Preliminary assessment of Arab Spring's impact on oil and gas in Egypt, Libya

Gawdat Bahgat

National Defense University

Washington, DC

Popular movements toppled the leaders of Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya in 2011, and these uprisings are likely to have short and long-term impact on these societies with global ramifications.

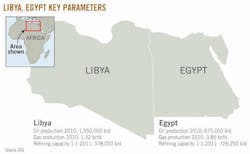

This study focuses on Egypt and Libya and highlights how the oil and gas industry in these two North African countries has been impacted by political upheavals. Specifically, I examine the impact on production, consumption, shipping, and investment.

Objects of the tumult

The year 2011 was, by all accounts, a turning point in North Africa and the broader Arab world.

Popular movements toppled three dictators—Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia, Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, and Moammar Gaddafi in Libya. The echoes of these uprisings can be seen and heard in other Arab countries, particularly Yemen, Syria, and Bahrain, among others.

The new leaders are trying to establish new institutions and articulate new strategies. It is uncertain whether they will succeed. What is certain, however, is that these uprisings have fundamentally impacted the socioeconomic and political structures.

The oil and gas industry is the dominant sector in several Arab countries.

Revenues from oil and gas exports provide the largest share of national income in producing countries. Less-fortunate countries depend heavily on remittances sent by their labors. Indeed, it can be argued that the economies in the entire region are driven by oil, though in different forms and at different degrees.

Equally important, the global economy depends heavily on oil and gas supplies from the Middle East. This means that stability in the region is crucial to the global economic prosperity. In short, the upheavals that have strongly shaken Arab regimes are likely to have great impact on the management of the most important industry—oil and gas—with strong regional and international implications.

Two areas are likely to be negatively affected by the Arab Spring: domestic consumption and foreign investment.

Domestic consumption

The Arab world holds 49.6% of the world's proved oil reserves and 29.1% of natural gas.1 These massive reserves have shaped public perception.

In the land of oil and gas many people believe it is their birthright to consume as much of their hydrocarbon wealth at low price. No wonder fossil fuel consumption per capita in the Arab world is among the highest in the world.

This high level of consumption is fueled by generous state subsidies. All over the Middle East, prices of petroleum and petroleum products are very low and do not reflect the market value. This uncontrolled high and growing consumption also means that these major oil exporters will have less oil available for export in the near future.

Many Arab governments have recently thought to reduce consumption by cutting off subsidies. The challenge was (and still is) how to deal with the certain resistance by the majority of their populations.

In order to restrain public rage and diffuse tension, Arab countries in the Gulf have substantially increased public spending.

Popular protests did erupt in Algeria at precisely the same time as they were enveloping neighboring Tunisia and Egypt, but the demands of the protesters never formed a unified movement calling for the toppling of Pres. Abdelaziz Bouteflika (in power since 1999).

The Algerian authority took these demonstrations seriously and responded by repealing the emergency laws that had been in place for 19 years2 and by increasing public spending and promising more social housing, higher public-sector salaries, increased subsidies for basic food products, and easier access to credit for young people.3

The less affluent countries in North Africa cannot match the packages offered by the Gulf States and Algeria but are not likely to reduce subsidies. In short, the hesitant attempts to reform energy prices and bring them closer to market values have been put on the back burners in most Arab countries.

Foreign investment

The International Energy Agency estimates that the world will need $10 trillion of investment in the oil sector and $9.5 trillion in the natural gas sector in 2011-35.4 It also projects that most oil and gas supplies will come from the Middle East. In other words, to meet the growing global demand, substantial investments have to be made to develop oil and gas deposits in the Middle East.

Most of these investments are likely to come from international oil companies (IOCs). These IOCs generally prefer to invest in stable regions. True, there are attractive opportunities in Libya, Egypt, and others, but security and stability have to be restored first to attract foreign investments. Furthermore, new deals are likely to be closely scrutinized due to the growing public demand for transparency and accountability.

In addition to these general implications, each Arab country has responded to the Arab Spring in a unique way, based on its history, culture, and the overall socioeconomic and political structure. In the following two sections I closely examine the impact of Arab Spring on oil and gas industry in Egypt and Libya.5 The analysis highlights the similarities and differences between the two North African states.

Egypt

Domestically and internationally three sections in Egypt's energy sector are particularly important: oil and natural gas production, refining, and shipping (Suez Canal, SUMED, Arab Peace Pipeline).

The toppling of the Mubarak regime had little if any impact on production and refining. Similarly the transportation of oil and gas through the Suez Canal and SUMED was not interrupted. The biggest impact was the repeated attacks on and sabotage of the pipeline that carries natural gas to Israel (and Jordan).

Egypt is not a major oil producing country. The nation's oil production peaked in 1996 at 935,000 b/d and has since declined (736,000 b/d or 0.9% of world's total in 2010). Despite new discoveries and enhanced oil recovery techniques at mature fields, crude oil production continues its decline.6 In 2010 consumption reached 757,000 b/d, which means that Egypt has to rely on foreign imported supplies to meet its growing needs.

The decline in oil production has been offset by the rapid development of the natural gas sector for both domestic consumption and export. Over the past decade, Egypt has emerged as a key gas producer and exporter.

Egypt holds the third largest proved gas reserves in Africa after Nigeria and Algeria. From 2000 to 2010 the country's production grew threefold to 62.7 bcm from 21 bcm. This impressive surge in production, however, was restrained by a rapid rise in consumption. During the same decade consumption more than doubled to 45.1 bcm in 2010 from 20.0 bcm in 2000.

The impact on production and consumption is mixed. Oil and gas fields were not attacked during the uprising that toppled Pres. Mubarak. Still, the government has been actively trying to attract foreign investments to increase exploration and production. The volume of foreign investment is likely to reflect and to be driven by the level of political and economic stability in post-Mubarak Egypt.

Furthermore, prior to the uprising, the government planned to reduce and slow the rapid rise in energy consumption by gradually targeting subsidies. Given the public anger over high prices, it is highly unlikely that reforming energy prices will be a major priority to the new leaders in Cairo. Instead, increasing public spending and maintaining public subsidies are likely to prevail.

With 10 refineries, Egypt has the largest refining sector in Africa. Indeed, refining capacity exceeds domestic demand, which prompts Cairo to import crude oil, process it, and export it.

In recent years plans were made to further expand the country's refining capacity. Such plans require substantial foreign investments. Again, securing these investments requires stable economic and political environment and improved internal security.

Suez Canal and SUMED pipeline

Egypt plays an important role in international energy markets through the operation of the Suez Canal and SUMED pipeline, two routes for the export of Persian Gulf oil and LNG. Fees collected from operation of these two transit points provide a large source of revenue for the Egyptian government. Meanwhile, disruptions of shipments, as will be discussed below, would have negative implications on consuming markets particularly in Europe.

The Suez Canal connects the Red Sea and Gulf of Suez with the Mediterranean Sea, spanning 120 miles. The canal is a two-way street: crude oil and oil products are shipped in both directions, north to the Mediterranean and south to the Red Sea. Traffic of LNG through the canal is dominantly northbound, mostly from Qatar to Europe and the US.

In late 2000s about 1% of global crude oil supply, or 5% of seaborne oil trade, was shipped through the canal.7 This volume is substantially smaller than a few decades ago. Shipment through the canal was completely blocked in 1956 and 1967-75 due to wars with Israel. This disruption of shipments, among other developments, was a major reason for finding alternative shipping lanes.

The 200-mile long SUMED pipeline provides an alternative to the Suez Canal for those cargoes too large to transit the canal. It was built largely in response to the extended closure of the Suez Canal following the 1967 war with Israel.

SUMED connects the Red Sea with the Mediterranean with an estimated capacity of 2.4 million b/d (not all this capacity is utilized). It runs from south to north, supplying the Mediterranean with oil from the Persian Gulf. It is owned by the Arab Petroleum Pipeline Co., a joint venture between the Egyptian General Petroleum Corp., Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi's national oil company, Kuwaiti companies, and Qatar Petroleum Corp.

Total oil flows through the Suez Canal and SUMED have declined since 2008 due to three developments.

1. The global economic slowdown has led to large reduction in oil demand and consumption. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, mostly Persian Gulf producers, responded by cutting production and-or suspended adding new volumes. This caused a sharp fall in regional oil trade.

2. Since the mid-2000s there has been a fundamental change in the dynamics of global oil markets. Asian countries (particularly China and India) are consuming and importing more oil than Europe and the US. In other words, more oil has been shipped east instead of west.

3. Piracy and security concerns around the Horn of Africa have led some exporters to travel the extra distance around South Africa to reach western markets.

Unlike oil, LNG transit through the Suez Canal has been on the rise. Northbound transit is mostly from Qatar (and to a much lesser extent Oman) destined for European and North American markets. Southbound transit is mostly from Algeria and Egypt and destined for Asian markets.

Closure of the Suez Canal and the SUMED pipeline would divert oil and LNG tankers around the southern tip of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope, adding distance, transportation time, and shipping costs. During the 2011 uprising that toppled Pres. Mubarak there was no interruption in shipping via the canal or SUMED. Still, it is not clear if the Suez Canal authority will have the necessary funding to carry on the ambitious plans to enhance and enlarge the canal.

Egypt gas exports to Israel

The biggest impact of the 2011 uprising is on Egypt's natural gas export to Israel. In 1979, Egypt became the first Arab country to sign a peace treaty with Israel. Since then, the Egyptian-Israeli relationship has been through several ups and downs, but the two sides have managed to maintain peace. This peace, however, is often described as "cold." Generally, Egyptians are not enthusiastic about having close cultural and economic ties with the Israelis.

Despite this lack of enthusiasm, the Egyptian government signed a 15-year agreement with Israel in 2005. According to this pact, Egypt agreed to supply 60 bcf/year of gas to Israel via an undersea pipeline from the north Egyptian town of El-Arish to the southern Israeli coastal city of Ashkelon beginning in 2008. The agreement was executed by the East Mediterranean Gas Co., a consortium of the Egyptian General Petroleum Corp., Merhav of Israel, and Egyptian businessman Hussein Salem.

With the toppling of the Mubarak regime, the pipeline has been attacked several times and supplies were interrupted.

Former energy officials, including Minister Sameh Fahmy, are under investigation on charges related to the gas deal with Israel. The public prosecutor accuses these former officials of "squandering public funds" by permitting East Mediterranean Gas to trade with Israel at prices below global market rates. At least four factors contributed to this public backlash against supplying gas to Israel.

First, despite the peace treaty and close relations between the Mubarak regime and Israel, many Egyptians still see Israel as an enemy that occupies Arab and Muslim land. Exporting gas to Israel has always been unpopular, and activists tried to stop these shipments through the courts even before the fall of President Mubarak.

Second, domestic consumption of gas is very high in Egypt due to heavy government subsidies. The combination of a large population and generous subsidies means that a small and shrinking volume of gas is available for export.

Third, though there is no global benchmark price for natural gas, comparable deals in the region show that Turkey, Greece, and Italy were paying double the price Israel was paying for imported gas.8 Finally, the Egyptian government's control over Sinai has never been strong, and the bedouins and other groups who resent or oppose the government in Cairo see the pipeline as an easy target.

Libya

The impact of the Arab Spring on energy sector in Libya was much bigger and multidimensional than in neighboring Egypt. The process of toppling President Mubarak was less violent and lasted only for a few weeks.

On the other hand, Libya witnessed intense fighting between pro and anti Gaddafi forces that lasted for several months. Foreign military assistance and the NATO aerial campaign played a large role in defeating Gaddafi's loyalists.

Not surprisingly, given the intensity and speed of the process that led to regime change, the toppling of Mubarak was done without losing a single barrel of oil. Indeed, as discussed above, the major impact is on natural gas supplies to Israel.

In Libya, on the other hand, the oil industry was virtually paralyzed and some oil fields, refineries, and terminals were attacked.

Large reserves, underexplored resources

Libya holds 3.4% of the world's proved oil reserves—the largest in Africa.

In addition, Libya's oil sector enjoys two important advantages. First, the country is located on the opposite side of the European market. Despite genuine efforts to diversify Europe's energy mix, most European countries remain heavily dependent on imported oil. Geographical proximity means that Libyan oil is easy and cheap to import.

Second, unlike a large proportion of oil from the Persian Gulf region and elsewhere, Libya produces one of the highest-quality and low-sulfur oil—light and sweet crude. Generally, this crude is the easiest to process and can be run by relatively "simple" refineries that may not be able to handle heavier or sourer substitutes.

A loss of light, sweet crude volumes is more difficult to deal with than a loss of heavier and sourer ones. This is not only because the refineries that run light, sweet grades have limited feedstock flexibility but also because most of the spare crude production capacity tends to be at the heavy, sour end of the barrel.

In short, Libya's importance to the oil market stems not only from its substantial production, but also from the light sweet quality of its crude grades.9

Unlike gulf producers such as Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia where oil was discovered early in the 20th century, oil in Libya was discovered late in the 1950s. In a short period of time oil production was brought on stream, particularly from the Sirte basin, and by the late 1960s Libya had become the world's fourth largest exporter of crude oil.10

This large volume of production and export, however, drastically declined during most of the following four decades. This decline was the outcome of misguided policy pursued by the Gaddafi regime. Compared with other oil producers, Libya offered few incentives to attract international oil companies (IOCs). Furthermore, comprehensive international sanctions were imposed on Libya in response to sponsoring terrorist attacks and seeking to develop weapons of mass destruction.

After these sanctions were finally lifted in the early 2000s, the prospects of Libya resuming its leading role as a major oil producer and consumer seemed promising. Historical deals were signed with IOCs such as BP of Britain and Eni of Italy, among others. These promising prospects, however, did not last long.

The Libyan authorities were not enthusiastic about encouraging foreign investment. Oil companies labored under a crushing bureaucracy including the stipulation that they had to hire Libyans for top jobs despite the small pool of nationals with the appropriate technical and managerial skills.11 Thus harsh fiscal terms combined with institutional and administrative deficiencies have led to a gradual fading of foreign oil companies' interest in Libya.

This brief review of Libya's oil industry suggests that the country's massive oil resources remain largely unexplored. The absence of international oil companies means that the most updated technology in exploration has yet to be used. There are outstanding prospects for large discoveries.

The full utilization of the country's hydrocarbon resources is particularly important given that oil export revenues account for about 95% of the country's hard currency earnings and more than 70% of gross domestic product.12

Restoring infrastructure, production

This urgent need to resume production has to overcome the unspecified destruction of the country's oil infrastructure. Oil wells need constant maintenance, and after 6 months of stoppage facilities could have suffered considerable damage.

Libya has six main terminals, and at least two of them, Es Sider and Marsa el Brega, were heavily damaged.13

Despite the focus on oil exploration and development, Libya has massive untapped natural gas resources. The country became a gas exporter in 1971, when a liquefaction plant at Marsa el Brega became operational.

After early pricing disputes, exports built up to a peak of 3.6 bcm in 1977, but in 1980 the government nationalized the facilities from Esso (now ExxonMobil) and imposed higher prices.14 The main buyers of the facility's LNG either cancelled their contracts or scaled down their purchases.

For the next 2 decades the development of the industry had been slow partly because of economic sanctions and partly because of official lack of interest.

In the early 2000s, however, the gas industry experienced a revival. The subsea Green Stream Pipeline connecting Libya and Italy was inaugurated in October 2004. This 340-mile pipeline is a joint venture of Eni and the National Oil Corp. of Libya.15

Eni closed the pipeline in February 2011 when the violence erupted but reopened it late in the year. The resumption of gas exports is a major step.

More important is the return of Libya's full oil production and export. Several major international companies such as Eni, Repsol of Spain, Total of France, Wintershall of Germany, and US-based Occidental Petroleum, ConocoPhillips, Hess, and Marathon have already expressed interest in resuming operations in Libya, and some have sent representatives to negotiate their return. It is unclear when Libya's production will reach the precrisis level.

Analysts have speculated on how long it will take the new Libyan authority to repair the damage in the oil infrastructure. The experience in other major producers who went through political upheavals underscores that political stability, improved security, along with stable legal and institutional framework are prerequisites.

The examples of Iran, Kuwait, Russia, Nigeria, and Iraq suggest that Libya might need 3-4 years to restore production to the precrisis level.16 The interim government decided not to award new oil concessions or make major economic decisions, saving those for a future elected leadership.17

The technical and political challenges facing the Libyan authorities are immense. They have to repair the damaged oil fields, terminals, and other installations. Equally important, they have to create new political institutions, security forces, viable bureaucracy, and agree on constitution.

Unlike Egypt and Tunisia, who inherited these institutions, the new Libyan authority has to start from scratch.18 On the positive side even after a long and costly civil war, the Libyan authority has inherited substantial financial assets. In addition, IOCs are eager to invest in Libya's oil and gas sectors.

References

1. British Petroleum, BP Statistical Review of World Energy, London, 2011, pp. 6 & 20.

2. Darbouche, Hakim, "Algeria's Failed Transitions to a Sustainable Polity Coming to Yet Another Crossroads," accessed Nov. 3, 2011 (http://www.medpro-foresight.eu).

3. Dessi, Andrea, "Algeria at the Crossroads, between Continuity and Change," accessed Nov. 3, 2011 (http://www.iai.it).

4. International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook, Paris, 2011, p. 8.

5. Tunisia itself is a relatively marginal player. However, it is an important transit country because Algerian gas flows across it to Italy through the Trans-Med pipeline.

6. Energy Information Administration, "Country Analysis Briefs—Egypt," accessed Feb. 20, 2011 (http://www.eia.doe.gov).

7. Energy Information Administration, "Facts on Egypt: Oil and Gas," accessed Feb. 14, 2011 (http://www.eia.doe.gov).

8. MacFarquhar, Neil, "Mubarak Faces More Questioning on Gas Deal with Israel," New York Times, Apr. 22, 2011.

9. Energy Information Administration, "Libyan Supply Disruption May Have Both Direct and Indirect Effects," accessed Apr. 6, 2011 (http://www.eia.doe.gov).

10. Gurney, Judith, "Opportunities and Risk in Libya," Energy Economist Briefings, No. 221, March 2000, pp. 1-8.

11. Chazan, Guy, "For West's Oil Firms, No Love Lost in Libya," Wall Street Journal, Apr. 15, 2011.

12. International Monetary Fund, "Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East and Central Asia," Washington, DC, 2011, p. 14.

13. Javier Blas, "Lost in the Sands—Libya's Oil Industry; the Uprising Has Taken a Heavy Toll on an Industry Crucial to a Post-Gaddafi Revival," Financial Times, Sept. 20, 2011.

14. Martin Quinlan, "Gas Exports Set to Escalate," Petroleum Economist, Vol. 71, No. 3, March 2004, pp. 6-9.

15. Watkins, Eric, "Eni Aims to Re-launch Libya's Green Stream Pipeline by Mid-October," Oil & Gas Journal Online, accessed Sept. 6, 2011 (http://www.ogj.com).

16. Alhajji, Anas F., "Oil Production Capacity-Building Experience Has Implications for Libya," OGJ, accessed Oct. 3, 2011 (http://www.ogj.com).

17. Associated Press, "Major Economic Steps by New Libya Leaders Unlikely," accessed Nov. 10, 2011 (http://www.nytimes.com).

18. Darbouche, Hakim, and Fattough, Bassam, "The Implications of the Arab Uprisings for Oil and Gas Markets," Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, London, 2011, p. 14.

The author

Manuscripts welcomeOil & Gas Journal welcomes for publication consideration manuscripts about exploration and development, drilling, production, pipelines, LNG, and processing (refining, petrochemicals, and gas processing). These may be highly technical in nature and appeal or they may be more analytical by way of examining oil and natural gas supply, demand, and markets. OGJ accepts exclusive articles as well as manuscripts adapted from oral and poster presentations. An Author Guide is available at www.ogj.com, click "Home" then "Submit an Article." Or, contact the Chief Technology Editor ([email protected]; 713/963-6230; or, fax 713/963-6282), Oil & Gas Journal, 1455 West Loop South, Suite 400, Houston TX 77027 USA. |

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com