, and 0% flaring; and 5-year delay on new wells, subsequent 100% capture of natural gas, and 0% flaring. These calculations assume a GOR of 1.079 Mcf/bbl of oil and reflect the North Dakota Pipeline Authority low-case oil forecast.

EPRINC's model holds oil production constant at the current level of 660,000 b/d in both the 3 and 5-year scenarios. This is based on an estimate that enough new oil production will come on line without creating additional flaring, offsetting production declines from existing wells. Continued drilling would be needed to maintain current production levels under the 3 and 5-year delay scenarios. This could take place without new flaring as new gathering infrastructure comes on line. Some new drilling will occur on developed acreage with existing gas gathering facilities.

Fig. 8 shows the combined PV of oil and gas production in North Dakota through July 2022 under the scenarios in EPRINC's analysis. PV variations against the "no-restrictions" scenario are essentially values lost due to flaring restrictions. With a 3-year delay in oil production due to regulations prohibiting flaring there is a PV loss of $36 billion. In the 5-year delay scenario, the PV loss is $50 billion.

Fig. 9 compares crude oil production in the three scenarios. Cumulative production for the scenario with no restrictions is 3.257 billion bbl; for the scenario with a 3-year delay it is 2.946 billion bbl; and for the scenario with a 5-year delay it is 2.714 billion bbl.

The authors

Trisha Curtis is a senior research analyst at Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc. She led EPRINC's assessment of the economic benefits of the Keystone XL Pipeline project and the report on North Dakota's Bakken boom. She is leading research efforts on the potential of the Bakken and other shale oil plays to expand US field production. She holds a master's degree in international political economy from the London School of Economics and holds undergraduate degrees in economics and politics from Regis University, Denver.

Tyler Ware is a research analyst at EPRINC. He is a 2010 graduate of Williams College, where he studied political economy. He worked with EPRINC as an intern during his college years and recently returned as an independent consultant providing research assistance and business support.