Trends emerge on hydraulic fracturing litigation

Barclay Nicholson, Kadian Blanson

Fulbright & Jaworski LLP

Houston

A review of lawsuits involving fracturing and general themes and theories of current cases can reveal trends that are emerging from this body of litigation, and one can make some predictions about what is on the horizon.

These are important times for anyone in the natural gas industry because hydraulic fracturing will be required to access most of the sizable US recoverable gas reserves, estimated at about 1,176 tcf.1

Fracturing

Despite its history and effectiveness, fracturing has recently come under increasing scrutiny. Specifically, while the fluids used in fracturing consist predominantly of water, many allege that they also contain small amounts of toxic chemicals. Because fracturing uses large volumes of water, it also results in large volumes of flowback or produced water, which allegedly still contains trace amounts of chemicals.

Critics allege that flowback water can seep into nearby groundwater, polluting drinking water sources and affect long-term health.

The response to these alleged risks is still being calibrated, with courts, state and federal regulatory agencies, and energy companies. All are beginning to grapple with potential consequences on the environment.

Fracturing discharge already has been blamed for contaminating water in Arkansas, Colorado, Louisiana, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, and West Virginia, resulting in several suits seeking damages for harm to physical property, as well as health.

In addition, many states either through their legislatures or their regulatory agencies have begun supervising the fracturing process more closely, and in some instances, curtailing it substantially.

Even more telling, Congress recently issued a directive to the US Environmental Protection Agency to assess whether fracturing poses a risk to drinking water.

In response, EPA prepared a draft study, which currently is undergoing review by EPA's science advisory board. The initial results of the study will be available in 2012.

Perhaps more important than looking at any issue separately is to glean what are the emerging general trends of this litigation and to make predictions about what is on the horizon.

Fig. 1 shows the hydraulic fracturing lawsuits and complaints by state.

Looking to the future

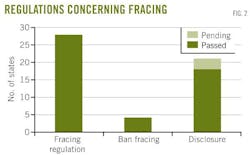

As it stands now, it seems unlikely that most states, especially those that are traditionally energy-resource friendly such as Texas or Oklahoma, will ban hydraulic fracturing outright or even regulate it to an extent that would discourage development.

That being said, the growing trend makes it likely that most areas with fracturing activity will adopt regulations requiring disclosure of chemicals used (as Texas recently did and as the governor of Colorado recently announced his state was considering) as a prerequisite for granting a permit.

In addition, states may adopt additional regulations for well operations that are more onerous than those placed on traditional oil and gas wells, as West Virginia has. These regulations require operators of wells that will be frac stimulated to submit a plan for how they intend to impound waste water to prevent contaminating nearby drinking water sources.

The results of the EPA study could have two prominent results. First, litigants likely will use the results as evidence of either the danger or lack thereof of the activity.

Second, the study may encourage or discourage lawmakers from bringing hydraulic fracturing within the scope of the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act.

Finally, much of the threat of water contamination predominantly arises when the energy company allegedly is deficient in casing the well. As the draft study itself mentions, proper well design and construction can play a major role in preventing contamination. As such, it is quite possible that EPA will conclude that mandates and design regulations are needed to ensure well integrity. Further, the industry has recognized the importance of educating the public about the effect of well design and geology in preventing potential consequences on aquifers, as is evident from television commercials on the subject.

While the imposition of these regulations would come with additional regulatory costs of compliance, at this point, there does not appear to be anything on the horizon that could fundamentally jeopardize the continued expansion of shale gas development.

Perhaps the most likely scenario is that the EPA study will affirm the conclusions of other recent studies, which conclude that hydraulic fracturing does not pollute groundwater, nor does it pose a disproportionate threat to public health and safety when compared to other resource extracting operations.

For instance, a study commissioned by the British Parliament recently determined, in authorizing the use of hydraulic fracturing in the UK, that there was no evidence that fracturing posed a direct risk to underground water aquifers provided that the drilling well was constructed properly.2

A recently released Duke University analysis of 68 private groundwater wells across Pennsylvania found that, while those wells near fracturing sites did have increased concentrations of methane, they were not contaminated with drilling toxins. Though based on a limited sample size, the study found no evidence of contamination from the chemicals used in the fracturing, which are often the focus of litigation and public health fears.3

On May 2, 2011, the University of Texas announced a $300,000, 9-month study to explore further the validity of continuing allegations that fracturing can contaminate or pollute groundwater. Based on what has gone before, including years of experience with well-fracturing technology designed to stimulate production of hydrocarbons, a report different from previous findings would appear unlikely.4

The most significant threat then, from a regulatory perspective, is not disclosure or well-design mandates or the conclusions of the EPA study, but rather the potential for delays in granting permits by state agencies paralyzed by political pressure. Furthermore, with the exception of an outlier Arkansas case that alleges that hydraulic fracturing causes earthquakes, development of tort law associated with fracturing operations also does not at the moment appear to present a substantial threat to the industry.

While it is true that a couple of cases have settled for reasonable sums, so far it would appear that the majority of pending cases does not contend that fracturing itself invariably pollutes the local air and water, but rather alleges that the particular practices of the operations in question were poorly managed. Therefore, case law developed from such operations may come to resemble case law applicable to other oil and gas exploration and production operations, as well as general tort law associated with operations of many other industries, where companies are sued for negligent operations, but the majority of the industry is able to continue on, largely unhindered.

Fig. 2 shows the number of pending and passed regulations concerning hydraulic fracturing.

Pending legal disputes

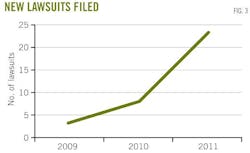

Since 2009, when the first lawsuits alleging contamination as a result of hydraulic fracturing were filed, there has been a small wave of litigation by landowners seeking damages from energy companies who engaged in fracturing on or near their properties. These suits share a number of common elements, including similar types of plaintiffs, similar causes of actions, and similar damages claims. In addition, the lawsuits typically name the same defendants, usually joining the owner (lessee) and or operator of the well along with the drilling company.

Notably, the focus of the bulk of these lawsuits, while they may allege property damage or the like, is that the fracturing process allegedly polluted the plaintiffs' groundwater or drinking water, purportedly leading to serious health problems.

Some of the earliest cases, which give a flavor to this type of litigation, were filed in Pennsylvania in fall 2009. As is common to this sort of litigation, these cases typically were brought by landowners who alleged that the defendant's hydraulic fracturing operations leaked chemicals into their water supplies, either aquifers or wells.

The plaintiffs based their claims in each of these suits on several common legal theories, including negligence, because the leaks allegedly resulted from improper protective casing of the well, negligence per se, invoking supposed violations of the Pennsylvania Oil & Gas Act or the Pennsylvania Hazardous Sites Cleanup Act, as well as fraudulent misrepresentation and breach of a contract.

These latter two claims are based on the plaintiff's allegations that the energy companies made promises regarding either safety procedures or the potential risk of toxic leaking and subsequently violated those agreements.

In the bulk of these cases, the plaintiffs are seeking similar remedies, including injunctive relief that would place a court-ordered moratorium on fracturing for the companies involved, compensation for damage to property or property values, and damages for the loss of the use and enjoyment of the property or their water sources.

In more than one of the cases, the plaintiffs allege not only physical damages, but medical damages as well, seeking costs for personal injury and for future health monitoring, which is a common claim among fracturing cases, as often the plaintiffs have yet to suffer health injuries, but allege that exposure to certain chemicals, including heavy metals such as manganese, may have latent consequences that do not reveal themselves for years.

Colorado, Louisiana, New York, Texas, and West Virginia, all states with burgeoning shale-mining operations, have themselves seen similar cases filed in recent years. In one Texas case, the plaintiffs claim that after the energy company commenced hydraulic fracturing near their property, their groundwater turned gray and became contaminated. Testing of the water allegedly revealed a number of metals, including aluminum, arsenic, barium, beryllium, calcium, chromium, cobalt, copper, iron, lead lithium, magnesium, manganese, nickel, potassium, sodium, strontium, titanium, vanadium, and zinc.

Like the plaintiffs in Pennsylvania, plaintiffs outside Pennsylvania also are primarily landowners. Their claims include:

• Negligence, for allegedly failing to properly case the well and thus prevent chemicals from seeping into their water.

• Negligence per se, if there is a state statute on point.

• Breach of contract or other similar allegations, if there is a lease.

Several cases allege trespass, based on the alleged intrusion of the polluted water into the plaintiffs' subsurface properties, or alternatively, based upon an unwarranted expansion of the oil or gas lessee's right to operate on the land—unwarranted because the leaking of chemicals is alleged to be outside of the scope of the oil or gas lease.

As of the writing of this article, none of the up-to 30 cases currently pending before US courts has reached final judgment; so it is difficult to estimate the viability of these lawsuits and their claims. Additionally, many of the cases are simply too early in the litigation process for defendants to seek an early dismissal or summary judgment requesting the judge dispose of certain claims.

Such motions, however, are pending in several courts. For instance, the primary defendant in one of the Pennsylvania cases recently brought a motion to dismiss the claims against it. The motion was denied for each claim save one for gross negligence, which is not a recognized cause of action in Pennsylvania.

Further, given that most cases are still in the early stages of discovery, plaintiffs have not had to identify their expert witnesses or the scientific evidence that will support their claims. This will be of paramount importance and may be another opportunity for the defendants to seek to have certain testimony or claims dismissed.

Of course, the problem for the industry is that even if the claims do not pan out, the cost to defend such lawsuits, in the aggregate, could be sizable.

Fig. 3 shows the new lawsuits filed in the US by year.

Government enforcement

Landowners, while the most plentiful plaintiffs, are not the only group seeking remedies for alleged damages caused by hydraulic fracturing. In what is becoming its own trend, government regulatory agencies and officers have commenced actions against the operators of fracturing ventures to enforce state interests and regulations.

In a separate action relating to the same operation as one of the privately filed Pennsylvania cases, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PDEP) initiated its own lawsuit against the natural gas company, on behalf of other plaintiffs whose water wells were allegedly contaminated by methane as a result of the company's nearby fracturing activities.

This action settled in December 2010, with the families represented by PDEP receiving $4.1 million in compensation, and the energy company agreeing to pay a $500,000 penalty to the agency.

While the settlement permitted the company to resume its hydraulic fracturing activities, it allowed the families who had joined the separate privately-financed action to maintain their suit.

Even more recently, on May 17, 2011, another energy company agreed to pay a fine of nearly $1 million to the PDEP for alleged regulatory violations that included contamination of water and a tank fire resulting from its fracturing operations.

Pennsylvania is not the only state authority to seek damages from energy companies that have violated state regulations. As on May 2, 2011, the Maryland Office of the Attorney General announced that it also intended to sue a hydraulic fracturing operation for injunctive relief and civil penalties, under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act and Clean Water Act, for spilling thousands of gallons of fracturing fluids into a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay.

In a move that could be emblematic of things to come, the federal government has become involved in the common-law regulation of hydraulic fracturing. In a separate case filed in federal court in Texas, EPA brought suit against a hydraulic fracturing company, alleging that the company released contaminants in two water wells that according to the EPA may present an imminent and substantial endangerment to the health of persons.

Arguing that state and local officials had failed in their duties to address the endangerment, EPA issued an Emergency Administrative Order (EAO) pursuant to the Safe Drinking Water Act to require the energy company to submit surveys of the water wells to EPA; conduct soil, gas, and air concentration analyses; and eliminate any gas flow to the affected aquifer.

The energy company-defendant disputes the EPA's findings and the validity of the emergency order. The US's aforementioned action seeks both injunctive relief to force the company to fulfill the requirements of the order, and the levy of a civil penalty for each day the company fails to comply.

The court recently stayed this lawsuit pending a decision by the Fifth Circuit in a parallel action filed against EPA by the energy company-defendant which argues that EPA violated its due process rights by issuing an EAO without a hearing or any proof of violation.

In another unrelated case, the question of whether an EAO violates due process rights is currently before the US Supreme Court.

Novel suits

In another recent development, which poses another potential hurdle for the shale natural gas industry, residents in Arkansas have filed five class action cases against energy companies which they claim jointly operate a number of hydraulic fracturing wells in Arkansas.

The class actions allege that the operation of these injection wells has caused several minor earthquakes in the area. Specifically, plaintiffs claim that since Sept. 10, 2010, the region, which is not normally prone to seismic activity, suffered 599 seismic events. The most significant was a 4.7 magnitude earthquake, which was supposedly the largest to hit the state in 35 years.

On Mar. 4, 2011, the Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission ordered a temporary shutdown of the wells to allow time to investigate the cause of the earthquakes. The energy companies named in the suits maintain that the earthquakes likely are coincidental and perfectly regular seismic activity. Importantly, in the week following the shutdown, earthquakes continued to occur, although not with the same frequency.

The class actions seek millions of dollars in damages for the loss of property values, emotional distress, and reimbursement for the cost of purchasing earthquake insurance. These are the first cases in the US to allege that hydraulic fracturing causes earthquakes.

Notably, on June 29, 2011, the named plaintiff, in one of the class actions, filed a voluntary motion to dismiss that action without prejudice because the action duplicated four other actions.

Regulatory responses

Another area of controversy involves the supposed exemption of hydraulic fracturing from federal regulation, and whether the process should be regulated by states or the federal government.

Specifically, the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), which was intended to protect wells, aquifers, and other sources of drinking water from contamination, as amended in 2005, defines an underground injection well as specifically to exclude hydraulic fracturing activities.4 In 2009, however, twin bills introduced in the US Senate and the House of Representatives attempted to close this loophole, collectively called the Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act, or FRAC Act.5

The FRAC Act would repeal the fracturing exemption from the Safe Drinking Water Act and would require the disclosure of chemical constituents, if not the chemical formulas, used in fracturing. Although the FRAC Act did not gain traction in Congress the first time it was introduced, it was reintroduced in the House and Senate on Mar. 15, 2011.

Regardless, in the absence of federal statutory authority, it is possible that EPA could intervene, as the agency already has once done in the case mentioned previously, thereby seizing regulatory authority over the industry via the use of emergency orders. This is not an ideal solution to the absence of proper fracturing regulation, as it could lead to patchwork enforcement and ad-hoc standards that are difficult to follow.

Despite proposed federal regulations, many states have instituted their own regulations of the fracturing process. First, and most commonly, states have begun enacting disclosure laws, requiring fracturing operators to list all of the chemicals they intend to use. Those states that create exemptions for companies that believe their fracturing compounds are trade secrets, such as Arkansas, nevertheless still require a disclosure of the chemical family name, and the volume of such chemicals that the company intends to use.

At this time, at least 28 states have adopted such laws, of varying complexity, and it is likely that more will soon follow.

In addition to disclosure laws, the SWDA bestows regulatory authority on the states to manage their own underground injection control programs; thus state agencies are administering at least some portions of the SWDA in their states. But as a response to the recent negative publicity of hydraulic fracturing, some states have taken an even more firm-handed approach.

One of the harshest responses has been in New York, possibly because New York residents are less accustomed to fracturing operations than those who reside in Texas or possibly because the population density places drilling apparatuses close to residential areas.

Either way, pursuant to an executive order by Gov. David Patterson in December 2010, the New York Department of Environmental Conservation was required to draft an environmental impact statement on fracturing, and no permits for high-volume wells may be issued until it is finished.

This EIS was recently released for public comment and is more than 1,000 pages long. This is simply the first step in a longer process before finalizing the EIS. Only then can the process of applying for permits begin, and even then, the first permits likely will be challenged by several special interest groups.

New York also has the most restrictive local ordinances. In Buffalo, for example, the local government adopted a ban on fracturing within its territory.

Other states have undertaken more unofficial efforts to frustrate the spread of hydraulic fracturing operations. In Maryland, the state indefinitely stopped authorizing permits in 2009, while it waits on the legislature to debate the merits of the process.

Additionally, though few have gone so far as Buffalo, many other municipalities also have flexed their regulatory might with respect to fracturing, enacting regulations to preclude nighttime operations, or imposing limits on noise, dust, and other nuisance creating activity.

Resource importance

Despite the challenges facing the natural gas industry on numerous fronts, the overwhelming importance of developing natural shale gas reserves cannot be overstated. Issues ranging from decreasing unemployment rates and increasing economic activity to helping the US become more energy independent and strengthening national security are tied to shale gas development.

Recently, several studies extolled the benefits of developing the vast reserves of US shale gas. It is hoped that these new studies will add to the dialogue that must continue on the exploration and the development of this important and abundant natural resource.

References

1. US Fossil Fuel Resources: Terminology, Reporting, and Summary, Congressional Research Service, Mar. 25, 2011, http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40872.pdf.

2. Shale Gas Gets Support from MPs in New Report, The British Parliament, May 23, 2011, http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/energy-and-climate-change-committee/news/new-report-shale-gas/.

3. Dillard, S.C., and Nicholson, B., Duke University Releases Study Reporting Methane Contamination in Areas of Natural Gas Extraction, The International Law Firm of Fulbright & Jaworski, May 11, 2011, http://www.fulbright.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=publications.detail&pub_id=4865&site_id=494&detail=yes.

4. Environmental Consequences of Fossil Fuel Exploration, The Energy Institute, University of Texas at Austin, May 9, 2011, http://energy.utexas.edu/research/fossil/.

5. Casey, R., and Schumer, C.S., 1215: Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act, 111th Congress, available at: http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=s111-1215.

The authors

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com