PIRINC: Refiner consolidation not a cause of gasoline price spikes

Sam Fletcher

OGJ Senior Writer

HOUSTON, May 6 -- Competition among US refiners is still strong, said the Petroleum Industry Research Foundation Inc. (PIRINC), prior to hearings Tuesday by a Senate subcommittee investigating whether industry mergers have pushed up US gasoline prices at the pump.

"It would be wrong to conclude that the US refining industry has become less competitive since 1996. National concentration levels in refining remain relatively low in comparison with other US industries, and in any event, most economistsand antitrust regulators and the courtslong ago abandoned the dogma that increased concentration in itself is anticompetitive," said the PIRINC report authors Larry Goldstein, Ron Gold, John Lichtblau, and Jim Arrowsmith.

During the last few years, PIRINC acknowledged, "there has been significant turnover among the largest refiners, encouraged by Federal Trade Commission actions." But at the same time, it noted, "The FTC has acted to curb what was believed were potential threats to competition, requiring divestitures in certain cases where it believed necessary while not objecting to consolidations where it saw no potential anticompetitive effects."

Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich), chairman of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, released his own report Monday alleging that consolidation of the refining industry forced gasoline prices up by reducing supply. Subcommittee staff members criticized the legal practice of "zone pricing" to charge different prices for gasoline to different station operators, some of which are in nearby geographic areas, in order to "confine price competition to the smallest area possible and to maximize their prices and revenues at each retail outlet."

The report said oil companies sought to circumvent antitrust laws by shrinking the size of the zone in some cases to just one retail outlet.

Levin began hearings Tuesday on his subcommittee's 10-month investigation of gasoline prices. Officials from industry, academia and state government were scheduled to testify Tuesday and Thursday (OGJ Online, Apr. 30, 2002). Industry witnesses expected to testify include executives from BP America Inc., ExxonMobil Corp., Marathon Ashland Petroleum LLC, ChevronTexaco Corp., and Shell Oil Co.

Refiner mix changed

A series of major mergers in the past 6 years created some "supermajors," such as ExxonMobil and ChevronTexaco but also transformed some smaller companies, including some independents, into major players among refiners. "This process has boosted concentration levels in the US refining sector and at the same time changed the mix of players," said PIRINC researchers.

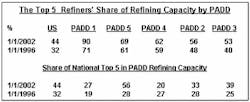

As a result, the five largest US refiners accounted for 44% of total US crude refining capacity (crude distillation) at the start of this year, up significantly from 32% at the beginning of 1996. But there also was "a noticeable turnover" among the leading refiners "with Phillips (Petroleum Co., Bartlesville, Okla.,) and Valero (Energy Corp., San Antonio) climbing up into the national top five and Shell dropping out," said PIRINC.

The five largest US refiners are ExxonMobil, with 12% of all US refining capacity; Phillips, 10%; BP, 9%; Valero, 7%; and ChevronTexaco, 6%.

Moreover, PIRINC said, "The FTC focuses on conditions in specific geographic markets, not national concentration statistics. Any assessment of the impact of recent mergers on competition must also consider regional impacts rather than simply changes in the national aggregates."

Looking at which refiners control what capacity in the five US Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts (PADD), PIRINC concluded, "There is an important distinction between the largest refiners on a regional basis and the largest refiners nationally." The biggest refiners nationally are not always the biggest players, or even present, in each PADD.

Due to staff and time constraints, the investigation launched by Levin's staff in June 2001, following dramatic gasoline price spikes in the Midwest, focused on three regions: the West Coast, California in particular; the Midwest, primarily Michigan, Ohio, and Illinois; and the East Coast, with a special emphasis on Maine and the Washington, DC, area.

However, PIRINC analysts said a close look at the refining capacity in those areas doesn't support the subcommittee staff's allegations.

In PADD 1, which extends the length of the US East Coast, they said, "The national top five currently have only a 27% share of refining capacity within the region, up somewhat from 19% in 1996 and well below the current 90% share of the top five refiners operating within the region.

"Of the national top five, only Phillips and Valero have any refining capacity within the region. The largest refiner within PADD 1 is Sunoco (Inc., Philadelphia,) with a 32% share of local capacity as opposed to a 4% share of national capacity in 2002."

What's more, they said, "None of the mergers of recent years has involved an FTC-required divesture of PADD 1 refining assets, in part reflecting the relatively modest presence of the largest national refiners."

In PADD 2, which encompasses the upper Midwest US, the top five local refiners made "only a modest increase" to a 56% share from 48% in 1966. The share commanded by the five largest national refiners "is much lower, 33% in 2002, and only marginally higher than in 1996," said PIRINC. The largest refiner in that region is Marathon Ashland, with some 18% of PADD 2 refining capacity and a 5.5% share nationwide.

The region also is open to competition from outside sources. Refiners in PADD 3, which includes Gulf Coast states from Texas to Alabama, along with New Mexico and Arkansas, supply almost 20% of PADD 2's gasoline demand. "External supply potential is growing with the introduction of the Centennial Pipeline running from Beaumont, Tex., to Bourbon, Ill.," PIRINC reported.

PADD 5, which includes the US West Coast, Alaska, and Hawaii, "is different," said PIRINC.

"Here, not only is the share of the largest regional refiners high at nearly 70%, but the presence of the largest national refiners is high as well. Moreover, the particular CARB reformulated gasoline specifications have left this market less accessible to suppliers from outside the region," PIRINC reported. "This is the region where the FTC has been most active in requiring divestitures of refining assets."

Price Spikes

Gasoline price spikes experienced by US motorists in 2000 and again in the first half of 2001 were especially acute in California and the Chicago-Milwaukee area.

However, PIRINC analysts reported, "The spikes did not reflect any lack of competition among refiners. They have resulted from infrastructure bottlenecks, including tight refining capacity, as well as stringent, location-specific polices regulating product quality."

Those price run-ups eventually were eased "first by exceptionally high refinery runs and then by a weakening economy and seasonal demand declines."

PIRINC said, "At the beginning of this year, retail prices were down about 60¢/gal from their spring peak, far more than then 21¢/gal decline in crude prices for the same period. But structural problems remain and show signs of reemergence as strong economic recovery and rising demand, as well as rising crude prices, fuel upward movements in gasoline prices."

It concluded, "Some steps have been taken to ease local problemsor at least to avoid further aggravating them. But more is needed. Misplaced concerns over industry concentration must not divert policy-makers from a serious discussion of this issue."

Contact Sam Fletcher at [email protected]