The Natural Gas Council, an organization of groups from all phases of the US gas industry, released an independent guide to 75 different studies of methane emissions from gas systems. The ICF International report, “Finding the Facts on Methane Emissions: A Guide to the Literature,” found several recurring findings.

“The report identified some commonalities and overarching themes that the council hopes policymakers will use to inform their decisions on methane released from natural gas systems,” said Dena Wiggins, president of the Natural Gas Supply Association, where the guide was released on Apr. 26. “It specifically warns against basing policies on a single study’s conclusions.”

Methodology used in each of the 75 studies had a large effect on the conclusion, the report found. It said that direct measurement, or “ground up,” studies found that a few super-emitter sites represented a disproportionate share of industry emissions. Ambient measurement, or “flyover,” studies showed a wide range of results affected by weather and other potential methane sources, while life-cycle analyses showed life-cycle gas emissions that were 40-50% lower than other fossil fuels, it indicated.

“The study helps place the methane emission issue in perspective, since many other studies have been made already. It’s important that we all speak the same language,” said Interstate Natural Gas Association of America Pres. Donald F. Santa, who briefed reporters with other council members’ representatives at NGSA’s headquarters.

“This is a high priority for this administration and [the US Environmental Protection Agency,]” he said. “No matter which study you look at, there are some sources that are the biggest emitters. That’s where we should focus for the most bang for the buck. Possible service disruptions also should be considered.”

Direct measurement studies found that most sources emitted less than estimated as well as a few super-emitters, according to Joel Bluestein, the ICF senior vice-president who oversaw the new guide’s preparation. A problem with ambient studies is that they don’t always show emissions’ origins, he said. “You really need to know where they’re coming from—not only oil and gas operations, but landfills, feedlots and other sources,” he said. “Once these are identified, it’s easier to calculate actual emissions by source.”

Why wellhead estimates grew

EPA revised its annual greenhouse gas inventory methodology earlier this year and made news when it announced that releases at the wellhead were 12-13% higher, Bluestein said. Part of this may have been due to higher production, but EPA also included data from gathering systems for the first time, he said.

“Emissions have been going down since 1990 in absolute terms, particularly per unit of gas,” Bluestein said. “Almost half of this reduction is due to three causes: equipment replacement, voluntary actions, and new regulations in the last year. Methane’s share of total GHG emissions has not changed much—it’s in the 2.4-2.6% range. We’re getting better information. You can measure hundreds of facilities, but there are thousands out there. We could be doing better.”

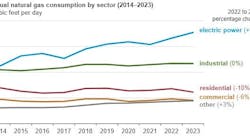

Not all the association representatives felt that EPA needs to impose more GHG regulations to curb emissions. “We think it’s heading down the wrong track, since emissions have been going down with more requirements,” said Kyle Isakower, the American Petroleum Institute’s vice-president of regulatory and economic policy. “Emissions have been going down without them. Natural gas is the single reason why our GHG emissions are at their lowest levels in 20 years.”

“Emissions can be reduced more, but you also need to find more of the leaks,” said Pam Lacey, chief regulatory council at the American Gas Association. “That requires new technology, which [the US Department of Energy] is trying to develop at its ARPA-E program. Better data will show where controls would be most effective.”

Matthew Hite, vice-president of government affairs at the GPA Midstream Association, the former Gas Processors Association. “Gathering lines are an infrastructure issue. Getting them permitted can take years,” Hite observed.

“We also need to address training employees and third-party contractors,” Santa noted. “That would be hard if EPA requires compliance within 90 days. There are a lot of overlaps if you look at what the various agencies are doing. [The US Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration] is proposing periodic tests of pipeline segments. That can require blowdowns, which raise new methane emissions questions.”

Contact Nick Snow at [email protected].